China’s defunct space station Tiangong-1 is expected to hit Earth in the next few hours. What are we doing, asks astrophysicist Brad E Tuckeer, to deal with the junk already in space and prevent more?

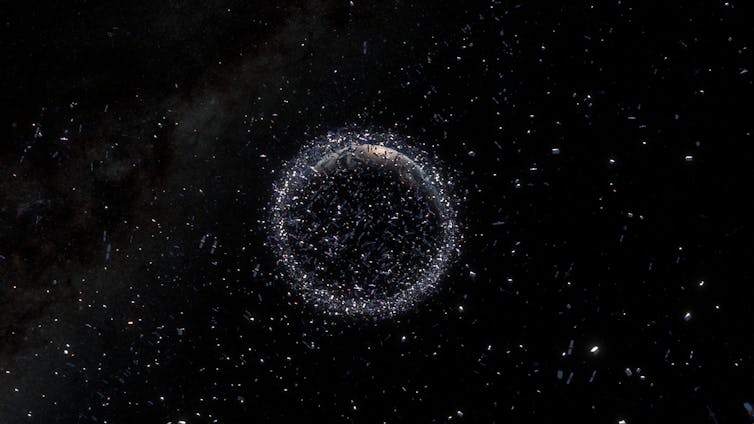

Tiangong-1 is just one of many pieces of space junk left orbiting our Earth. The United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA) says more than 8,000 objects have been launched in to space, with 4,788 currently still in orbit around the Earth.

With every launch, even more space junk is produced ranging from the rocket boosters, to flakes of paint and the satellites themselves. In 2009 an old communication satellite crashed into a new one, creating thousands of pieces of smaller debris.

By some estimates, the amount of space junk is in the hundreds-of-thousands to millions of pieces and this interactive illustration shows some of them.

From a heavenly place

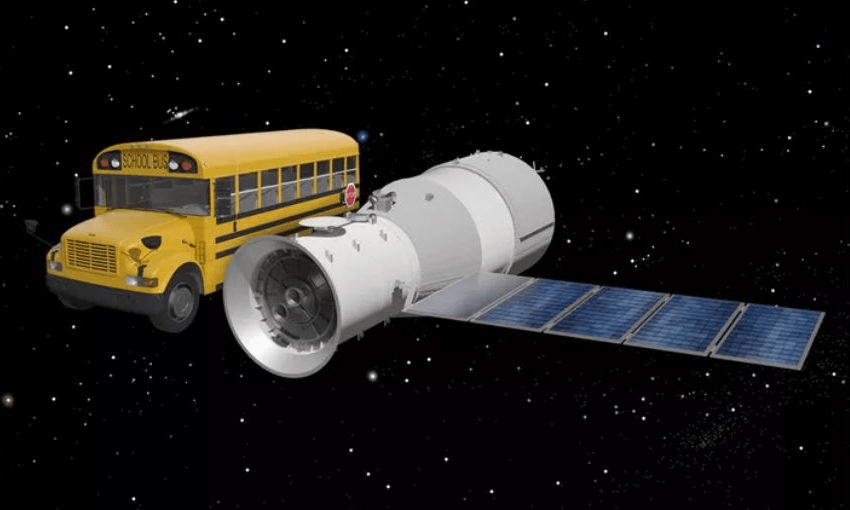

Tiangong-1, or “Heavenly Palace”, was China’s first space station – a small version of the International Space Station – and was launched in September 2011. Weighing a bit more than 8 tonnes, about 10 metres long and 3 metres in diameter, it was the first of three planned space stations.

After delays in Tiangong-2, the Tiangong-2 and Tiangong-3 were merged and Tiangong-3 was launched in 2016. Tiangong-1 has subsequently not been in use and was always designed to come down back to Earth.

But where will it crash land?

A drop in the ocean

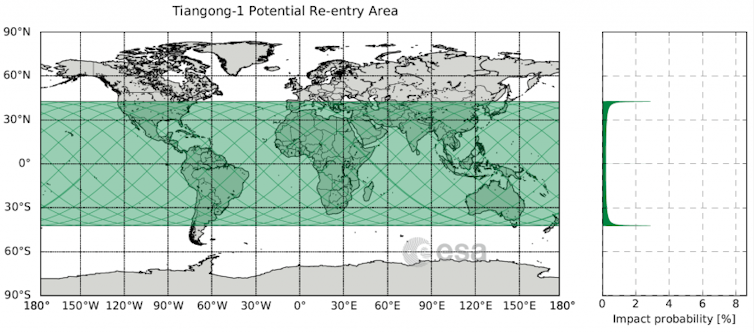

Halfway between New Zealand and South America in the Pacific Ocean is one of the most un-inhabited places on the Earth. This is the ideal location to have large pieces come back down, as the risk to lifeforms is minimal.

