The Single Object is a series exploring our material culture, examining the meaning and influence of the objects that surround us in everyday life. In the fifth part of the series James Dann explores Christchurch’s ties to the heroic age of Antarctic exploration, and embarks on his own journey of discovery in pursuit of a pair of skis.

After shivering through another winter in a poorly insulated house, many Cantabrians won’t want to be reminded of Christchurch’s proximity to the Antarctic. The city’s location, its port, and later its airport, have made it an ideal base for many of the expeditions that have set off to explore the southern continent, and Christchurch has built a strong connection to the frozen south.

Christchurch Airport is an important base for the US “Operation Deep Freeze”, and close to these hangars is the International Antarctic Centre, a tourist attraction for those who enjoy being needlessly cold. The Antarctic Heritage Trust is based in Christchurch, working to preserve some of the early huts of the likes of Robert Falcon Scott, Ernest Shackleton and Carstens Borchgrevink, while the Canterbury Museum boasts “the largest and most diverse collection of Antarctic memorabilia and photographic images in the world”, including a cache associated with Captain Scott’s final, fatal expedition in 1910-1912.

There are many reminders of the Scott expedition around Christchurch. A marble statue of the explorer, carved by his wife Kathleen, was unveiled in 1917. It was toppled in the earthquakes, snapping off at the ankles, but has now been restored and sits back on its plinth. He’s got a pole, but no skis.

While the early 20th century was the age of exploration, it was also a time of discovery and innovation. After the lights were first switched on in Reefton in 1888, New Zealanders began to flock to electricity like moths to a flame. By 1910 it was clear electricity was here to stay – and the state would play a significant role in its development.

At the time power was supplied to Christchurch from a generator attached to an incinerator, fuelled by garbage (this was on the corner of Armagh and Manchester Streets, where the Margaret Mahy Playground now is). As demand continued to outstrip supply, the government began work on the Lake Coleridge hydro-electric scheme in 1912, which was completed in 1914. Four years later is where the skis come in.

At the end of June 1918, there was a massive snowstorm in Canterbury. Early in the morning of 1 July, as still happens during snowstorms (and earthquakes), power was cut off to the city. Both the north and south transmission lines to Lake Coleridge, the city’s main source of electricity, had failed.

Coleridge is around 100km inland from Christchurch, in the shadow of Mt Hutt. With snow as thick as a metre deep on the plains, and getting deeper in the foothills around the lake, there was no way for the electricity department to get to the power station and attempt to restart the connection to the city. As one of the engineers, Edward Hitchcock, recalled many years later in Mark Alexander’s Christchurch, a City of Light, the long delay in restoring power was not “due so much to the damage to the wires, poles, and transformers, but to the fact that telephone communications between Christchurch and Lake Coleridge were completely disrupted”.

The team at the power station might have been able to get it up and running again – but they couldn’t risk putting power into the lines in case there were people still working on them, who would have been electrocuted. It was easy enough to get through to Hororata, which was still 40km away, but travel beyond that was nigh on impossible. None of the cars or trucks that were available (this was 1918, remember) could travel through snow that deep. As they headed into the third day without power, it was clear that the snow wasn’t going anywhere – and neither was anyone from the electricity department.

Lawrence Birks, the chief government electrical engineer in the city, was desperate to get through to the station. He had sent cars and motorbikes with no success. Men on horses hadn’t been able to get through. Birks tried to get in touch with some farmers in the South Canterbury town of Fairlie, who were in possession of a couple of early motorised sleds that Scott had taken with him on the Terra Nova expedition. They even entertained the idea of attaching an aeroplane engine to a sled, hoping it might glide across the snow, but nothing came of it.

Then a young employee of the Public Works Department, Boris Daniel, suggested that he could ski to the power station. Daniel had learnt to cross-country ski when he was a child. He was born near Minsk, in what was then the Russian Empire but is now Belarus, in 1889. After a stint in Siberia, then in Queensland (which he found too hot), he had made his way to Christchurch.

His offer to ski cross-country to Coleridge was an interesting one, but there was a problem: no one had any skis. While the Ruapehu Ski Club had formed in 1913, the first club in the South Island was still more than a decade away. Indeed, skiing was such a novel activity that newspaper reports from around this time gave guidance on how to pronounce the word (‘she’, apparently).

