The quarrel over immigration and the free-trade agreement is more than just a matter of opinion.

That Winston Peters and his New Zealand First Party are opposing the free-trade agreement with India is no surprise. They similarly opposed the free-trade agreement with China 18 years ago. Then, as now, Peters was foreign minister. Then, as now, he said it was a bad deal for New Zealand. Then, as now, he invoked an “agree to disagree” provision in the governing arrangement.

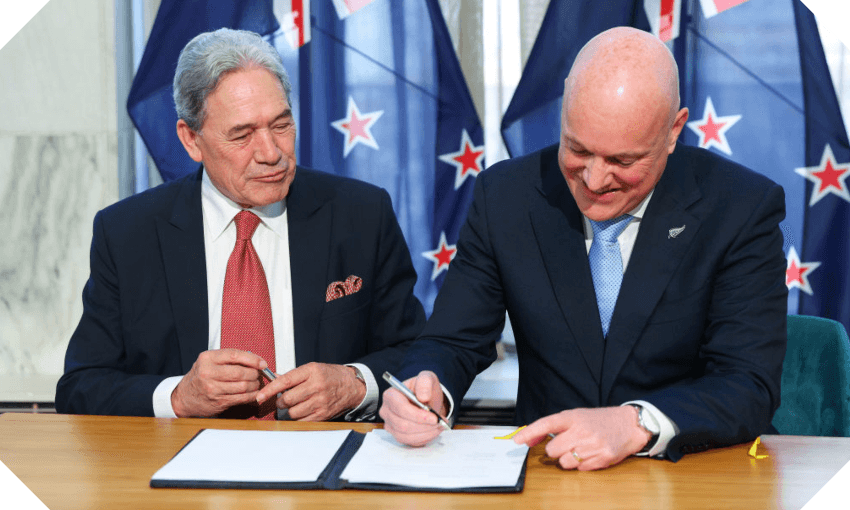

Christopher Luxon, who is seeking Labour support to get the FTA across the line in his coalition partner’s stead, has counselled that all we’re seeing today is “mature disagreement” in MMP politics. He can live with Peters railing at a “rush job” and “low-quality deal”. He can wave away with a grimace the plain contradiction of Peters’ insistence that this is not a normal trade agreement but “substantially an immigration deal” while his trade minister, Todd McClay, says there is “nothing about immigration in this agreement”.

But, in parts at least, this is not only about opinion, and emphasis, and rhetoric, but also about fact. Luxon says Peters’ claims are “wrong”, “plain wrong” and “just wrong”. Peters says the prime minister is wrong to say he’s wrong. Who is right?

The bones of contention

Peters – who has geared up for an election year with an increased focus on immigration, including warnings of “mass immigration” – greeted the announcement of the FTA three days before Christmas by stating that, regrettably, they must oppose a deal that “gives too much away, especially on immigration”. He added: “By creating a new employment visa specifically for Indian citizens, it is likely to generate far greater interest in Indian migration to New Zealand – at a time when we have a very tight labour market.”

Peters then put a figure on it: the deal would pave the way, he said, for as many as 20,000 Indian nationals to be in New Zealand under the Temporary Entry Employment visa at one time. The deal provided for up to 5,000 of these visas, and successful applicants would be able to bring their spouse and children.

By late last month, he was telling reporters, “the truth is not being told to the public”. His advice: “Go and dissect what it means. It means we could have tens of thousands of people getting here of right and building up employment opportunities in this country for themselves and taking those opportunities away from New Zealanders.”

Christopher Luxon said, “He’s wrong.”

What does the deal itself say?

In seeking to discern who’s right about the wrongness, a helpful reference would indeed be the literal words in the trade deal. Alas, that’s still locked in legal quarantine, as lawyers pore over the words, and may be there for many weeks yet.

A briefing note from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade avoids any explicit reference to immigration, but does contain a short section headed “Temporary movement of people”, spanning temporary visa provisions, a working holiday programme and post-study visas.

On the temporary employment entry visas – the bit about which Peters is most agitated – the ministry note says the trade agreement “includes simplified entry arrangements for Indian service providers and professionals for short periods of stay”. That would amount to 1,667 temporary employment entry visas a year, but only for occupations in which New Zealand has a skills shortage, “such as certain ICT fields, engineering, and specialised health services, as well as certain iconic Indian professions such as Ayush (Indian traditional medicine) practitioners, music teachers, chefs and yoga instructors”.

