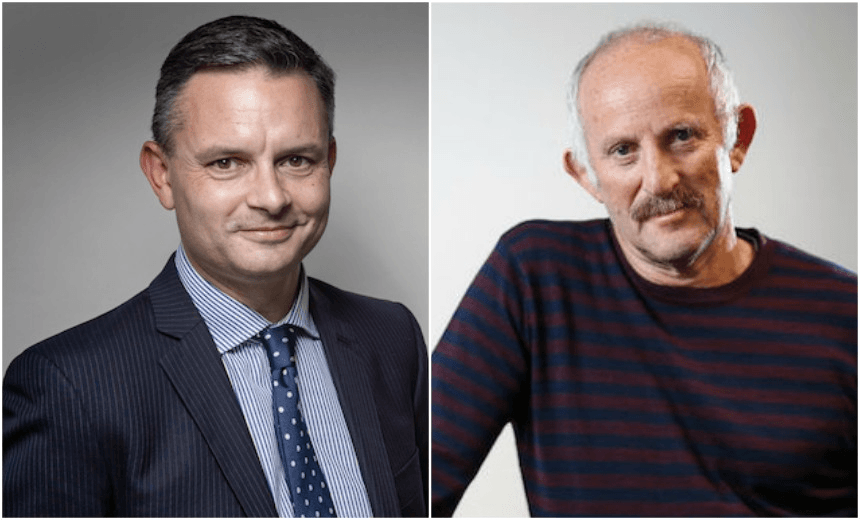

The speculation about a Greens-National coalition is futile given the tribalism of New Zealand politics, writes former National cabinet minister Wayne Mapp. Instead, he wonders if a revitalised TOP can become a second, centrist Green party.

All the discussion about a possible National/Green coalition reminded me just how much political parties are tribes. They are not just a group of individuals with similar political views. They also typically share a common social construct. This is why a National/Green coalition is highly unlikely – not just now, but also in the future.

It might seem facile to say that most members of political parties have similar backgrounds. But it is an important truth. It may provide some guide as to what might happen in the next few weeks.

In National: business people, farmers and professionals serving business predominate among their members of parliament. In Labour: the university common room, teachers and state servants figure strongly. Of course there always exceptions in the two major parties. National usually has some academics, just as Labour always has some business people. The Greens are younger and are typically urban professionals, or have come from an activist background. New Zealand First resembles National, though perhaps without the connection to larger international businesses.

It is not just political parties that build around particular relationships, so do many of us. I recall as an MP a constituent saying to me she knew no one who was going to vote Labour. More recently, in respect of my article as to why the vote was flowing away from Jacinda Ardern, a number of commenters said that could not possibly be true; they knew no-one who was going to vote National.

Of course many of us have much wider networks among both friends and family. On my wife’s side, at one stage she had three relatives who were MPs in three different parties. Of course one of those relatives was me. In reality, even those who think they know no one who voted for the “opposition” will likely be surprised at their relatives and friends actual voting patterns. We are a small enough, and healthy enough society to have diverse connections.

All this plays into the relevance of the current flurry of articles and discussion about the prospects of a National/Green coalition. It is highly unlikely to take place, certainly not in this electoral cycle. The network of Green activists and supporters come from a very different place to National. Many are ex-Alliance or from parties even further to the left. The thought of a coalition with National, no matter what the quality of the deal, is anathema. On that basis the Greens are permanently wedded to Labour, with all the attendant disadvantages of only being able to go one way.

Guy Salmon has mooted the possibility of TOP being able to be a more centrist Green party. Is this actually feasible?

Actually yes, at least if there is a three or six year plan. Modern politics has given credence to the flamboyant and eccentric leader, and Gareth Morgan certainly fits that bill. Perhaps he might need to tone down some of his musings, but there is no doubt that he is the driving force of TOP.

In 2017 the Green Party got 5.9% of the vote and TOP 2.2%, a total of 8.1%, substantially less than the peak of 11% which the Greens have achieved in the past. It is at least arguable there is space for two ‘green’ parties in parliament, both around 5 to 6% of the vote. One would be the current “red” Greens permanently wedded to the left. The other, built around TOP, would be more centrist party primarily focused on the environment, able to deal with either the left or right of politics. Neither would be wholly environmental. Their main players have interests wider than that. However, this is all an issue for the future.

The main event in this election is New Zealand First. A conservative party of provincial New Zealand. It is not a right party, but rather a populist party drawing support from both left and right.

Which way will it go? Are there any indicators? The New Zealand First MPs are more like National MPs, but they are not National. A number have Labour origins.

Perhaps the most important factor is that National got 46% compared to Labour’s 36%. It is a big margin. Even the combination of Labour and the Greens is still 5% shy of National. That is why this election does not seem like a change election to me. Change elections are like 1999 and 2008 when the main opposition party clearly beats the main governing party.

National will argue that a National – New Zealand First government with a prime minister having gained electoral authority is the easiest option. It will be able to present a new agenda to the people of New Zealand. And in 2020 be judged on the success of that programme. That agenda will include a much bigger role for the regions, with more focus on infrastructure and lifting living standards, especially for those currently on the margins.

However, the reality is that Labour, New Zealand First and the Greens can also command a majority in Parliament. It is possible for them to form a government. A government that will also have a major role in the regions. But likely with more social and environmental spending than the National New Zealand First alternative.

Winston will play this close. It will not be easy for the public to discern the most influential factors on his decision until after the fact.

In the meantime we can all speculate.