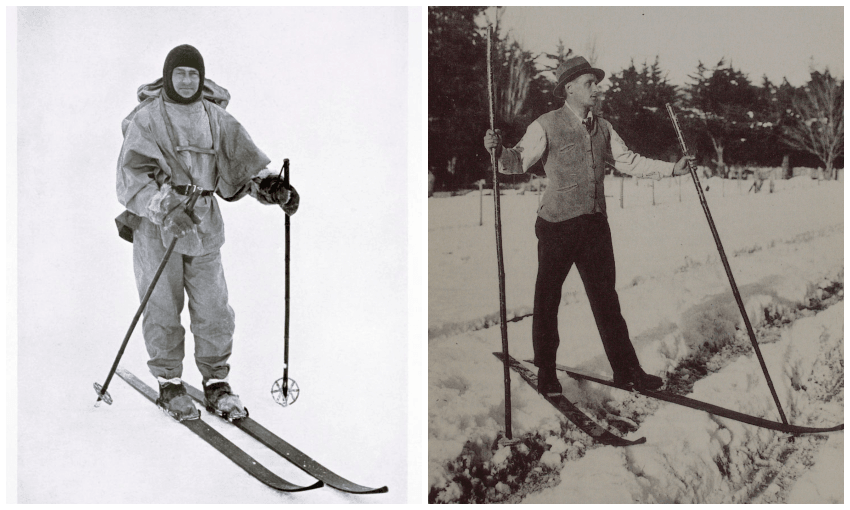

As all of Birks’ other attempts had failed, he put the call out for a pair of skis for Daniel, and eventually some were sourced from a rather special owner. Because of Christchurch’s role in Antarctic exploration, there were a few souvenirs from the expeditions kept in the city’s museum. So on 3 July, Daniel made his way up to Hororata with a pair of Captain Robert Falcon Scott’s skis.

It had been seven years since Daniel had last been on a pair of skis, so his first day was reasonably gentle. He was also under very strict instructions to be careful with the skis, given their historic provenance. To avoid clipping the skis with the poles, he had to hold his arms wide apart as he propelled himself along.

He made his way to a farmstead, where he slept the night on a pile of horse covers. The next morning he set off early, catching up to a pair who had been dispatched by horse days previously, but weren’t making much progress. When Daniel caught up to them, they gave him their message for the powerhouse, and a flask of whisky, before turning around and heading back towards Hororata.

The Russian continued on and the terrain started getting steeper. Eventually he spotted three black figures in the snow ahead. As he got closer, he found that it was a Mr Blackwood, the manager of the power station, and two of his colleagues, who were coming in the other direction from the lake. Daniel gave them the two messages he was carrying, which instructed them when it would be safe to reconnect the power lines. The group all then headed back towards Hororata, staying the night at a farm station along the way. When they woke the next morning to finish their journey, they could hear the buzz of the power lines above them. Their message had got through.

When Daniel reached Hororata on 5 July, the whole town came out to welcome him. Birks had driven up from Christchurch, along with a newspaper reporter. Despite being exhausted, and having done some damage to his ankle, Daniel was happy to pose for a photograph. In it, he stands proudly on the skis, wearing a tie and a waistcoat, with his arms still outstretched so his poles didn’t hit the precious artefacts.

The caption states that the skis were from the Canterbury Museum, so I got in touch with them to ask if they would permit me to come in and see them, and maybe take a photograph. They seemed a bit confused. I gave them an overview of the story, and they checked their records: nope, they don’t have any of Scott’s skis, and even if they did, they doubt that they would have lent out such a precious item.

I began to question the whole story – ‘man borrows Captain Scott’s skis to restore power to the city’ sounds too good to be true, so maybe it was? The Canterbury Museum has an excellent collection of important objects from these expeditions, including from Scott’s. They have multiple pairs of skis, but all are from other members of the Terra Nova party, rather than Scott himself. Another pair of skis from the Scott party is in the collection of the Lyttelton Museum, which is still awaiting a post-quake rebuild. The other large collection in Christchurch is the Antarctic Heritage Trust, but again, no skis. I’ve also checked with Te Papa, Otago and Auckland, with no luck.

I dove into PapersPast – a remarkable resource for historical information – and to my relief, there were a number of contemporary news reports about Daniel’s brave journey. He definitely was the hero who skied up to the lake and back. So my next question was whether he did it on Scott’s skis. This was also supported by the newspapers. Apart from incorrectly stating that the skis had come from the Canterbury Museum, the rest of the story could be verified. The owner of the skis wasn’t the Museum, but instead a man named JJ Kinsey.

