The decision, to be announced late afternoon, will be based on public health advice. But it is and should be a call made by elected representatives. Toby Manhire assesses the stakes.

Cabinet meets at 10.30 this morning: an early start. They will log on, most of them from their homes around the country, to make a very big decision for New Zealand: is it time to exit alert level four?

One of the strangest things about where we are today is that the sentence above will make sense to almost everyone reading it. Just a couple of months ago it would be a riddle, or bad science fiction. But that is where we live now. Clusters, curves, contact tracing: we speak a new language. There’s no live sport or theatre or pubs, but there is a daily Covid statistics call. Just when it seems absurd, comical, a blizzard hits, reminding you of the stakes. Lives have been upended, livelihoods smashed apart. It is terrible here, it is more terrible there. The world is flipped on its head.

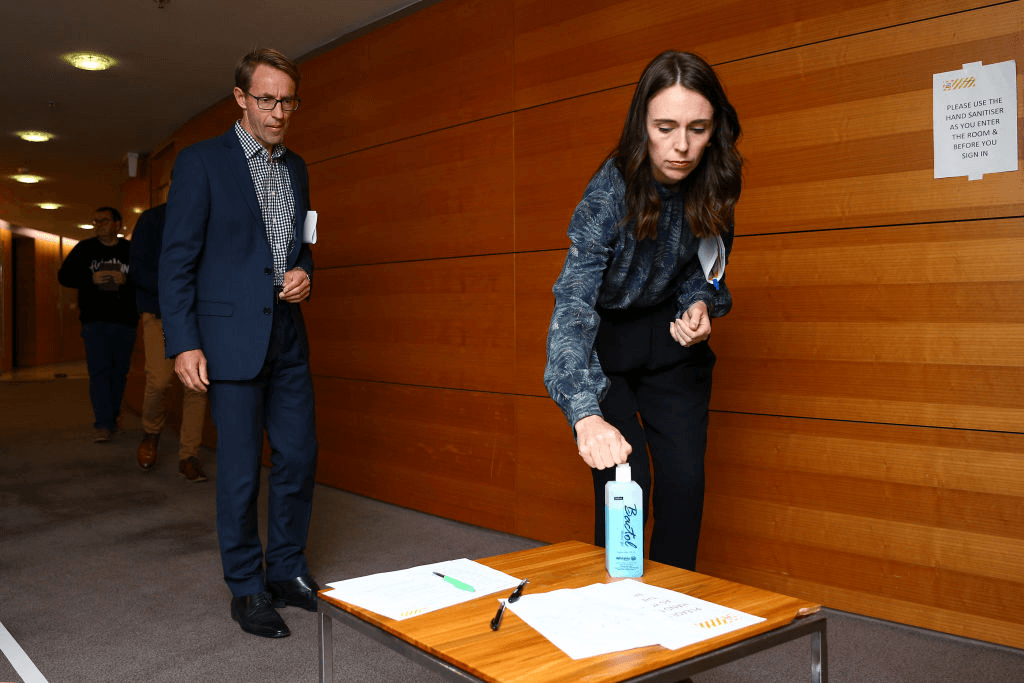

A year ago, Jacinda Ardern was being showered in praise for her response to mass-murder at two Christchurch mosques. Today she is being lauded again, most recently in a Financial Times column published yesterday that was so overcome it wanted to canonise and knight her at the same time: “Arise Saint Jacinda, a leader for our troubled times” was the headline.

The accolades are warranted, and even a fillip in locked down New Zealand. Never has the sobriquet of “the Anti-Trump” looked truer than when watching the US president’s deranged coronavirus press briefing back-to-back with that of his New Zealand counterpart.

But let’s not get carried away: the course plotted by Ardern’s government is not guaranteed. Beware anyone who tells you with absolute certainty that it means we’ll be better placed than most of the world in a year’s time – were they predicting with equal certainty two months ago that the world would be where it is now?

Cabinet meets at 10.30 to decide. Yesterday, Ardern laid out the four criteria. Border measures and quarantining need to be robust. That gets a tick. The health system needs to have capacity. That gets a tick, too, even if concerns around the provision of protective equipment, in some regions more than others, remain.

Then there’s the question of undetected community transmission. Expanding clusters or cases that can be connected to existing ones are bad. Cases without an obvious source are much worse. A form of “surveillance testing” has in recent days begun, located near the only remaining human hives: supermarkets. Irrespective of any necessary symptoms, people are tested. The good news is that so far none has tested positive. Whether enough people have yet been tested in this manner to provide great confidence that fresh outbreaks might not burst into view is another matter.

Finally, there’s contact tracing. No matter how intoxicating the downward slope of active cases might feel, there will be more cases, and not all of them will have obvious provenance. The ability to swiftly identify the people with whom a positive case has come into contact is absolutely critical to stamping out the embers of Covid-19. It always has been so: over a month ago, the contact-tracing impediments of the Pasifika Festival and the Christchurch Remembrance Service were central to the decision to cancel.

