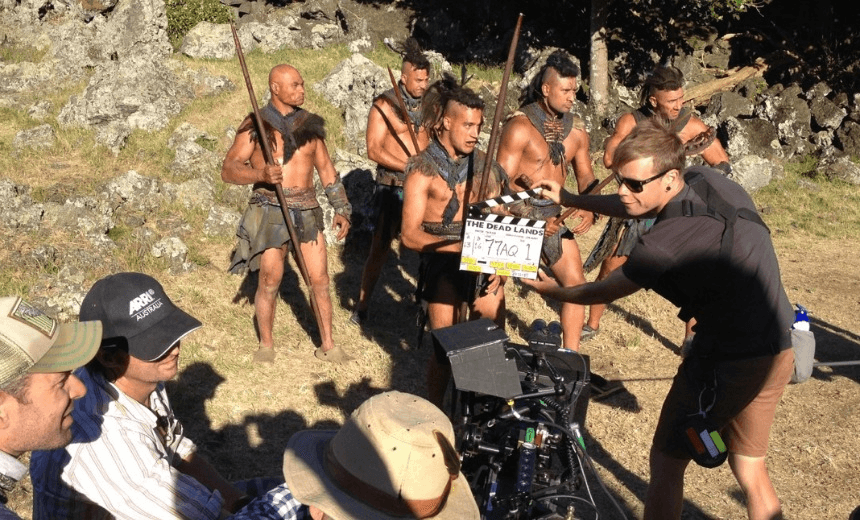

It’s been a good couple of years for Māori filmmakers. There’s been a solid stream of strong, popular films (Mt Zion, Boy, Maori Boy Genius) and several have torn it up overseas (Deadlands, What We Do In the Shadows). A new documentary, Hautoa Ma, interviews key filmmakers about the rise of Māori film. José Barbosa talks to the documentary’s director Libby Hakaraia.

If you go through even just a few of the people Libby interviewed for Hautoa Ma – Lee Tamihori, Taika Waititi, James Rolleston, Anisley Gardiner, Briar Grace-Smith, Chelsea Winstanley – there’s a very real chance of suffering an embolism just from conceptualising the heft of talent on show.

Hautoa Ma talks to just about all the current heavy hitters and, in the case of someone like Larry Parr, even those who’ve dropped out of public’s short term memory. Their collective experience and their thoughts around what exactly it means to be a Māori filmmaker leads to some interesting places. And some hard truths get highlighted: there’s only been two feature films directed by female Māori, the last one being Mauri by Merata Mita in 1988.

There are some huge structural beams laid right throughout the industry, and, fittingly, the documentary itself. Mentors like Don Selwyn, Merata Mita and Barry Barclay continue to infulence filmmakers today. Also, you can almost chart the evolution of production expertise in the Māori TV and film industry from some watershed productions like E Tipu E Rea and Once Were Warriors that employed, and taught key skills, a large group of current professionals.

I like how the documentary assumes knowledge of the subject from it’s audience – it’s not a primer Māori film. Was that the intention from the start?

In 52 minutes we couldn’t do a full reckoning. I though if we can touch on stuff, and pique people’s interest, the films are out there. For the older ones they’ll have to make a visit to the film archive, and they might be hooked for life.

It was slightly embarrassing for me to realise ‘oh look, there’s heaps and heaps out there.’

Oh look, I work in the industry and there are heaps of films that I saw when I was very young and can’t recall at all. There’s a truth to me having to sit down and watch about 52 films. You realise a lot of the early films had a lot to say. When you think about the challenges that the film makers faced, they’re pretty remarkable.

When you say they had a lot to say, what do you mean specifically?

Well they had a lot to say about New Zealand, about our society. I’m a child of the 70s and I remember listening to my father talk about his love of going to the movies in Otaki, but there being an unspoken rule that all the Māori kids sat upstairs and the non-Māori kids sat downstairs. That was the way it was. There was a sort of a segregation in some of the small towns around New Zealand between Māori and Pakeha. Some of those are themes that appear in the films, you can see the tension.

What’s the best example of that?

Broken English, Broken Barriers. That clearly talks about a young, mixed marriage couple. At the start of their relationship they’re in an urban environment and they feel very much like they can conquer the world. By the end of the film the societal view of their relationship has really worn them down. It’s actually a very sad film.

There are clearly points like that where people you’ve interviewed have referred to particular movies, and people as watershed moments for Māori film.

