A Wellington school’s use of a ‘seclusion room’ to isolate autistic children has been dismissed by officials as a sorry aberration. But the school cell speaks to a much bigger problem with special education in New Zealand, says Giovanni Tiso, the father of two children with autism.

There are few things more distressing and painful than the injury caused to those who cannot speak. The parents of Baxter Mansfield, a child with autism who attends Miramar Central School in Wellington, made the point very eloquently to John Campbell yesterday.

“He’s non-verbal so he can’t tell us what is going on. He has different ways of communicating. There is no way he could say, ‘Mum, I was locked in a room today.’ And that’s our biggest fear, for a child like that who is so vulnerable, we need to trust who we leave to care for him.”

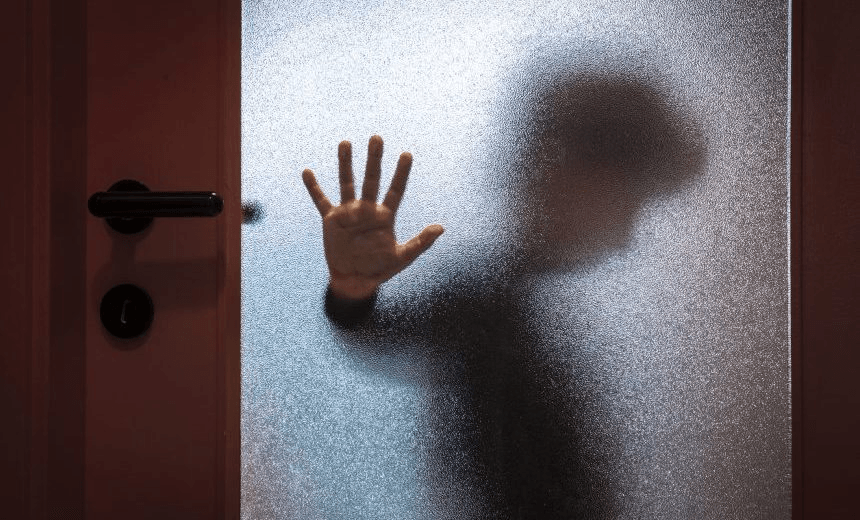

The existence of the seclusion room in the school’s special unit was revealed over the weekend in the New Zealand Herald by Kirsty Johnston, whose work in exposing stories of abuse of disabled people has been exemplary. Baxter’s parents didn’t know about the room, nor did almost any of the parents of the 10 children who have been routinely locked inside the dark, cupboard-like space for up to 25 minutes at a time in the last two years alone.

The ministry has no record of ever having sanctioned the use of the room, and, as Johnston told me, the school’s incident log was incomplete and inconsistently used. Nor did the Education Review Office apparently ever notice the room, which was incorporated in the unit in 2002. Institutional failures, therefore, compounded the children’s inability to describe their experience. Had a behavioural therapist not incidentally stumbled upon the room being used, we might not know to this day that it was there.

Following a familiar pattern, the Ministry of Education – in the person of head of special education David Wales – commented on the revelations in the softest of tones. The ministry had strongly recommended that the use of the room be discontinued, he told Johnston. And then: “We are very concerned about any student being repeatedly locked in a time out room. We are continuing to monitor the situation carefully.” Abuse, it seems, is only a concern if it’s repeated, and even then it only requires careful monitoring, as opposed to decisive interventions. The use of the room, says the school, “will be phased out”.

These relaxed attitudes are aided by the fact that the legality of such practices, as is too often the case with the disciplining of children, falls into a grey area. While we await the results of the Chief Ombudsman’s investigation, it is worth remarking that, according to Massey University education lecturer Jude Macarthur, the use of seclusion appears to be in breach of many articles of the Convention of the Rights of the Child, of which New Zealand is a signatory. She cites in particular:

Article 3, Best interests of the child; Article 12, Respect for the views of the child; Article 19, protection from all forms of violence; Article 28, Right to education, which says schools must be run in an orderly way without the use of violence, and any form of discipline should take into account the child’s human dignity.

What of the larger context? Minister Hekia Parata, to her credit, was more forthright than her officials in denouncing the use of the room when talking to John Campbell, but deflected more serious criticism by pointing out that New Zealand is recognised as a world leader in the delivery of special education. However, this proposition is belied not only by successive ministerial and select committee reviews, or the complaint lodged to the Human Rights Commission by IHC in 2008 and still unresolved (at what point does justice delayed become justice denied?), or the recent, damning report by Youth Law, or the petition launched last month with a rally at parliament (at which I spoke) – probably the first for this sector in our nation’s history – but also by the fact that the United Nations has explicitly rejected the idea that New Zealand is in fact leading the world anywhere.

The report on the right to inclusive education released by the Independent Monitoring Mechanism of the convention (Word, PDF) noted in particular the failure to make the right to education legally enforceable and to put it at the centre of strategy and policy making, as well as the inadequate collection of data.

To put it in simpler terms: our education ministry doesn’t monitor the progress of students with disabilities, is cavalier about protecting their dignity and safety, and doesn’t take their right to full school participation seriously enough. Stories of dysfunction, such as were heard last year by the select committee inquiry on the supports for autism, dyslexia and dyspraxia, are dismissed as isolated incidents even when they number in the hundreds. Critical failures of basic care, such as the cell that remained in full use at Miramar Central School for the past 13 years, are regarded as abnormalities to be “phased out”, as opposed to symptoms of systemic issues in need of urgent investigation and action. As a final talisman against all opposition and criticism, the government brandishes the fact that it spends close to $600 million on special education every year, as if a sum of money were the measure that the rights of children are being upheld.

Hilary Stace, a disability researcher and advocate who has recently been championing the cause of Ashley Peacock, notes that the use of seclusion on autistic children has the added effect of normalising this treatment for autistic adults such as Ashley, who has suffered it semi-permanently for the past five years (and periodically much longer than that). That is so often the case, when it comes to human rights: that denying them to one category of persons has a flow-on effect on another. Besides, there is no such thing as an isolated incident, especially when it involves a complex organisation such as a school. At the heart of it is always a culture, along with its institutions, and it desperately needs to change.