One of the most remarkable books ever written about crime, race, religious voodoo, and the New Zealand way of life and death is the Ngati Dread trilogy by journalist Angus Gillies. He self-published these three very strange and quite epic accounts of a five-year period (1985-1990) when there was a kind of Maori Rasta uprising in Ruatoria. They burned down houses, the police station, woolsheds, churches and even a marae. They kidnapped a cop. They were in a trance of prophecies, visions, and pot. On the morning of July 22, 1985, three local men climbed up a sacred hill….The following extract is from Footsteps of Fire, volume one of Gillies’ trilogy, and based on witness statements at the murder trial of Joe Nepe.

Jason Keelan and his friend Tuck Morice were having difficulty trying to dig out a blocked sump. They decided to head into Ruatoria to get a pick.

They stopped to buy milkshakes and some food, which they ate at a seat on the main street. Joe Nepe and Lance Kupenga approached. Joe asked Jason and Tuck if they wanted to help catch his horse at the beach at Tuparoa. Jason said yes, but Tuck said he’d meet them later. He wandered away, totally unaware of what he he’d just escaped.

Lance’s uncle Jacob turned up in his car. He had a bag full of stuff Lance had asked him to bring: some clothes, a bridle and his bankbook. Lance handed back the bridle and the bag, but took the clothes and the bankbook.

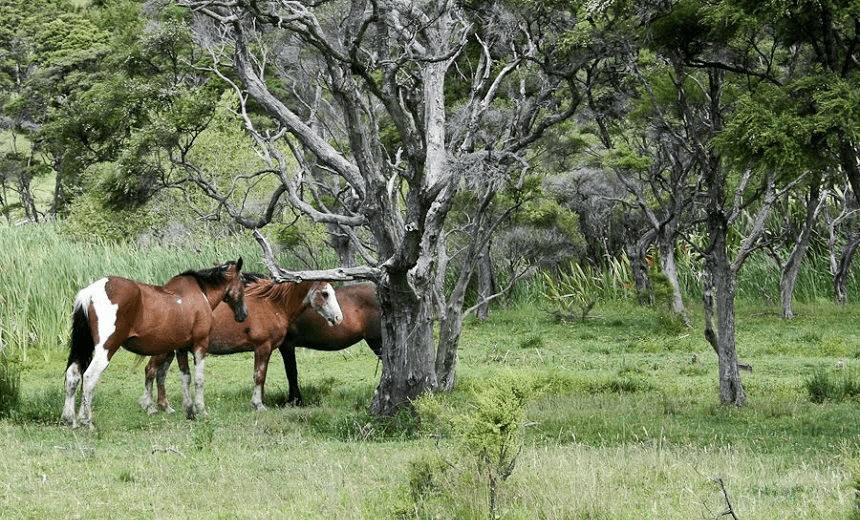

They set off. Lance was wearing jeans, gumboots and a red and black Swanndri. Joe was wearing jeans, a black coat, a hat and a red scarf, and carrying a broomstick without the broom on the end of it. A man gave them a lift to the end of the road, at Tuparoa Creek, near the beach. They walked past the local marae to a yard, where Joe thought he’d find his horse. It wasn’t there, but another horse was. They took it and set off for Whareponga and Whakaahu Hill.

Kupenga walked in front. Nepe and Keenan rode the horse, using Lance’s Swanndri as a saddle.

Joe told Jason that Johnny Too Bad had got into Lance. Jason understood what that meant. The Rastafarians had borrowed the term from the lyrics of reggae music: Johnny Too Bad was the devil.

*

They called at the home of Zula Rehutai, an old man who lived on the track they were taking up to Whakaahu. Jason noticed that, under his black coat, and around his waist, Joe was wearing a knife belt that held about four knives.

While they were riding the horse up the hill, Lance, still on foot, made a grab for the bridle. Joe reacted by breaking the broomstick over his head. Lance rubbed his head and asked, “What was that for?”

Joe got off the horse. As he did so, Lance’s Swanndri fell to the ground. Lance asked him to pick it up. Joe pointed the snapped broomstick and said, “Leave it there.”

Then he picked up an old piece of fence post from the ground and struck Lance on the heel of his gumboot with it.

They carried on through a gate. Joe again hit Lance about his gumboots and legs, telling him to get up the hill.

Joe said to Jason that Lance was “stink”. It was a term the Rastas used to describe someone who smelt like a rotting corpse. It meant they could smell death on them. Jason understood it to mean he was “rotten inside”, that he had Johnny Too Bad inside him. But he could smell nothing strange about Lance.

Joe threatened Lance: “Get back down to the river, or I’ll teach you not to play marbles with me when we get back up on the hill.”

Jason understood playing marbles to mean playing games with someone or, more specifically, mind-games.