You have someone like Don Selwyn who came up through theatre. He was a great thespian study, and he could see that theatre was an entry point to Western culture. Because film was such a popular entertainment genre, Don Selwyn knew that’s where you could really leave a mark. A lot of Māori in both theatre, film and television will review to Don as being somebody that really inspired and mentored them. But he also saw the entertainment value of it and of a way of telling hard truths to people in an entertaining way.

Barry Barclay was a fighter, they all took on the gatekeepers of the day, those that didn’t want these films made. They just found a way to go around them, or over the top of them, or sometimes underneath them. And then of course you’ve got Merata Mita, her film Patu! looks at the Springbok Tour. That film is probably one of the greatest films that this country has ever seen, it captured the rise of Māori protest in that era and the anger. Without someone like Merata, we would not have properly seen how polarised we were at the time. That’s a really important piece in the canon of film making.

I thought it was interesting once the doco started getting into some of those nitty gritty questions around the discourse and debate around Māori culture and Māori film. Is it helpful to ask someone if they’re a Māori filmmaker, and what makes a film a Māori film?

Absolutely. We’re always asked that, and we ask it of ourselves as well. We might not be asking ourselves that in ten years time but right now it feels right. It is a political statement of a desire to tell our own stories and be recognised for telling our stories. What Māori filmmakers might be saying in the next five years, who knows? Whether you state it or not, you can’t take that away from somebody. I think it also is recognition of the way that Māori stories, like other indigenous stories, aren’t like what we see coming out of Hollywood or mainstream. Not all the time, and you can see some films where people go ‘is that really a Māori film?’ and we’re playing with genres.

Taika [Waititi] referred to it, he said there’s nothing really that new in filmmaking, once you’ve got the recipe it’s like baking a cake; you just bake a different cake. I’m really interested to see if that will hold true. The thing is, we’re not doing this in isolation. I spoke about those earlier films, where there was a sort of schism between Pakeha and Māori, but today we’re working together more. We see things in films that we recognise and I think it is taking Māori to make those films to tell those New Zealand stories.

Chelsea Winstanly points out there hasn’t been a Māori female director and writer of a feature film yet, and that sort of blew me away.

When Merata Mita directed her first feature film Mauri, that was 22 years ago. There’s not been one Māori women who’s been a director since then. Why does that fact exist? Why is that the case? We’re still fighting for stuff like that. It’s appalling. It’s not only about getting women to direct, but creating opportunities for people that are less funded. I’m having conversations with filmmakers in and around South and Central America where they’re only funders are the oil companies. These people are picking up cameras and making films and to get their stories out to the wider mainstream community, and all of the cinemas are owned by the oil companies. So it’s things like that where we kind of go ‘wow, really?” We’ve got more technology available now and we’re deciding as a group how to spin those out to the internet and festivals.

I thought it was interesting when Cliff Curtis was talking about his own kind of journey as an actor and a filmmaker, talking about how he started off being very protective of his culture and had to move past that. How did you respond to his discussion of that topic?

As he said, he kind of grew. Every new film is like creating a member of your family, giving birth, nurturing that member of the family. Cliff refers to his three W’s. The first is whakapapa, meaning how do I connect to the land and my people and how do I fit in? Then he refers to whānau. That’s the most important thing. Why is he making films? Who are the beneficiaries? Then he refers whenua – the land that nurtures him and connects him and gives him the ability to stand up in Hollywood. He’s played something like 42 different nationalities in his career so far, but that connection to his whenua, to Aotearoa gives him the strength that he needs.

I’ve had lots of conversations overseas with film buyers, film distributors, who constantly refer to the business of film. “The product. What’s the product?” That’s the truth of the business that we’re in – that it is a business. Films are very expensive, but they also leave a legacy, they advance a cultural need or express a political statement. When we refer to the whakapapa, and this is what the whole documentary relies on, people think that whakapapa is about looking back, it’s a family tree or it’s a geneology. We don’t see whakapapa as that, we see it as something you’re immersed in constantly. It’s not looking backwards, it’s actually being in this life, so this documentary was built on that premise – that we’re in the flow.

Hautoa Ma airs on Māori TV tonight at 8.30pm

This content, like all television coverage we do at The Spinoff, is brought to you thanks to the excellent folk at Lightbox. Do us and yourself a favour by clicking here to start a FREE 30 day trial of this truly wonderful service.