Joseph James Kinsey was born in Kent, and moved to New Zealand in 1880, setting up a shipping company that played a key role in providing supplies for the early Antarctic expeditions. He provisioned Shackleton’s two expeditions – the Nimrod that left Lyttelton in 1908 and the disastrous Endurance expedition that left in 1914. He became acquainted with both Scott and Shackleton, and entertained them at his houses in Christchurch. He was knighted for his services to Antarctic exploration, but his real reward was the acquisition of artefacts from these expeditions. It was Kinsey who supplied Scott’s skis to Daniel in 1918, and on his death, bequeathed his archives to the Alexander Turnbull Library. But they were not a part of that library’s collection – and my search for the lost skis was again thwarted.

Finally, when I was digging through Papers Past for more information about Boris Daniel, looking for another hint as to where the skis might be, I came across an interesting nugget. Two people left Hororata by ski on 3 July, 1918: Daniel in the morning, and then around noon, a Finn named Mr W Sandelin, who took a more northerly route, following along a second power line to the station.

Sandelin was also an electrical engineer from the Department of Public Works, and so as he went along, he repaired any faults he could find in the line. He also set off on a pair of historic skis, previously owned and used by Ernest Shackleton.

These skis were acquired by a Mr J.H. Blackwell, the mayor of the small town of Kaiapoi, about 15 minutes north of Christchurch. Blackwell had seen the request for skis, and knew there was a pair in his town. The set of Shackleton’s skis was at the Kaiapoi Working Men’s Club, which was happy to lend them for this endeavour.

The Kaiapoi Working Men’s Club still exists, though, like many clubs of this type, has dropped the “working men’s” bit from its name. I rang them in the hope they might know something about this pair of skis from 100 years ago. When I heard the receptionist call out “do we still have those old skis?” to someone across the room, I knew I was on to something. She didn’t know much about them, only that they were old, and that they were on the wall above the door in one of the bars. The next day my expedition took me to Kaiapoi, the skis, albeit a different set, within my grasp.

On a sunny spring day, on the mouth of the Waimakariri River, the little town of Kaiapoi looks a picture. It was hit badly by the quakes, but has seen a bit of a boom since, with many people from the city moving to the town and then commuting back into Christchurch for work. Historically, one of the biggest employers in the town was the Kaiapoi Woollen Mills, which, apart from making distinctive blankets that are now very collectable, also produced high-quality warm garments that were used on the Antarctic expeditions. Many of the workers from the mill would have been members of the Working Men’s Club, which holds a prime position in the centre of town, overlooking the river.

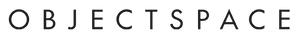

I head for the Robert Falcon Scott Bar in the now abbreviated Kaiapoi Club and there they are. Arranged in a cross above one of the fire exits are a set of skis, with a plaque and a portrait next to them. But as I get closer, I realise they aren’t from Shackleton’s expedition – they’re from Scott’s! The plaque mentions they were used on the Discovery expedition, while the portrait is of Scott on the Terra Nova voyage. It certainly explains why the club has a bar named after Scott, but these skis raise as many questions as they answer.

I still don’t think they’re the skis I am looking for. By comparing them with the picture I have of Daniel on Scott’s skis, I’m pretty confident these are different – they’re sharper and skinnier than the skis Daniel borrowed. The newspaper clipping said the Kaiapoi Working Men’s Club had a pair of Shackleton’s skis, and yet I found a pair from one of Scott’s expeditions. I think it’s more likely the newspaper report confused Scott and Shackleton than there being two pairs of historic skis in the one working men’s club.

So how did the skis end up here? The plaque states that they were presented to the club by the officers and crew of the Discovery, though it doesn’t state when. The town does have a connection to Scott – a man named Charles Lammas, a Brit who was part of the Terra Nova voyage. He went down to the Antarctic in 1910, but wasn’t part of the party who stayed on the ice. After the ship returned to Lyttelton, he moved to Kaiapoi, and the records show that he joined the Working Men’s Club in December of 1913.

When I started off on my expedition, I wanted to reveal the extraordinary story of Boris Daniel and the skis that he had travelled on to restore power to Christchurch 100 years ago. While I wasn’t able to find the object at the centre of this tale, I did find plenty of other pieces of Christchurch’s rich Antarctic history. Like the great explorer Captain Scott, I too have set a course into unexplored territories, been faced with unexpected challenges, and not fulfilled the ultimate goals I set for myself – but unlike Scott, I managed to stay nice and warm while doing it.