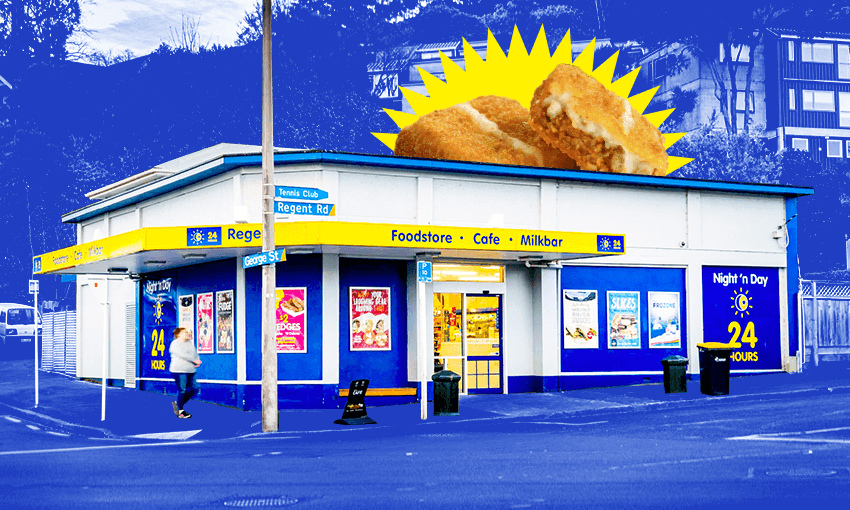

It’s long been the place to go for 3am pies and Powerades, but Night ’n Day has grown to become much more than just a late night snack spot. Chris Schulz investigates.

A little over a week ago, commerce and consumer affairs minister David Clark met with Matthew Lane, the general manager of Night ’n Day, in Dunedin. Together, the pair discussed the sky-high prices of groceries at supermarkets owned by the duopoly, an issue investigated by the Commerce Commission, regulated by the government, and talked about by literally everyone who lives in Aotearoa and eats food regularly.

When he emerged from that meeting, Clark issued a press release announcing he had just met with “the third biggest grocery provider” in Aotearoa.

Did you catch that?

Night ‘n Day, the collection of blue and yellow buildings dotted around the country and lit like hospital surgical rooms, the ones students stagger into to buy a pie and a Powerade at 3am because nothing else is open, has officially become New Zealand’s third biggest grocery provider.

At 32, Matthew Lane has gone from serving scarfies $2 lasagne toppers, to helming a nationwide network of Night ‘n Day stores, to campaigning on one of the most pressing issues of our time, meeting with the government and fronting media as he fights for a fairer deal for his “family” operation.

How’d that happen?

The following year, Denise and Andrew expanded the business to Invercargill and Christchurch, then began growing their family. Matthew, one of four children, was born in 1990, and has memories of long hours spent at the original Regent Road store, and of road trips as his parents expanded their empire. He remembers spending a lot of time, including late nights, at Regent Road. But he doesn’t remember stealing any chocolate bars off the shelf. “I was probably a bit young and a bit naive to be able to connect the dots at that age,” he says.

Realising they’d bitten off more than they could chew, Denise and Andrew settled on a franchise model, standardising the brand with separate owner-operators helming each outlet. Night ‘n Day stores proliferated around the South Island, becoming known for their cheap fast food offerings and unique menu: the Helova Cafe coffee brand, the stuffed sausages, and, of course, chicken cordon bleu and lasagne toppers.

They kept the Regent Road store, and Matthew Lane worked there throughout high school, then university, helping his friends get jobs there too. It had a well-stocked grocery range, including chilled goods and toiletries. But the store, located in the university precinct, became a favourite among a particular group of people, hankering for a certain type of food.

“Any student that’s gone to Otago University has very fond memories of us,” says Lane. Most, he says, would visit between the hours of midnight and 3am. “They grab a pie, lasagne, a Powerade for the next morning, and everything else in between.”

But something else happened when Night ‘n Day crossed the Cook Strait: it lost its wholesale grocery contract with Foodstuffs. That meant it could no longer buy grocery staples and offer them at competitive prices. “We had our Foodstuffs membership revoked,” confirms Lane. He doesn’t know if it was based on the North Island expansion, but believes the timing is no coincidence. “They were happy to have us for eight or 10 years prior.”

Instead, Night ‘n Day was forced to focus on offering good deals for its takeaway food. This is why Night ‘n Day’s coffees and lasagne toppers can cost just $2, but groceries like toilet paper and toothpaste are far more expensive than anywhere else. They have no wholesale supplier and can’t compete with the supermarket duopoly’s buying power. “My biggest frustration is that we can’t do that in a way that provides genuine value to the consumers,” says Lane.

Foodstuffs says the decision to exclude Night ‘n Day from its wholesale cooperative in 2011 was not related to its North Island expansion. Instead, it was due to breaches of the membership agreement, and a subsequent Commerce Commission investigation found it was a legitimate business decision. Foodstuffs declined to give any further details.

Lane, who became general manager in 2019, says even he wouldn’t buy his groceries from Night ‘n Day. “I wouldn’t come in and buy a tin of baked beans with prices as they currently stand,” he says. “For someone to come and get 15 items off our shelves in a basket, it’s unfair. That unfairness is being delivered to us by the majors. The staples are controlled by them.”

Night ‘n Day is well behind, he says. “It’s incomparable … because they’ve absorbed so much of the competition, so many of the brands in New Zealand over time, and the wholesale mechanism prevents anyone else getting established,” he says. “It reflects the difference between anyone else in New Zealand and the majors.”

Lane didn’t want to go up against the duopoly – by his own admission, he prefers to “fly under the radar”. He mentioned the business’s “family values” seven times during this interview, and listed several Night ‘n Day outlets that were owned by siblings and relatives. “We pride ourselves on putting our heads down and playing the hand we’re dealt with,” he says.

But he realised there was no one else with his experience capable of doing it. Online grocer Supie, which has also been outspoken, recently celebrated its first birthday. But Night ‘n Day stores have been around since 1984. “I can’t sit there and say it’s not working, and it’s not fair on consumers, it’s not fair on competitors, but not actually say anything to help the problem be solved,” says Lane.

So he met with the Commerce Commission, then Clark, then picked up the phone and spoke to The Spinoff for an hour, then patiently answered a barrage of text message queries, all while helping new franchise owners launch store numbers 56, in Christchurch, and 57, in Auckland.

Is it working? Several hours after The Spinoff put Lane’s allegations to Foodstuffs, the company issued a press release announcing it would open up its wholesale network to non-member retailers like Night ‘n Day. “There’s a lot to work through to make this offer work well for retailers who aren’t co-op members, but we’re building it with urgency,” said Chris Quin, Foodstuffs NZ managing director.

Would Night ‘n Day pivot away from lasagne toppers and back towards offering better grocery deals if they get access again to Foodstuffs’ wholesale network? “Absolutely,” says Lane. He’s been dreaming about doing that since 2010. “We have nothing to lose through doing that because we’ve been unable to build or maintain a market with the prices we have currently,” he says. “I’d happily sell baked beans out at cost because … we can’t get them at a cost-effective price.”

It’s not a cure, but Lane says it’s a start. “We’re in a position where the whole of New Zealand is held at ransom by two companies to purchase their essentials,” he says. He, along with his parents, who still contribute regularly, and his siblings, most of whom own franchises or work in the family company, don’t want to destroy those companies, they just wants the chance to compete. “We do what we do, we do it well, you get on with it,” he says. “We’re not going out to conquer the world.”

For more stories like this, sign up to The Spinoff’s new business newsletter Stocktake.