The major parties will soon talk less about each other, and more about each other’s putative coalition partners.

If MMP elections are a cocktail bar, 2023 is likely to offer one of the simplest menus New Zealand has seen. Pick your drink: National or Labour. If you want it stronger, choose a shot of Act or Green.

There are other variables, to be sure. Te Pāti Māori could end up with the shaker in its hands; another party could gatecrash the place. But – for now at least – the electoral moonshine of New Zealand First is off the shelf, and the options are sharpening in focus.

It’s untypical for Act and the Greens to both be sitting comfortably above the 5% threshold in polls at this point in an electoral cycle. And it’s highly unlikely either National or Labour will take power at the end of next year without negotiating a formal coalition with a partner that is big enough to command senior roles and a bunch of seats around the cabinet table.

Against this backdrop David Seymour rolled up to Act’s conference yesterday and laid out his “plan for the first 100 days of government”. Top of the party leader’s list was a Royal Commission of Inquiry into New Zealand’s Covid response. Whatever the quibbles about the form, scope and composition of an inquiry, it’s clearly a good and necessary idea. Clever politics on the part of Act to make it a headline demand, perhaps, but I’d be surprised if every party doesn’t go into the election promising something similar, albeit without Seymour’s gonzo demand for a “glasnost” probe.

The pricklier pledge was as much about National as it was Labour. “We won’t allow National to lazily roll over Labour’s policies like it has in governments gone by,” said Seymour. “National will need to learn how to share with a larger and more powerful coalition partner than it’s had before.”

The 100-day list will hardly alarm National partisans. Repeal of three waters, of the Māori Health authority, of the offshore oil and gas ban, of the so-called “ute tax” and of the highest tax bracket are all National policy already. They, too, oppose fair pay agreements and like the idea of charter schools – Christopher Luxon was lavishing praise on them in London just the other day. As for “Stop the Public Interest Journalism Fund”, that will be pretty much done and dusted by the election and there’s little sense that Labour, let alone National, has any appetite to renew it.

But it will nevertheless give National strategists pause. Act has essentially set the agenda, enumerated the question lines to be put to Luxon in the days and weeks to come. David Seymour has demanded that the Zero Carbon Act is repealed within 100 days, Mr Luxon. Are you on board? Do you also want to bin Oranga Tamariki’s requirement to prioritise whānau for tamariki Māori? And so it will go, through to the election. You do need to learn how to share.

National’s approach in the last two or three months has evinced the energy of a small-target-strategy – encouraged by Labor’s success in the Australian election, they’ve sought to avoid the opposition dangers of barking at every passing car, taking positions on all and sundry, making grand pledges and declamations. Instead, with the electorate focused more than anything on mortgages, rents, bills and the price of cheese, you don’t stray far from the economy. You don’t, for example, want your backbench MPs posting love hearts all over Facebook at a US Supreme Court ruling.

While you can stare down a caucus member with an appeal to discipline, unity and the greater good of the party, however, you can’t control the statements of a future coalition partner. It’s all very well carefully installing a small target if someone else is bouncing dart boards around the place.

This is not exclusive to the right side of the spectrum. When the Green Party stages its AGM in a fortnight, almost every promise and ambition will be seized on by National to weld to the Labour platform. The only question, really, is whether Labour will start warning in foreboding tones about the dangers of an Act-National government before National does the same about Green-Labour.

A campaign in which rivals take aim at each other’s outriggers is not, of course, new. Bottom lines and rulings-out are stock elements of a proportional system. In 2013, John Key attacked the Labour-Green alternative as a “devil-beast”. While Key’s National managed repeatedly to govern without forming a coalition (but with ministers outside cabinet), that didn’t stop his opponents cautioning that the coat-tails of Epsom could hold him to ransom.

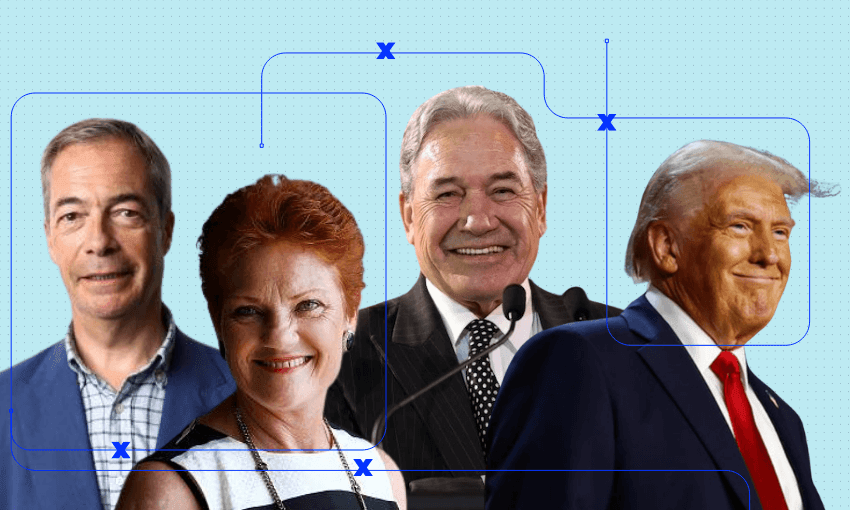

One of the reasons the dynamic suddenly feels more pronounced is the absence – for now, certainly – of New Zealand First, an acquired taste, but one ready for mixing with any drink. And because the idea of coalitions barely figured in 2020. That election very obviously was freakish, a majority government returned by an exceptional response to an exceptional crisis amplified by an opposition party in an exceptional spiral of self-destruction.

In the months ahead, as long as the polling remains in roughly similar territory, there may be an incentive on both sides to spike their rivals’ guns. After leading Labour to a crushing defeat in 2014, David Cunliffe said he regretted snubbing an offer from the Greens in the campaign to work together. In 2016, the parties did precisely that, issuing a public memorandum on “working together” for the election the next year.

The pact had limited force – as witnessed in the leadup to Metiria Turei’s resignation – but it will nevertheless be on the minds of all four parties today. Because it’s clear already that if you vote Labour or if you vote Green you’re voting for a blend of the two; and it's the same for National and Act. Given that, the argument goes, why not quietly coordinate your efforts? At the very least, strive not to furnish your opponents with political ammunition. The counterpoint: you've got to demonstrate conviction, be impassioned, crisp and different. Who wants to vote for an appendage?

David Seymour was attempting to navigate all that yesterday. It was for the most part a pledge to pump yellow steroids into a blue body. He didn’t bother with the phony electoral rhetoric of pretending Act could be “the government”. He said, “Act is on track to play a powerful role in the next government,” and polling shows that’s no hyperbole. It's a remarkable truth that none of New Zealand's nine MMP elections has landed Act or the Greens in a formal governing coalition with permanent places around the cabinet table. One of them is almost sure to break that drought next year, and that knowledge will profoundly inform the months to come.

Follow our politics podcast Gone By Lunchtime on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or your favourite podcast provider.