More liveable, more sustainable, more equitable: is Aotearoa on the verge of an urban planning revolution?

This content was created in paid partnership with WSP New Zealand.

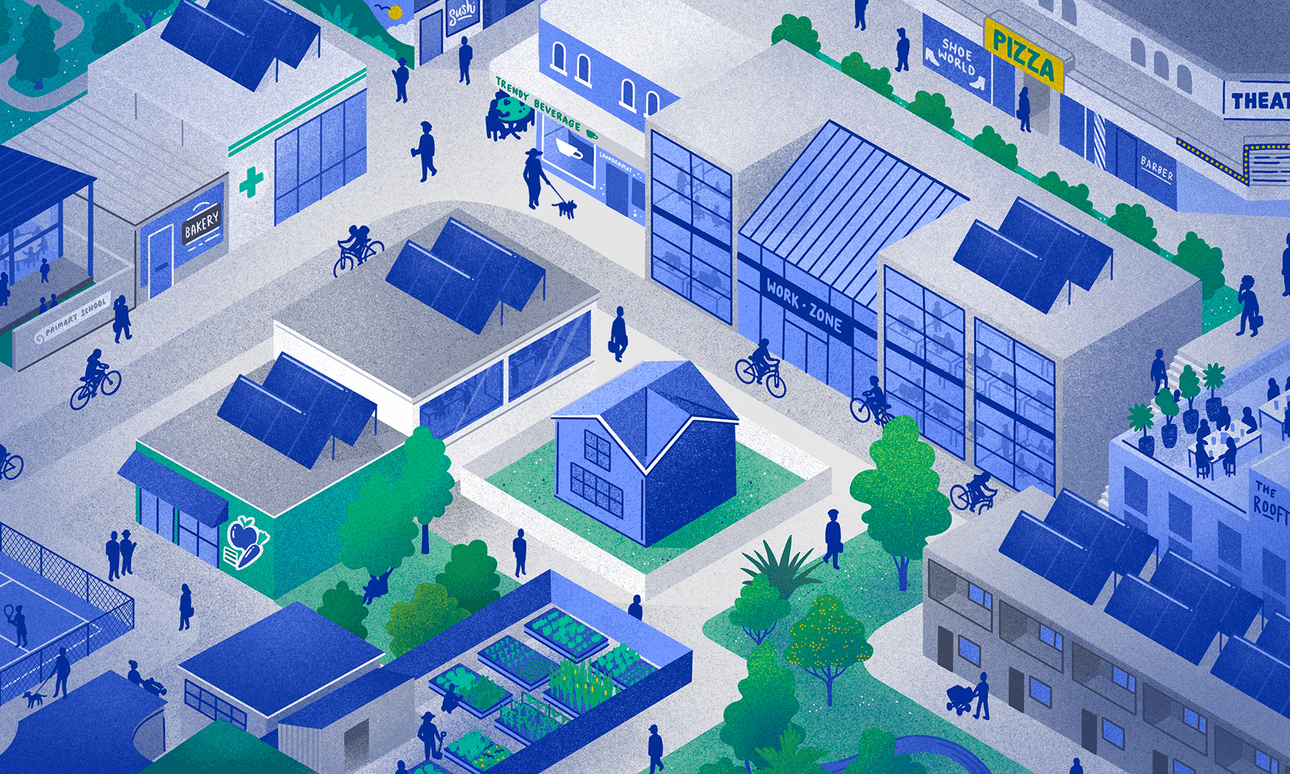

Imagine a future where every person living in urban New Zealand could access all their needs within a 15 or 20-minute walk. Where local schools, supermarkets, affordable housing, entertainment and work were just a stone’s throw away, and easily accessible, fast public transport meant all the rest was easy to get to without a car.

For thousands of people living in our main centres right now, that idea probably seems like a faraway dream. Heavy traffic and seemingly endless roadworks make moving around our cities a lot harder, promises of improved public transport are slow to be realised and there continues to be a severe lack of affordable housing nationwide, particularly in the central areas where people are more likely to walk to work.

That may be starting to change. Courtenay Northcott, kaihoahoa whenua/landscape architect and urban design lead at WSP, says the Covid-19 pandemic – and in particular the associated rise of work-from-home – encouraged urban planners and councils to rethink how cities should work in the 21st century.

“The world is starting to consider climate change and sustainability and associated things like carbon emissions. These all tie into the 20-minute city concept, which has been gaining traction in recent years. But Covid really amplified things because we were all at home and wanted to be able to access our amenities and our necessities easily, and some people couldn’t do that.”

