Obama wants to get the trade deal through Congress during the lame duck session, but both Trump and Clinton are vocally opposed. It is too early, however, to declare the battle lost, argues TPP advocate Stephen Jacobi

Trade has been described as “war by other means”. That inspired the US Defence Secretary, in peak hyperbole, to declare that “passing TPP is as important to me as another aircraft carrier”.

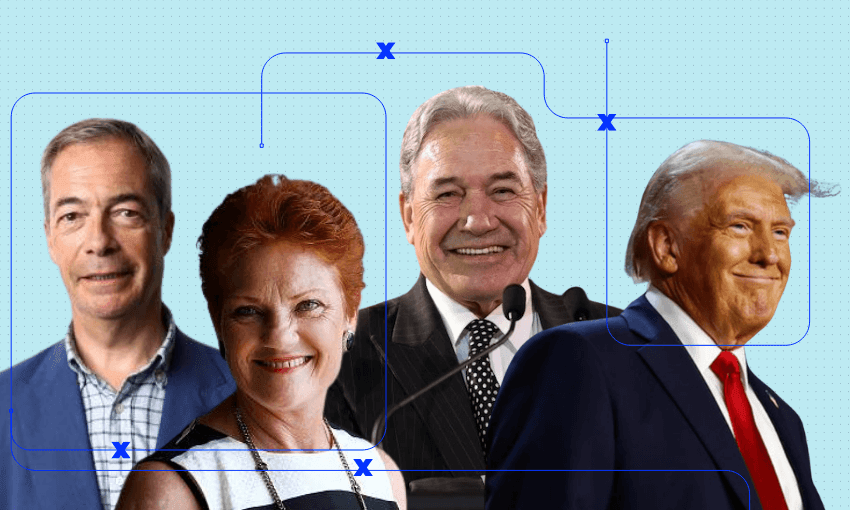

New Zealand’s interests are distinctly less martial, but placing the Trans Pacific Partnership on the altar of lost dreams is a whole lot more serious than many imagine. The world is more interdependent than ever before, although today that inter-dependence is under threat from political demagogues and backward-looking protectionists the world over.

What are the consequences and options before us if TPP does not proceed?

Where we’re at now

While TPP took six years or more to negotiate, it has been only six months or so since the signing in Auckland. To come into effect TPP requires members representing 85% of the area’s GDP to ratify – these means both the United States as well as Japan.

Eight of the 12 parties including New Zealand have commenced the ratification process. Four – the US, Canada, Chile and Brunei – have yet to get started.

President Obama is keen to see the implementing legislation passed by the existing Congress in the “lame duck” session after the presidential election on 8 November and before a new Congress and a new administration take office on 20 January.

Last week the administration took the first procedural step towards that end by sending a Draft Statement of Administrative Action to Congress. Under the terms of the Trade Promotion Authority, the president is required to give at least 30 days notice to Congress of an intention to submit the text of a treaty like TPP for a vote in both the House of Representatives and the Senate.

That draft statement does not commit the president to submitting the text, but is a prerequisite for doing so. Once the President decides to send the treaty text to Congress, which he may do at any time, the Senate and House must schedule the vote, up or down, within 90 days.

The sdministration must also submit a number of other reports including an assessment of the impact of the treaty on employment and on the environment.

The problem is that US politicians on both sides of Congress say they have difficulties with TPP. Some – on both left and right – hate the whole idea of trade, which they wrongly accuse of exporting jobs and hollowing out the domestic economy.

Others, mostly on the left, think TPP goes too far in entrenching property rights for pharmaceutical companies and giving new rights to foreign investors. Others still, mostly on the right, think TPP doesn’t go far enough in terms of intellectual property, tobacco and financial services.

Everyone seems to want to do something about so-called currency manipulation, except American currency manipulation of course.

But here’s the key point: TPP, after six or more years of exhausting negotiation, represents a careful balance – not perfect by any means, but the consensus reached between the 12 parties.

TPP is not the end of the story for the quest for more effective trade rules – in some senses it is only the beginning of a much wider initiative to create a new framework for trade and investment in the Asia Pacific region.

That’s why there is so much riding on TPP and why TPP is still a good idea which will simply not go away.

TPP is still a good idea

TPP would link New Zealand to the 11 other member economies representing 36% of the world’s GDP, markets taking over 40% of our exports and 812 million consumers.

To cut a very long story very short, the benefits of TPP would be four-fold:

- TPP would convey measurable trade advantages for all export sectors and open up important new markets such as Japan and the United States (where our competitors have better access than us)

- TPP would put in place an updated and extensive set of rules for trade and investment which we have had a hand in making and which extend into important new areas like labour and the environment

- TPP would improve the climate for inward and outward investment while upholding the Government to regulate in public health, the environment and the Treaty of Waitangi

- TPP would require little policy change in New Zealand, with the major change being an extension to copyright term.

If not TPP, then what?

If we set aside the political rhetoric for a moment, we need to remember that TPP was initiated under President Bush and has been completed under President Obama. It has not been thrust upon the American people – it has been negotiated by their representatives.

But despite the best will of President Obama the lame duck strategy may not work given the polarisation around this issue in the election campaign, with both Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump vocally opposing it.

If it doesn’t get through, then it will be for a new president and administration to address the critical economic and foreign policy issues behind TPP.

There are three broad scenarios.

One is that TPP will be completely abandoned and the United States will turn its back on decades of American-led globalism with all the implications for its trade and foreign policy interests this implies.

The other is that there will be an attempt at renegotiation. This will not be easy – why should any of the TPP partners do so when they have been so grievously let down before?

It will also not be quick – it typically takes an incoming administration the best part of a year to appoint a US Trade Representative and other key personnel.

The last scenario is that the incoming president will make the calculation that TPP is too good to pass up and will submit the treaty to Congress. This scenario cannot be totally dismissed but has been rejected by both presidential candidates.

Any delay in moving forward with TPP will give rise to important shifts in global trade policy. Other negotiations – such as the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership or RCEP, under negotiation between 16 Asian economies including New Zealand – will take on new importance. But equally, we cannot be confident that the outcome of RCEP would have the same high level of ambition as TPP.

Other groupings may also emerge, but none of them are likely to include the United States.

The very issues and concerns that fuelled the development of TPP will undoubtedly find an outlet. But this will take time – time, unfortunately, that will translate into lost opportunities.

The battle isn’t over

What will not change is that we will need to continue to connect with the rest of the world and the rules for this engagement will remain vitally important for us.

Things may not be looking good for TPP but it is too early still to declare the battle lost.

We must continue to put to our American and other friends that turning aside from TPP would represent a significant threat to all our interests.

If TPP is not the answer, then we will be faced with the daunting task of finding other options.

Making trade not war is just a much better way of using our valuable time and resources.