The three-year visas are capped so that no more than 5,000 can be in use at any one time. And a sea change it is not. “This represents less than 6% of the average number of total skilled visas issued each year by New Zealand.”

The working holiday scheme, meanwhile, would provide up to 1,000 places for Indians aged 18 to 30, while the deal “codifies the right for Indian students to work for up to 20 hours a week (within current policy of up to 25 hours)”. And, finally, students graduating from a New Zealand tertiary institution who meet the criteria “are eligible for a post study work visa, ranging from two years for Bachelors, up to four years for PhDs”.

The government response

A fortnight ago, Todd McClay pushed back at Peters’ suggestion that 20,000 Indian nationals might be welcomed to New Zealand under the FTA, telling a select committee that the agreement offered no rights on bringing family members. Peters countered by pointing out that such rights were already provided under New Zealand law for anyone with a work visa of a year or longer. “So, given a standard family size of two parents and two children, this means 20,000 people in New Zealand at any one time under the new visa which has been created exclusively for Indian citizens.” He noted, too, that “the Indian government has itself described the FTA as providing ‘unprecedented mobility opportunities for Indian professionals [and] students’”.

Warming to his theme, Peters concluded. “Judging by both the FTA, and how it’s being promoted in India by the Indian government, we’re likely to see much more migration from India in the years ahead. Neither New Zealand First, nor the Indian government, are ‘wrong’ about that.”

The trade minister did offer something of a subsequent clarification. He told media that, on bringing family along, he had simply meant the deal afforded no extra privileges to those already permitted under the rules. He emphasised, further, that the deal would not oblige any government to keep those settings as they are.

A binding cap?

Another objection that has been raised by Peters concerns locking in provisions for students from India. “We also hold concerns that the deal ties the hands of future New Zealand governments,” he said. “The proposals around the work rights for Indian students, both when they study and after they graduate, would constrain the ability of future governments to make policy changes in response to changing labour market conditions.”

Just a few hours after Peters issued his statement on January 29, McClay responded to this in the house. He had a caucus colleague ask him questions about the trade deal, including: “Does the FTA with India give rights of migration or immigration to Indian nationals?” “No, it categorically does not,” McClay told Peters – correction, sorry, told parliament. He reiterated that temporary workers were admitted “to meet skill shortages in our economy”.

As for the student visa cap and future governments, McClay said: “It does not remove a cap on the number of students who can come to New Zealand, because there is not a cap. But it also does not restrict future governments from creating a cap should they wish to. The FTA does not restrict the ability for future and current governments to modify work visas or student policies or settings.”

The deal does, however, proscribe changes that would cap Indian student visa numbers in a way that disadvantaged them in comparison with other countries – that is, New Zealand could only introduce a cap on Indian student visas if it introduced a cap on international student visas across the board.

Speaking yesterday on Herald Now, McClay explained it this way: “If you look at a trade agreement, what it often does say or indicate is you can’t discriminate against one party versus other parties around the world. But New Zealand doesn’t do that. If you look at all of our policies, including students, wherever a government has wanted to have some sort of control on numbers, they put in place immigration rules … There is nothing in the agreement that says a current or future government can’t alter those settings.”

What does Labour reckon?

They’ve been enjoying, needless to say, observing the crossfire – in their war of wrongs, the prime minister and the foreign minister had “basically been calling each other liars”, was the assessment of Chris Hipkins.

On the points of contention, the Labour leader, who has not read the full text of the FTA, was cleaving towards camp Winston. He told RNZ yesterday: “By my reading of the deal, what Winston Peters has said about [the cap] is correct, and what Todd McLay said about that is not correct, which is there is no provision in the deal for New Zealand to impose a cap on the number of international students who could come into New Zealand under the deal … So if we reach a point where there’s a lot of international students coming into the country and all taking up their new right that the deal enshrines for them, to be able to work while they’re studying as well, that could have a distortionary effect on New Zealand’s labour market, and the deal potentially offers no remedy for that.”

He said Labour was still weighing up whether to support the agreement. “We are trying to be the mature, responsible ones here, and that means fully understanding the implications of the deal that the government have signed us up to.”

And so we’re left with semantics, and waiting for the lawyers to parse them. In an election year, especially, nature abhors a political vacuum, and for Peters, the explanation that the text of the deal is stuck in legal pipes doesn’t cut it. “Something,” he told Newstalk ZB, before reaching for the W-word, “is going awfully wrong here.”

This article has been updated to correct the language around the TEE visa quantum vis-a-vis overall skilled visas issued, to reflect a correction made to the MFat document.