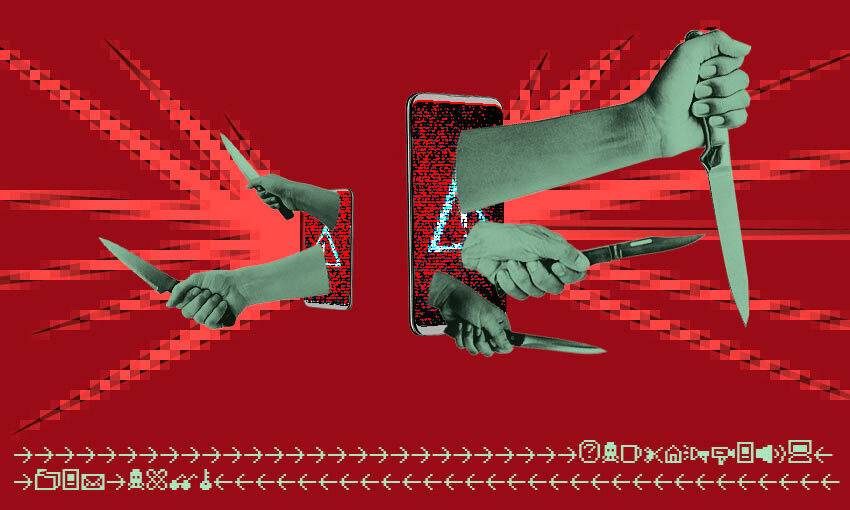

The rise of conspiracy theory and anti-vax sentiment has brought with it a rise in violent threats aimed at New Zealand media. Dylan Reeve writes for IRL.

I got my first death threat recently. It wasn’t a bullet in the letter box, or a horse’s head on my pillow. It wasn’t even an email. In fact, it wasn’t even a specific threat, certainly nothing I could report to the police. Instead it was a public reminder that, according to popular conspiracy beliefs, I would soon be rounded up, tried and executed for treason. It felt like a strange coming-of-age for someone writing about the Covid-denial, anti-vax and conspiracy rabbit holes that litter the internet.

From the very first article I wrote for The Spinoff about the more conspiracy-oriented side of the internet, I saw myself being incorporated into those same conspiracy theories, even briefly becoming the focal point for some of the obsessive personalities I wrote about. For example, in the comments on a long-since-deleted Facebook post, related to one of the people mentioned in the story, posters were asking questions like “who is he taking orders from?”

So I knew that, upon embarking on the IRL project, I would face similar attention if I was going to write about these corners of the internet. But still it was alarming to see posts referencing me in groups that frequently fantasise about executing perceived traitors – the politicians, bureaucrats, police and journalists that have supported the Covid-response, or maybe simply been in league with the Deep State.

In an unhealthy way I find the attention from these obsessive online personalities almost validating, but more reasonably I find it unnerving and threatening. I know I’m not remotely alone among my journalist colleagues in receiving this type of online attention, so I’m naturally curious about how they respond to this attention. Are they watching what’s said about them online? How do they react to threats they find or receive? I reached out to some colleagues who also find themselves the centre of attention within some of these conspiracy communities.

Newsroom journalist Marc Daalder has written extensively about New Zealand’s alt-right, conspiracy theory and Covid denial communities, and as such he has found himself a frequent target. Recently Daalder wrote about the growing threat of violence from the anti-vaccine community, and late last year about his own experience being on the receiving end of online threats after finding a detailed online missive about his impending murder.

Daalder’s article details a very specific threat to stab him to death in his sleep, posted on the anonymous online message board 4Chan. But the majority of the threats he sees now are vague and build upon the various conspiracy theory narratives about the stark future of military tribunals and execution that awaits journalists. Most of them are written about him, not to him. “One thing [the police] seem to think, which doesn’t make much sense to me to be honest, is that if someone hasn’t sent it to you, then it’s less of a threat. It’s less of a threat if they post about it with other people on a Telegram channel,” Daalder told me over the phone.

The threat that provoked me to write this article took the same form. My work was brought to the attention of thousands among the many Telegram groups of the local conspiracy community. The post was shared widely and various commenters weighed in. “Will just add this person’s name to the Crimes Against Humanities list,” posted “Amy” in one reply, apparently ensuring my inclusion in the upcoming tribunals. A post from “DeltaSierra46” was more direct: “I see dead man…” they replied along with an image of the Punisher skull on a background of flames.

There was nothing to suggest that Amy, DeltaSierra46 or any of the others who commented on or shared the posts about me were actually going to do me harm. But there was a clear sense that they would be happy to see me face capital punishment for my work. During interviews with vaccine-resistant New Zealanders, at least two subjects warned me that I should consider how I would “be held to account in future”, and that I should “remember what happened to the media at the Nuremberg”.