WSP is a company that helps governments and local decision makers create innovative, sustainable infrastructure and engineering solutions. The Future Ready concept was created by WSP in the UK, and is now a global strategic planning and design methodology which uses evidence and insights on key trends to help decision makers understand the implications of their planning choices. These implications now include sustainability, which has become one of the main drivers for urban redesign over the last decade.

Northcott wants New Zealand to be the next place that adopts the Future Ready model. She thinks the foundations are already there for building cities that will cater to the demographic trends of the future. But the answer isn’t simply creating better urban infrastructure.

“Twenty-minute cities are about economic growth, development, infrastructure, and that all has to be tied together by behaviour change. If people aren’t buying into what we’re doing – or they refuse to use the cycle lanes or public transport – then it’s never going to work.”

Holly Walker is deputy director and WSP fellow at the Helen Clark Foundation, a public policy think tank based at AUT. She’s writing a report on how the returning diaspora can contribute to the future of our cities, and how we build an environment that encourages them to want to stay here.

It’s not just the built environment that will help to convince returning New Zealanders to make this their permanent home, says Walker – it’s about our unique cultural environment, too.

“How well are we welcoming back returning New Zealanders? How welcome do we make new migrants feel? Do we have employment opportunities for people who are coming home?”

After living overseas, Walker says a lot of people are excited to return home, but the realities of coming back are often less thrilling.

“There is surprise at the cost of living, the cost of housing, the lack of great transport infrastructure, the amount of cars on the street, the lack of public transport. It’s hard when people are used to living in a major city where public transport is accessible because it’s simply not like that here and hasn’t moved on in the time that they’ve been away.”

In WSP’s 2021 Future Ready 20-min City in Aotearoa report, cities like Portland in the US, and Sydney and Melbourne across the Tasman are singled out for their efforts to make their urban environments less car-dependent. Portland’s governing body’s plan to make the city more accessible is on a tight time frame: by 2030 they want 90% of their population to be able to access all basic daily non-work needs within an easy bike ride or walk, and have prioritised low-income, under-served communities for targeted improvements.

In Sydney, the plan for a 30-minute metropolitan region designed around three Sydney “cities” has a target of 2050, with the key Parramatta light rail project expected to be complete in two years. In Melbourne the “20-minute neighbourhood” idea is shaping infrastructure planning, with local government working towards a goal that by 2050 most of Melburnians’ daily needs will be met within a 20-min return walk from home.

Walker says the physical layout of many New Zealand cities means not everything that has worked overseas will be possible here, so there’s no blueprint we can borrow in full. Building cycleways in Wellington’s hilliest suburbs may not do much to encourage novice riders, for example. But there’s still much that can be done, she says.

“We need to work within the natural physical layout of some of our cities and towns. Some lend themselves more naturally to [the 20-minute city] than others, but that’s great – let’s start where some of it is already there, where we can ramp it up quickly and really demonstrate the results.”

Without demonstrating those results, progress won’t occur at a rate necessary to keep up with skyrocketing urban population growth.

“By 2048, nearly half of New Zealand’s population (44%) is projected to live in just three cities alone: Auckland, Hamilton and Tauranga,” says the WSP Future Ready report. As well as this huge growth in numbers, there are going to be large changes in our city’s demographic makeup.

“Our Māori and Asian populations are going to pass the one million mark in the next 10 years or so; we’ll have over 500,000 Pasifika people,” says Walker.

While the idea of a 20-minute city in New Zealand may still seem decades away from being realised, Northcott is optimistic about some of the changes already underway in our biggest cities. Christchurch has been leading the way in redesigning its transport infrastructure with a focus on cycleways, and the City Rail Link in Auckland, set to be completed in 2024, will have a huge impact on the way Aucklanders and visitors use the city and its resources.

“I think once these things start falling into place and linking up they’ll be really great… Wellington is interesting, I lived there for about seven years and the CBD is a perfect example of a walkable, cycleable city.”

The 20-minute city model has the potential to completely change the way we live, work and experience our communities. As our cities continue to sprawl outwards, the test is whether those on the outer edges are being serviced the same as those in the centre. WSP’s goal is to convince our local and central governments that without plans in place to help our cities get there fast, we’ll be left behind.

“We need better support from central government for councils to make those changes and more of a strong central government policy mandate to say ‘This is what has to happen, now go and make changes’, rather than leaving it up to councils to do it all,” says Walker.

Making moves that could make Aotearoa a future world-leader in sustainable infrastructure and liveability can happen now. It’s up to the people sitting on our local and central governments to help those possibilities become a reality. For Northcott, Future Ready means more than just creating new infrastructure. It’s about the people whose lives will improve because of it.

“We don’t just think about the road, we think about the cyclists, the pedestrians, the trees, the biodiversity – we want to actually make a difference to future generations.”