The trial of the man accused of Grace Millane’s murder is unlike any other in New Zealand history, recounted in micro-beats, each one tweeted and push-notified. Anna Connell asks what it’s doing to justice.

It was a story that horrified New Zealand. In December last year, the news of the death of Grace Millane, a young woman and visitor to our country, left us shell-shocked. Now we, along with Millane’s family and friends, are processing the gruesome details of what is said to have happened as the trial of the man accused of killing her plays out in a very public way.

I have deliberately chosen not to seek out the trial coverage. It feels invasive and I’ve struggled to see the public good in the level of detail being reported. I’ve also been open to hearing arguments about why there might be some good in it.

Justice needs to be seen to be done. That is the fundamentally important role of the media within our justice system. The principle of open justice is one we should cling to and protect. Just as the fourth estate has a vital role to play in shining a light on the executive and legislative branches of government, it has the same role to play with the judiciary.

There’s also an argument that’s been put forward about the level of detail being important in order for us to understand what is said to have happened. I have some sympathy for this argument. Why should we get to shy away from these accounts of events?

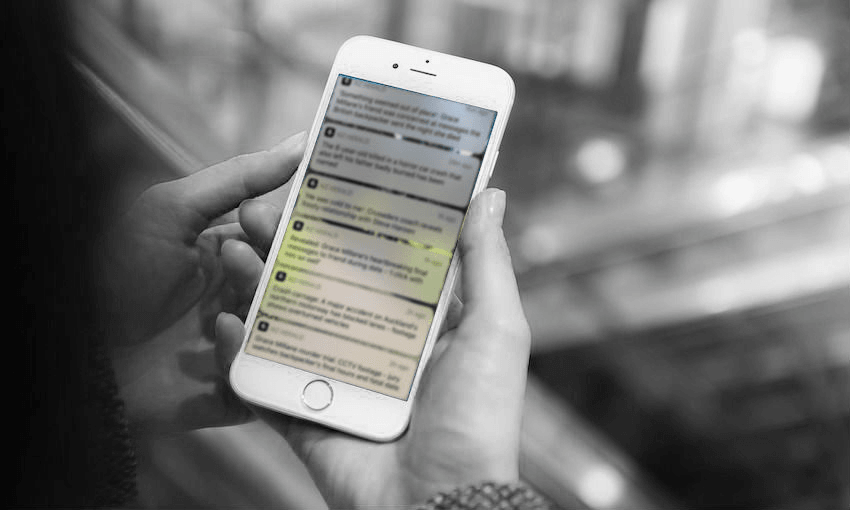

The issue for me ultimately lies in the way the trial coverage is being serialised, like an awful soap opera or true crime podcast. It’s not that the reporting is bad or beyond the realms of what is required to serve the principle of open justice. It’s that it feels as if it’s being pushed and packaged using every available technique in the media arsenal. The distribution of every new element as a separate piece of the digital news cycle is for me colouring the trial as much as the detail itself.

Snippets of CCTV footage shown in court has also been available for the public to watch on news sites. “Grace’s last moments,” blare the hourly headlines. To what end? What is the public good being served here? I’ve been told there’s a lot that’s not being reported – but what is being live blogged, live tweeted and circulated in frequent bulletins and push notifications is too much.

We place an enormous faith in the responsibility of a jury: to extricate themselves from the world around them; to focus on the facts and to deliver a verdict.

It sometimes feels an idea suspended in time. A time before push notifications and smartphones. A time before information could fly around the world with the touch of key. The judge can only ask the jury to avoid media and social media and the justice minister can only but plead with international media to observe our court’s rules.

Justice is an institution that is far more than the buildings, people and processes involved. It’s a noble idea and a set of principles. It is foundational, and it is, to a certain extent designed to be conducted in a vacuum, free of societal and political pressure. How does that work now when the pressure being applied is relentless and so liquid that it can seep in through the cracks? Is it an idea that’s too delicate to survive in this era? Is there some responsibility media need to take around the nature of its coverage? You can continue to ensure justice is seen to be done – but also that justice is able to be served.

Court reporting is a demanding and gruelling job. The pressures modern media face are also relentless and most of the time I understand that being first, fast and frequent is just the economics of the business these days. The problem is that both justice and media are vital institutions that have to coexist harmoniously, and it currently feels as if the pressure being placed on one of those institutions is contributing to the erosion of the other.

We, the public, might find it difficult to hear and see this trial play out the way it is. We might be weary from the rapid-fire notifications and forensic detail popping up without warning on our phones. We might be right about it being gratuitous and bemoan the news media, but we’ll endure. Will justice?