Journalists are constantly reminded by those steeped in online conspiracy rhetoric that we will, at some point, be rounded up alongside politicians and academics and placed on trial for our “treason” against the people of Aotearoa. The idea is drawn from QAnon and MAGA ideology out of the US, but has been swiftly rolled up into our local anti-vax conspiracy mythology.

The non-specific nature of these threats means that police generally aren’t able to take action. Daalder explains: “For them, having something like ‘I’ll be at your house at 4pm and kill you with a knife’ that’s a threat, but without all the specific details they don’t consider it [a threat]”. But he still makes reports about anything he feels is threatening. “I find it useful to make a record, even with something that’s anonymous.”

“Now I’m at a point where I don’t really care what the police say, but when this first started happening to me I’d only written about three articles on the far right in New Zealand,” Daalder recalls. “There was a mob baying for my blood and I definitely expected the police would do something. It was an incredibly alienating experience to have them not do anything and sort of gaslight me to say ‘there’s no threat to you’.”

I asked the police to comment on the issue but received no response.

Police reports don’t appeal to Stuff journalist Charlie Mitchell, who has also written a lot about Covid denial and vaccine resistance. “It would have to rise to a serious level for me to go down that path,” Mitchell told me by email, but he’s aware of his relative privilege (as am I) in ignoring these things. “I’m a 30-year-old able-bodied Pākehā man who rarely fears for my physical safety. I imagine there are many good reporters who won’t go anywhere near this issue because they know they’ll get abused or worse for doing so, and that’s a loss for everyone.”

Mitchell’s suspicion was supported by my struggle to find people to speak to about these experiences. Others I approached (including a number of women and people of colour) didn’t want to speak about the harassment and threats they received — they didn’t want to make it any worse by suggesting that the threats might be making any sort of impact on them.

One high-profile media figure I spoke to, who didn’t want to be identified due to the risk of inciting further attacks, told me they’d seen a steady increase in both volume and violent rhetoric in the threats they receive. But with so much of it anonymous and lacking threats of specific action, they felt there was little they could do.

Threats are nothing new to Mitchell (or most journalists) and he still remembers the first threat he received in response to his reporting: “I was a community reporter in North Canterbury and I’d done a few stories in quick succession about issues at a particular town — nothing especially controversial, just run of the mill community reporting stuff,” he recalls. But one story, about a local bridge, somehow struck a nerve. “There were multiple death threats against me on a community Facebook page.”

The nature and volume of the threats have changed since the pandemic, however. “The anti-vaccination stuff recently is truly wild. It’s on a whole other level,” Mitchell muses. “It’s one thing to get an angry email or a phone call from a farmer who’s just letting off some steam — that’s understandable, and I don’t hold it against them — but another to be told you and your colleagues are going to be executed for crimes against humanity because you’ve written favourably about a vaccine that’s been safely administered to billions of people during a pandemic.”

As someone who observes these online communities without taking part in them, it’s often easy for me to simply laugh at, or minimise, the claims and ideas I see posted. I don’t, for a minute, believe a Trump-commanded force of international soldiers is going to land in New Zealand to round up our politicians, journalists and academics, so I am not worried about those warnings. But there are people in those groups who do believe this stuff, and the concern lingers that some may decide they’ve waited long enough; that it’s time to get it started themselves — an idea known as stochastic terrorism.

A recent email from a high-profile New Zealand conspiracy theorist to many members of the media declared that journalists were terrorists. “Many of you everyday continue to act in ways that meet the legal definition of both criminals and terrorists under current NZ statutory law and common law,” it read. This is an idea that has been explicitly repeated many times by this person to an audience of thousands.

For Mitchell, the underlying threat in this rhetoric looms large: “It’s basically received wisdom now in some groups that vaccine mandates are equivalent to the worst atrocities of 20th-century dictators. You can justify pretty much anything if you think you’re preventing a literal holocaust,” he says.

“It’s bizarre and irrational, but that’s where some of them are coming from when they think about me and my colleagues, simply because they’ve become radicalised on the idea that a safe vaccine literally billions of people have taken is something sinister.”

Personally I want to ignore it, and mostly I do. However much I might annoy some in these communities, I’m still barely worth a mention to most. I’m not (so far?) on any of the “traitor” lists I’ve seen, and I have yet to see or receive anything that constitutes a direct threat. But the idea that some people are cheering for my execution (alongside my more prominent colleagues) remains alarming.

This piece was updated to include that the author had approached the police for comment.