They continued on, Jason on the horse, and Joe and Lance walking in front.

About two hours after they set off up the hill, they arrived at the hut on Whakaahu, known by the Rastas as “the bach” and used by the group when they wanted to get away from things. Joe told Lance to sit on a seat outside facing the ashes of an old fire. To the right was the hut, to the left an area with some scrim, propped up like a tent. Joe told Lance to look at a kete, hanging on a post to the right. Lance did as ordered. Joe went inside the hut.

Soon after he came out with a length of black cord, a blanket, and an axe with the Rasta colours of red, yellow and green taped to the handle. Joe slammed the axe into the seat, about a foot away and to the right of where Lance was sitting, hard enough for it to stick into the wood.

Kupenga started to cry. He pleaded, “Leave me alone!”

Joe grabbed Lance’s arms and tied his hands behind his back with the black cord. Lance didn’t struggle.

Jason was over by the tent, watching. He said nothing.

Joe told Lance that he was a toa, a warrior.

Lance told Joe that he was mad.

Nepe openly called him Johnny Too Bad. And Kupenga told him again, “You’re mad. You’re mad, Joe.”

He replied, “That’s not my name. I’m a warrior, Te Atau.”

“Leave me alone!”

“Who’s your name? Who’s your name?”

“My name is Lance.”

“Your name is Johnny Too Bad.”

*

Joe cut a hole in the blanket with one of his knives and put it over Lance’s head. He told him to walk up the hill. Lance walked on ahead and Joe followed. Jason was still standing by the tent. He told Joe he didn’t want to go up any further. He was scared; he’d never seen Joe act like this before.

Joe told him to come up so his tipuna could see him. Jason said he didn’t want to but obeyed, and walked towards him.

Lance picked his moment to escape. He freed his hands from the cord, kicked off his gumboots, took off the blanket and ran into the manuka bush.

Jason and Joe ran up to where Lance had left the cord, his gumboots and the blanket. “That’s how quick Johnny Too Bad is,” Joe said. He called out saying that if he came back everything would be all right. He said that if he came back he was Lance, but if he didn’t he was Johnny Too Bad. He called out like this several times. He told Jason to join in.

Ten minutes later, Lance emerged, limping. Joe told him to keep going up the hill.

They came to a waterfall where there were two pools. Joe ordered Jason to wash his hair in one pool at the waterfall, and his face and hands in the other. Joe did the same.

Kupenga was further up the hill. Nepe had told him to go up a goat track where his tipuna could see him.

By now it was about 2pm. They walked on up the steep, narrow track in single file, Lance first, then Joe, then Jason. No one spoke until eventually Joe announced they would pray.

He said they would face the sea so their tipuna could see them. They knelt, and chanted a karakia. It was a farewell prayer, known as a poroporoaki. Lance, in the karakia, was to depart in peace. They chanted for about 15 minutes.

When they finished, Joe walked about 20 metres away, sat down, and sharpened his axe.

The men were near two holes in the ground. One of them was known locally as “the bottomless pit”, where, it was said, bodies had been put for hundreds of years.

Joe stood up and said he wanted to have a talk with Lance. He tied Lance’s arms together with orange twine, and told him to lie on the ground. Then he used his knife to cut Lance’s jersey sleeves, the legs of his jeans, and to cut open his jersey from the neck to the middle of the back. He cut manuka branches and placed them over Lance’s body. He kicked him in the head.

He told Jason to go up the hill. Jason did as he was told. He was terrified.

Joe pointed with the axe at the two holes, one after the other, and told Lance, “Your head is going into that one and your body’s going into that one.”

Lance shouted at him, “Wairangi!” Meaning, mentally disturbed.

But Joe didn’t seem bothered. He was cool. He didn’t show anything. It was as if what he was doing was nothing.

Jason later described that he saw “Joe-Joe chopping with that axe at Lance”. It took two blows to sever the head.

Joe cried, “Utu! Utu!”

He kicked Lance’s head into one hole, and dragged his body over to the other, the “bottomless pit”. He threw the body down into the hole. Then he walked over to a tree and slammed the axe into it, leaving it embedded there.

It began raining.

Jason ran down the hill and waited. Joe followed in his own time.

They washed again, this time at a running stream. Jason washed his hands and splashed water on his chest and face. Joe washed the blood from his clothes and his boots.

Nothing was said as they walked down the hill to Whareponga Road.

The three volumes of Ngati Dread by Angus Gillies – Footsteps of Fire (2008), No Dreadlocks No Cry (2009), and Revelations (2011) – are available in selected bookstores and online. Tomorrow: an interview with the author.

Imagery courtesy of Panoramio user Abaconda.

The Spinoff Review of Books is brought to you by Unity Books.