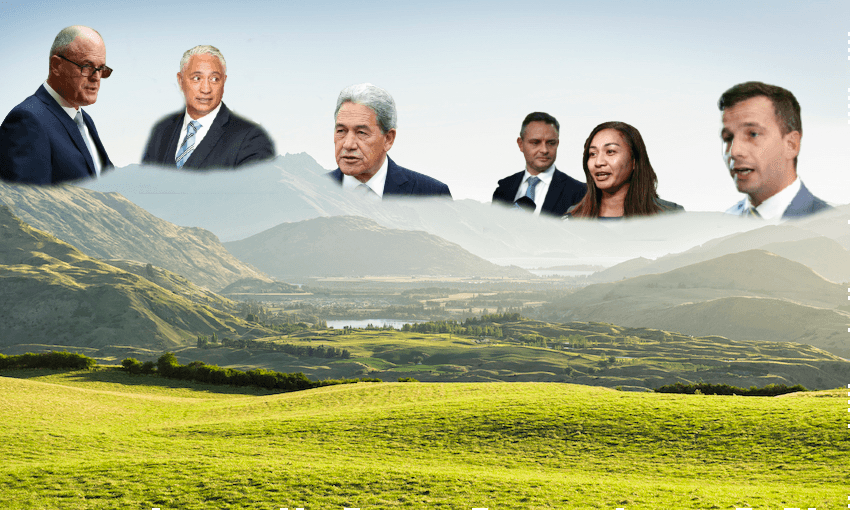

National has a new leader and it could upend parts of the political map that previously looked much more stable. So how could things change as a result?

Under Simon Bridges, National needed to get exceptionally lucky to win the next election. While the party’s polling at the start of the year was strong enough to make it happen, its lack of allies meant that any swing against the party would leave it out in the cold.

Then Covid-19 happened, Simon Bridges marred an otherwise competent couple of months with several absolute clangers, and National’s polling collapsed. Much of its previous support went to Labour, due to a combination of factors – not least the leadership of Jacinda Ardern winning over wavering voters. In the head-to-head contest between the pair of them, Ardern opened up a nigh-on-unprecedented favourability and preferred PM lead.

Now one part of that equation has been removed and the way various parties relate to each other could change as a result. Here are some permutations we could see between now and post-election negotiations, ranging from most likely to least likely.

National’s polling rises as Labour’s falls

This one barely even counts as a prediction, because of a few factors that make it highly likely. Firstly, it is highly probable that Simon Bridges’ personal unpopularity was dragging down National’s overall vote share. Even if Todd Muller turns out to be relatively bland, that’s still probably better than the alternative.

But secondly, and more importantly, Labour’s stratospheric polling is really unlikely to last. Even the party’s most ardent Ardernistas would admit that winning 59% of the vote in an MMP election is unlikely. We just don’t really do blowout wins in this country, and it would be a real surprise to see any party finish above 50%.

Parties to the right of National profit

One interpretation of the coup within National is that the liberal centrists in the party took back control from the more conservative, right-leaning faction. The subsequent elevation of liberal MPs like Nikki Kaye, Chris Bishop and Nicola Willis would support that theory, especially accompanied by the demotion of conservatives like Alfred Ngaro and Anne Tolley. These things are never exact of course – there is always give and take between factions in a reshuffle. But this perception is definitely out there, and in many ways, that matters as much as whether it is true.

So who benefits? Parties to the right of National have spent the last year jostling for space, with Act emerging as a clear alternative for those who feel National is insufficiently right wing. It’s a fairly safe vote too – even though Act is still only polling around 2% at most, any potential opponents will now find it pretty difficult to crowbar leader David Seymour out of the Epsom electorate, which gives the party a guaranteed place in parliament. If National’s polling doesn’t improve, voters who are wavering between the two parties might see little reason to settle for National.

David Seymour told The Spinoff he had enormous admiration for new deputy leader Nikki Kaye, who managed to beat Jacinda Ardern twice in the heavily left-leaning Auckland Central electorate. Seymour also said that Act now had a much more complementary role to play for those voters he described as “live and let live” – being socially liberal and economically right-wing. “If you’re someone who does actually care about liberal issues, whether it is abortion, euthanasia or free speech, Act has been pretty robust.”

The other party that could benefit if conservative voters feel deeply slighted is New Conservative. That party is currently polling at around 1%, but has no such electorate lifeline. Deputy leader Elliot Ikilei is certainly confident that voters on National’s right won’t buy the rebrand, saying “it appears that National have taken another shift to left-style liberalism, while simultaneously attempting to look more conservative, which is marketable if ideologically incongruent”. And after all, protest votes count the same as every other type of vote.

NZ First comes back into the mix

The biggest unknown of all: which way will New Zealand First go, and will it even be there after the votes are counted? For National, the position is that NZ First is ruled out – and particularly so if the party continues to be led by Winston Peters. Todd Muller has equivocated slightly on this so far, basically saying there are huge hurdles in the way of it changing. But he didn’t slam the door totally, and NZ First MPs have certainly been flirting with the Nats over recent months – while also spending the last three years playing hard to get with their coalition partners in Labour.

For National, there are serious risks in either approach. They could decide to keep NZ First ruled out, and in doing so lose a possible negotiating partner after the election. Realistically, under this scenario National and Act’s combined vote share would have to be well above 45% to form a government. They could also rule NZ First back in, giving the party a boost in relevancy that could backfire spectacularly. This election could play out in a similar way to 2002, when soft National voters rushed to support NZ First and United Future in the hopes of putting a handbrake on the inevitable Labour government.

A teal deal for the Greens?

This scenario has gone from about a 1% chance of happening to more like a 3% chance. The Greens have been pretty fierce in ruling out National in the past, with co-leader James Shaw last year even going so far as to say he “would never empower someone with as little personal integrity as Simon Bridges to become PM”. Shaw is noted as having a strong mutual respect for Todd Muller, after the pair worked together on the zero carbon bill. But co-leader Marama Davidson told Waatea News this week that Muller would still have to prove himself, particularly on Māori issues, to be worth working with. After National released an all-Pākehā top 10 in its reshuffle, that seems deeply unlikely.

Disaffected National MPs go rogue

I mean, really, who saw that whole Jami-Lee Ross thing coming? This seems deeply unlikely, because National MPs will know that disunity will sink the whole party far more than anything else. But there have been some tantalising clues. Ngaro, who as mentioned before has been bumped a long way down the list, last year speculated on setting up his own socially conservative party. And Bridges himself came out and immediately contradicted his new leader after Muller said Bridges was “considering his future” – giving every indication that he still intended to run to be the MP for Tauranga, which he is likely to hold.

Nothing at all changes, and Labour wins in a landslide

Many people thought the absolutely wild campaign shenanigans of 2014 would change the result too, and then they didn’t. It is very possible that the swing in the polls is much more solid than it appears, and thousands of voters have decided to give Ardern another three years as PM.