An unusual taxidermy in a Northland antique shop has ruffled feathers in the international rare bird community. Alex Casey investigates.

The year is 1788 and a curious bird that looks a lot like a stumpy, pale pūkeko is plodding around an island, about 1000km off the west coast of New Zealand. The Lord Howe swamphen or white gallinule is one of 14 landbirds native to Lord Howe Island, an Australian territory measuring just 11km long and 2km wide. While the white gallinule pokes around its swampy home on land, something devastating is happening at sea – the island has been spotted by Lieutenant Henry Lidgbird Ball of the British Navy.

In just 30 years the previously undisturbed island will have become a pitstop for passing sailors, and the white gallinule will become extinct. Having never needed to defend itself on the predator-free oasis before, the bird immediately froze at the sight of humans. “These birds were just sort of standing around and could be easily shot or just knocked on the head with a stick,” says Ian Hutton, curator of the Lord Howe Island museum and resident of over 40 years.

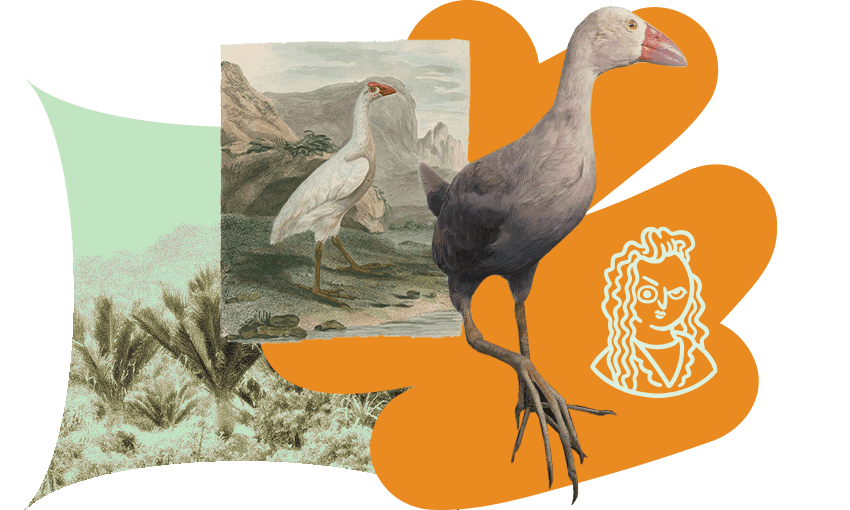

230 years later, all that is thought to remain of the white gallinule is a handful of sketches, two dried skins – one in a museum in Vienna and one in a museum in Liverpool – and one set of bones discovered on Lord Howe Island a few years ago by Hutton himself. So when an unusual taxidermy bird that looked a lot like a white gallinule was spotted in an antique shop in the Northland town of Waipū in March 2022, it certainly ruffled a few feathers.

Enthusiasts on the Leucistic Birds New Zealand page, a Facebook group devoted to sightings of local birds with unusual plumage discolouration, quickly began to comment on the strange specimen. “A bit of a mystery without background info, but nonetheless an interesting find,” wrote one member. “Imagine alive, as stunning as Mar-mite!” commented another. One international enthusiast from Italy was quick to notice the likeness with the extinct white gallinule. “I have been lucky to see and take photos of the specimen held at the Museum in Vienna”, he commented. “Indeed it more closely resembles the one in the post above.”

Elise Bailey, administrator of Leucistic Birds New Zealand, says she established the page as a way of collating information about Aotearoa’s leucistic bird population. Not to be confused with albinism, which refers to a total loss of pigment on the whole body, leucism is a genetic mutation that causes the loss of pigment in feathers specifically. “We have such a small genetic pool of DNA that New Zealand probably actually has a higher percentage of leucistic birds,” she explains. “Social media has been a great way of pulling it together, whether it is photos or just accounts of what people have seen in their garden.”

