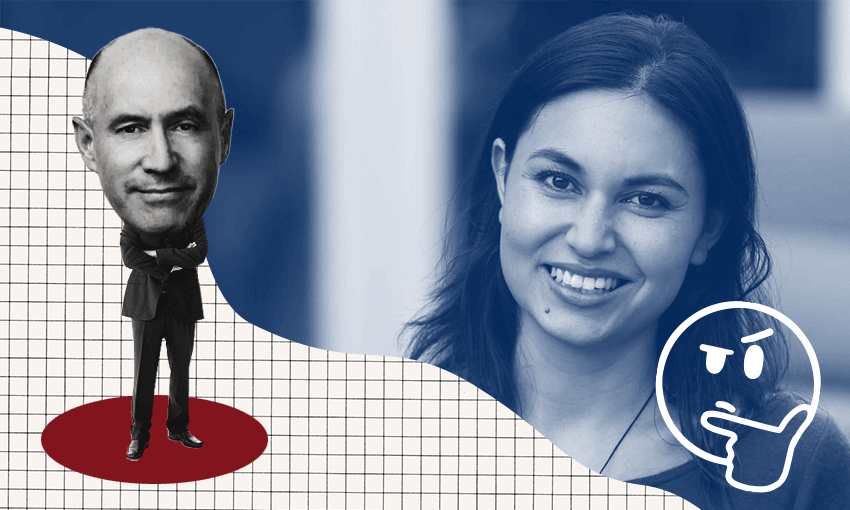

Amid the outcry over the blatant sexism of Henry’s ‘bit of fluff’ and ‘cleavage’ comments, the anti-Asian undertones of what he said has garnered less attention, writes Ruth Oy Har Agnew.

What surprises me most about the Simon Henry/Nadia Lim debacle is the way it has been so thoroughly covered in the media and captured the interest and indignation of New Zealanders across the country. While I’m grateful for the collective outrage from My Food Bag and Masterchef fans and the support shown for Nadia Lim, I can’t help but wonder why we haven’t had this reaction to other anti-Asian incidents in recent years. Where was the care and kindness for Sammy Zhu, a photographer assaulted in Ōtautahi in 2020 by a stranger in a racist response to Covid arriving on our shores? How did NCEA assessors decide it was appropriate to use the manifesto of someone who murdered a Chinese man in an external assessment, and why was it left to a year 13 student to challenge the decision (shout out to the magnificent Candace Chung for her amazing endeavour)? What action has been taken to address the rise in anti-Asian incidents since the start of the pandemic?

Of course, the attention garnered by Henry’s belittling may be due to his choice of target. Nadia Lim has to be one of the most likeable faces in local TV, sauteeing her way into our hearts with her dramatic Masterchef win, sashaying across the stage in Dancing With The Stars, and sorting dinner for middle class New Zealanders five days a week with her company My Food Bag.

All of which makes the smug self righteousness of Simon Henry’s comments even more audacious. He felt so comfortable sharing his anti-Asian sentiments that even one of our most successful and beloved New Zealanders could publicly be reduced to a racist, misogynist trope. If Lim, with her lengthy list of televised achievements, charitable endeavours and business forays is seen as a “bit of Eurasian fluff”, what hope is there for those of us with less impressive CVs to be seen as anything more than an ethnic trope? Would there have been such a groundswell of support if Lim had not been of mixed ethnic heritage?

At this point, I should mention my own ethnicity. My mother is sixth generation New Zealand-born Chinese, and my father is fifth generation New Zealand European of Scottish origin. My mother’s ancestors were beckoned here by the glimmer of gold, promising a better life. Perhaps my great-great-great grandfather, Choie Sew Hoy, would have had second thoughts about which country to settle in if he had known that over a century after his arrival, his descendants would still not be considered New Zealanders. Check the next census or hospital or educational institution’s ethnic identity form, and you’ll find options for NZ European Pākehā, but no tick box that acknowledges my mother’s cultural identity as a New Zealander of Chinese descent. The exclusion of any formal recognition of non-Europeans as “proper” New Zealanders citizens is an example of the casual and institutionalised racism that endows white-privileged men like Henry with the sense of safety and expected acceptance of such offensive comments. I’m not aiming to excuse his lazy leaning into preexisting ideas of the hypersexualisation of Asian women; I’m asking us all to acknowledge our role in creating a cultural acceptance of anti-Asian prejudice.

Jacinda Ardern’s condemnation of Henry’s comments seem to overlook the overt anti-Asian aspect of his slurs. Said Ardern: “Not only does that do a complete disservice to Nadia, I imagine it would be insulting to all women.” Clearly, all women matter, but by ignoring the racism inherent in Henry’s remark we fail to address the acceptance of casual anti-Asian racism that still exists in our country. Chinese in particular have been subject to more legislative prejudice than any other ethnic group. The Chinese Immigrants Act of 1881 introduced a Poll Tax of £10, later raised to £100 (about $14000 today), and the naturalisation of Chinese was stopped in 1908 and did not resume until 1952.

Throughout the late 19th century and first half of the 20th century, numerous organisations including the Anti-Chinese League, the White New Zealand League, the Anti-Asiatic League and the Anti-Chinese Association worked for further exclusion of Asian immigration, spreading a hatred and fear of “the Yellow Peril” to such an extent that in 1905, goldminer Joe Kum Yung was shot in the street by a Pākehā man who wanted to draw attention to his fiercely anti-Asian beliefs.

This century started promisingly for New Zealand Asians, with Helen Clark issuing a long overdue apology in 2001 for the poll tax and other discriminatory laws. However, we were still giving air to the myth of an “Asian Invasion”. A Labour politician blamed rising house prices on the number of “Chinese sounding names” he had seen, mocking Asian accents and stereotypes was still seen as a perfectly valid advertising technique (“splay and walk away”, “Monsoon Poon”), and a 2021 New Zealand Human Rights Commission survey found that four in 10 New Zealanders of Asian descent had experienced discrimination since the Covid outbreak.

So in a country with such strong roots in anti-Asian attitudes, it is disingenuous to ignore the role race plays in Henry’s casual dismissal of Lim. While I haven’t ever been called a “Eurasian piece of fluff” before, I cannot count the number of times men have tried to trap me in a tired trope of a hypersexualised Asian.

To those who feel a veneer of humour makes racism cute, let me be clear: speaking in a mock Asian accent will not entice me to “love you long time”, no, I don’t want you to white my wong, and I do not have sideways slanting genitalia (these are all genuine comments that have been made to me). Simon Henry is not alone in feeling comfortable and safe making targeted racist, sexist comments. So let’s use the discourse that has opened up around his comments as a catalyst for stamping out this acceptance of anti-Asian sentiment simmering under the surface in Aotearoa.