When it comes to the cost of building roads, we’re asking the wrong questions.

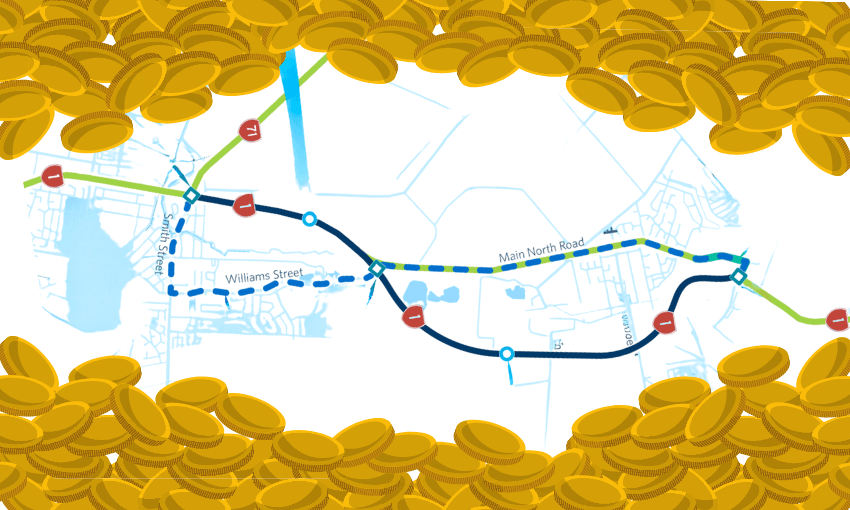

A proposal to toll the Woodend Bypass, a new highway extension north of Christchurch, has riled up Cantabrians more than the idea of giving the Crusaders a less racist name.

Waimakariri mayor Dan Gordon is absolutely steaming. “For a resident in Pegasus or Ravenswood, at $2.50 per return trip, that’s around $1,300 a year for the average workday commuter – a bill many families simply can’t afford,” he said in a statement. Christchurch Central MP Duncan Webb is fuming. “You shouldn’t have to pay every time you drive to work,” he wrote on social media. On his Mailchimp poll, more than 80% of participants didn’t support tolling the road.

This debate has played out several times before: Transmission Gully, Penlink, Manawatū-Tararua and Ōtaki to north of Levin. Whenever governments suggest tolls, it gets messy. People get really mad when you ask them to pay for something they’re used to getting for free, and politicians tend to roll over pretty easily once the Facebook comments on the local community page turn against them.

The politics of road tolls are tricky. The current government wants more tolls – possibly even on existing roads – because it encourages a user-pays system that reduces the burden on taxpayers. But conservative voters, especially in more car-dependent rural areas, absolutely hate them. Left-wing governments have some affection for tolls as a way to encourage behaviour change or divert more funding to other transport modes. But their voters get up in arms about equity – road tolls take a bigger chunk out of household budgets for poorer families than rich ones.

Then, there’s the geography problem: any time a toll gets proposed on a particular highway, locals in that area feel unfairly targeted and argue that another region is getting a better deal. In the case of the Woodend Bypass, the popular comparison has been Transmission Gully, which NZTA considered tolling but ultimately decided against.

Before introducing any toll, the Land Transport Management Act requires the minister to consider the “level of community support for the proposed tolling scheme in the relevant region” – which is kind of redundant. No one likes paying tolls. If Coca-Cola asked people whether their products should be free or cost money, what do you think the answer would be?

Ideally, toll roads should have a free-to-use alternative route, so people aren’t forced to pay if they don’t want to. But that brings its own problems. Kaiapoi North School principal Jason Miles has raised concerns about “rat-running” – people speeding through the alternative route past his school, making local roads more dangerous. For Transmission Gully, NZTA wanted to shift traffic away from the existing coastal route, so it decided that any decision that encouraged more people to use that route would defeat the point of building the new highway.

That raises the question: if significant numbers of drivers would rather use an objectively worse road to avoid paying a couple of bucks, then maybe the case for spending hundreds of millions of dollars on a new highway isn’t as strong as it seems.

Te Waihanga’s draft National Infrastructure Plan sets out a fundamental problem: New Zealand is in the top 10% of OECD spending on infrastructure, but in the bottom 10% for the “bang for buck” we get from our infrastructure spending. The government’s response to this has been to investigate new funding models – PPPs, overseas investment, and tolling – but it overlooks a far more fundamental issue: we’re really bad at choosing which roads to build.

Waka Kotahi NZTA evaluates all proposed transport projects using a benefit-cost ratio, or BCR, which estimates how much economic benefit is generated for every dollar spent. In simple terms: is it good value for money? The BCR isn’t a perfect measure, but it’s the best tool available. The strongest projects can reach double-digit ratios, while the weakest fall below 1, meaning the costs outweigh the benefits.

However, starting with the Roads of National Significance programme launch in 2009, successive governments have pumped enormous amounts of money into projects with extraordinarily low BCRs. A business case in 2018 estimated Ōtaki to north of Levin had a BCR of between 0.22 and 0.37 (and that’s before costs blew out by more than double). Transmission Gully had an initial BCR of 0.6 (ditto). The Woodend Bypass scores a 0.95.

So why do these projects keep getting funded if they’re such money pits? Politics. A town grumbles about the state of its roads, politicians rush to promise a fix, and parties ignore the BCR in favour of chasing votes. (This has historically been more associated with National, but Labour is also guilty.) However, there is little evidence to suggest this is an effective tactic. Even at the last election, where potholes were a major talking point, transport infrastructure failed to break the top 10 most important issues in the Ipsos Issues Monitor survey. Promising a billion-dollar highway has a terrible ROI in terms of winning votes.

Now, let’s talk about who pays for these new roads. New highways are mostly funded through NZTA revenues – road user charges, fuel taxes and the like. But increasingly, they’re drawing on other taxpayer funds – Crown appropriations and loans, largely due to stimulus spending under the previous Labour government. For local roads, owned and operated by councils, NZTA only covers about half of the cost – the rest is lumped on ratepayers (who are also taxpayers).

Tolling would add another revenue source – but its impact is often overstated. On Transmission Gully, tolls were estimated to raise $3.5m a year, which would have barely put a dent in the final price tag of $1.25bn. But while they might not cover construction, tolling could be an important way to fund renewals. As Strong Towns founder Charles Marohn put it when discussing his recent visit to Aotearoa, “Maintenance has to come first. Because every new pipe, road and sidewalk isn’t just an investment; it’s a long-term liability. An intergenerational promise and obligation.”

Maintenance is the overlooked and unsexy part of funding new roads, but it’s incredibly important. And when discussing how to pay for it, it’s important to ask: what does the damage? The answer, overwhelmingly, is trucks. Approximately 80% of all road maintenance costs in New Zealand are the result of the damage caused by trucks. According to some estimates, one truck does the equivalent damage to a road of 800 to 1000 cars.

This is a spiralling problem. As rail has declined due to underfunding, freight has shifted to roads, leading to heavier trucking volumes, more road damage and higher costs to taxpayers.

Every motorist and taxpayer is subsidising the trucking industry, footing the bill for the damage they cause. On the Woodend Bypass, cars would pay $2.50 while trucks pay just $5 at each of the two proposed polling points. So before we wring our hands over commuters, let’s ask the real question: are trucks paying anywhere near their fair share?