While most of these objects will break up into smaller bits, choosing a remote location then further minimises the risk of these bits.

In this part of an ocean there are literally hundreds of parts of automated space vehicles, rocket boosters, and even the Russian Space Station Mir, which splashed down east of Fiji in March 2001.

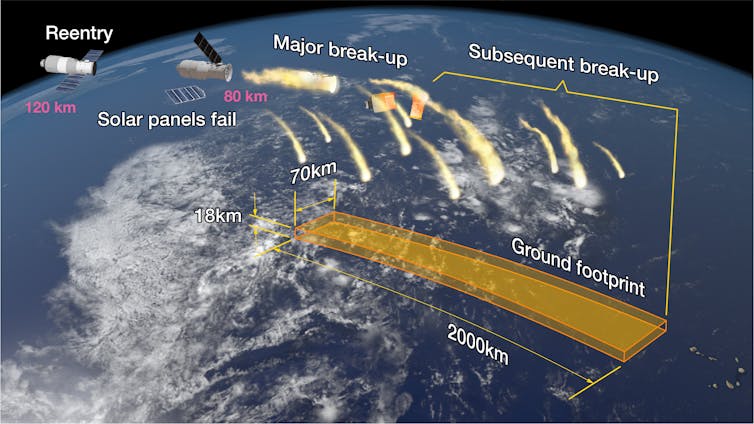

When you look at maps of satellite and space junk re-entry, the majority go straight over Australia and New Zealand. That is because re-entry starts roughly between 80km and 100km above the ground, takes around 15 to 20 minutes, and creates debris footprints hundreds-to-thousands of kilometers wide.

Therefore in order to hit the target of the southern Pacific Ocean, it must start over Australia and New Zealand.

But there’s one important feature that makes Tiangong-1 different in all of this: it is out of control, according to China’s space agency.

Crashed in Australia

If you were around in 1979 and happened to be in Western Australia, you might have a unique souvenir – part of the NASA space station Skylab, which re-entered near the southern town of Esperance.

While most missions now plan on re-entry, this was not always the case and Skylab did not have a good plan for coming back to the Earth. It was designed for a nine-year lifetime, but no clear manoeuvrability was built to re-enter at a specific point.

As news came out that it was going to re-enter, and it was not clear where, there was a varied response. Some people staged Skylab parties, others operated safety measures (such as air raid siren preparedness in Brussels).

After it hit WA, the local Shire of Esperance issued NASA with a cheeky A$400 littering fine for scattering debris across its region. It was eventually paid in 2003 – not by NASA, but by a US radio presenter and his listeners who raised the funds.

So in 2016 when China notified UNOOSA that Tiangong-1 was uncontrolled in its point of re-entry, this made scientists pay attention. Of course this made the public and media take notice, causing a bit of a panic in some coverage.

Don’t panic

Every day, hundreds of tons of debris, both human and natural (ie meteors), hit the Earth. Even those that survive re-entry and land pose a minute risk. Keep in mind, most of the Earth is unpopulated – from the oceans to vast deserts and land, nearly all people are safe.

The total surface are of the Earth is over 500 million square-kilometres. Even if a piece of space junk leaves a 1,000 square-kilometre debris field, that is only 0.0002% of the Earth’s surface.

In fact, the Aerospace Corporation has calculated the odds of getting hit by Tiangong-1 parts at 1 million times LESS than winning the lotto.

Now that you know you don’t have to worry, if you do end up being in a path that can see re-entry, you will see a show not unlike in the 2013 movie Gravity.

(Spoiler alert: Don’t watch if you don’t know the ending of Gravity.)

What are we doing about it

Of course the question has to be asked – what are we doing to both solve the junk already in space and prevent more? Well, lots actually.

A large source of space junk is all the rocket boosters and engines that are still up there and can be seen re-entering. If you remember the excitement in February around the Space X Falcon 9 Heavy launch, one of the huge reasons for excitement was that those rockets come back down safely, making them re-usable and not another piece of space junk.

Making satellites smaller not only means they are cheaper and quicker to build, but at the end of their life they can break up even more in the atmosphere, eliminating the possibility of large pieces surviving and landing.

And for all those small bits out there, Electro-Optic Systems (EOS) and Mount Stromlo Observatory are part of the Space Environment Research Centre (SERC) which is planning to build a laser system capable of safely de-orbiting small bits of space junk

![]() So don’t worry about Tiangong-1 or other space junk hitting you, we’re on it.

So don’t worry about Tiangong-1 or other space junk hitting you, we’re on it.

Brad E Tucker is an astrophysicist at the Australian National University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.