Public health expert Ayesha Verrall has completed an audit of contact tracing systems for the Ministry of Health. That report will go before cabinet today. The director general of health, Ashley Bloomfield, yesterday said New Zealand was on a path to having a “gold standard” in contact tracing. There is plenty of talk of the role of technology in contact tracing – and that will almost certainly be part of what is to come – but the more pressing question is whether the ministry can make its existing systems gel. As one person involved in contact tracing put it to me yesterday, the left hand too often has no clue what the right hand is doing.

Those, then, are the public health imperatives. They’re not the end of it, though. This is a political decision. As Ardern acknowledged yesterday, they will “look at the evidence of the effects of the measures on the economy and on society more broadly”. We live in a democracy. Blessedly, it’s a democracy deeply informed by expertise. But, thank god, it is not a technocracy. The idea that politics and public health are opposites is as silly as the binary fallacy whipped up in recent days of public health versus the economy. None of these things exists in a vacuum. Or a bubble.

Those considerations will include the number of businesses that are on the brink. The number of jobs at risk. But also the mood of the country. Since Ardern laid out the shape of life under alert level three, it’s been the talk of the two-metre-distanced supermarket queue. A lot of people are feeling knackered, wrung out, financially and emotionally, by the lockdown. For it to be described and delineated, and then denied, would be a psychological kick in the guts.

One of the areas in which New Zealand has outperformed much of the world – in the absence of sport there’s a culturally on-brand, if probably tasteless satisfaction in it – is in sticking to the programme. Polling by Stickybeak for The Spinoff shows an extraordinary 85% of New Zealanders back the government’s response – miles ahead of most of the world. That level of support is at the core of successfully implementing such draconian and strange restrictions on liberty. But it’s not set in stone. It stress-tests the social contract. Never in my lifetime has the cliché “you’ve got to bring the people with you” been more real.

Conveniently, or cleverly, the alert level three as laid out is hardly an invitation to a mosh pit. Physical distancing remains. Bubble life for most of us will be unchanged. It’s been called level four with KFC, and level three-and-three-quarters.

But it’s a step-change nevertheless. The opening of schools creates risks and confusion; like so many parts of this crisis, the pressure will be felt disproportionately by the underprivileged, and by Māori. The Early Childhood Education Council’s open letter to Ardern, published last night, pleads a reversal of the plan to reopen daycare centres under alert level three. There’s a lot yet to smooth out.

And even while many enterprises are clamouring to fire up again, some business commentators have said that as long as the strategy is elimination, we might as well be sure we’ve got it right. According to Andrew Bascand, speaking yesterday on Newstalk ZB, surveys in China are showing that enthusiasm for future travel to and trade with New Zealand has grown as a result of our response. In that light, “another week won’t make much difference”, he said.

Last Wednesday Grant Robertson, the finance minister and senior bubble attaché to the prime minister, addressed Business NZ. He trailed a shift from “essential” economic activity to “safe” economic activity under alert level three. He encouraged businesses to work quickly to establish ways to operate without contact – and with contact tracing.

That speech, via video conference, took place seven weeks and an eternity after his last. In late February, Robertson spoke at a crowded Auckland Chamber of Commerce lunch. He predicted a “short, sharp” hit to the New Zealand economy. He laid out three scenarios for the impact of the coronavirus on the New Zealand economy; in the worst of those, a global pandemic, “it may be necessary to consider immediate fiscal stimulus to support the economy as a whole and businesses and individuals through this period.” If only it were a matter of “stimulus” today.

Honestly, I remember less about what was said at that lunch than its circumstances. By chance I was sitting at a table less than two metres from where the finance minister was speaking. Spitting distance. The lunch was at the Pullman Hotel. Today, less than two months on, it is a quarantine facility for returning New Zealanders.

In the course of his speech last week, Robertson offered up the obligatory New Zealand sporting metaphor. “We can’t squander a good halftime lead by getting complacent.” To strain the analogy, we’re now in the last 10 minutes of the match, and it would be foolish to squander the lead.

Cabinet meets at 10.30 this morning. Ministers from Labour and from New Zealand First will study the advice of the director general of health, address the progress in the elimination strategy, debate the public appetite for an extension of the lockdown and the life-and-death stakes of the decision they are making. Several people will be told to unmute themselves so they can be heard.

Assuming the advice supports it, the best political decision – and it is our elected politicians’ decision to make – is to announce a short extension. To do so will cause many people real and tangible pain. To risk having to move out of alert level three and back into lockdown would cause pain, too, very likely more intense and long-lasting.

The public would likely tolerate a move to alert level three on Tuesday next week. Schools would get another six days, into early May, to steel themselves. But the end of lockdown would come directly after the observance of Anzac Day. After all, that’s only two trading days beyond midnight Wednesday. The elimination strategy gets a chance to take grip. The pace at which we return to a version of normality in alert level two accelerates. And the light at the end of the tunnel stays on.