When she first encountered photos of the stuffed pale pūkeko, Bailey says her immediate reaction was “hey look, that’s a white pūkeko”. But as the comments began to roll in, her perception quickly changed. “There was a possibility that maybe it is something more unusual,” she says. “Some of the white gallinule might have been brought to New Zealand, there might be some in Australian people’s homes, it certainly would be a very exciting find.” She did note that the pūkeko is generally a lot taller and has much longer wings, whereas the gallinule is more of a “frumpy groundrunner” than the bird in the antique shop.

Hutton, the curator of Lord Howe Island museum, also admits he was “very excited” when he first saw the photos. It’s been a big year for the white gallinule on the tiny island: in the last two months the museum has received two painting donations (one from 1790 and one from 1928) that are set to become part of a new display showing the life and times of the mysterious extinct bird. “When I saw the photos I thought ‘wow, that would be nice if that was a gallinule’,” he muses over the patchy Zoom call from his office. “I think it would be extremely rare that it would end up in New Zealand, although it is possible.”

Alas, Hutton has more doubts than confidence in Waipū’s antique shop bird being a world-first find. “It just doesn’t look like it would be 200 years old, unless it was perfectly taxidermied and kept in a glass case in an air-conditioned room for 200 years,” he laughs. The feet pose a problem too: “they look a bit big for me, the gallinule had slightly smaller feet and stockier legs.” Instead of being a once-in-a-lifetime find, he proposes it might be something less exciting, but still very rare: an albino or leucistic pūkeko.

According to DOC technical support officer Tony Beauchamp, white pūkeko are “rare but reported” in Aotearoa. Referencing the white weka population, he estimates the odds of one hatching would be somewhere between one in 60,000 to one in 100,000. In 2011, four unusually coloured pūkeko were found on an Otago farm – two completely white and two boasting a “Dalmation-like” plumage. “We could not believe what we were seeing,” the farmers told the Otago Daily Times. “We’ll do whatever we have to do to protect them.” At the time, North Otago ranger Kevin Pearce said he had not seen one in his 20 years with DOC.

Andy Reilly, owner of the antique store Industry Waipū, told The Spinoff that he has never encountered an item quite like the stuffed pale pūkeko before. He purchased the bird from a Kaipara local who shot and stuffed it several years ago. “He was a collector and enthusiast – back in those days people had a shot at anything that could be a trophy.” Reilly believes the bird is “definitely” a pūkeko, although notes that “most people don’t even know what kind of bird it is.” The Spinoff understands it has recently been sold to a private collector for an undisclosed sum.

Over on Lord Howe Island, Hutton still hopes to acquire a stuffed bird for his gallinule display, even if it is just a pale pūkeko. “We thought it would be nice in any occasion, even as a white pūkeko, to have it here and display it with the paintings to tell the story about this bird that once lived here,” he explains. Even though it is over 1,000km away, Lord Howe Island has a lot more in common with Aotearoa than you might think. “Our plant life is very similar to New Zealand,” says Hutton. “I often say that we are actually closer to New Zealand than Australia in terms of the biology.”

That link is so strong that Lord Howe Island’s conservation efforts since the 1980s have all been inspired by New Zealand expertise, Hutton says. When the Lord Howe woodhen was facing extinction, it was a New Zealand bird breeder who stayed on the island for three years to increase their numbers. When all the goats on the island needed removing, it was a New Zealand company that took them all off the island. Most recently, in 2019, a rat eradication plan was entirely based on the success of similar programmes in New Zealand. “We even had New Zealand people come over to supervise the bait drops and everything.”

Elise Bailey from Leucistic Birds New Zealand hopes the mystery bird will lead more people to reflect on the weird and wonderful variations in our bird life here in Aotearoa. “It’s nice to bring an international community together to share what New Zealand has,” she says. She also hopes the curious find might encourage people to take a closer look in their own backyards: “Look outside in a tree, lift your head from the work desk, go for more walks – there’s more magical, mystical things happening than you might think.”

And 1,000km across the Tasman Sea, Hutton continues to hold out hope for the “extremely rare” piece that will one day complete his museum’s white gallinule display. For a man who stumbled across the only gallinule bones in the world while on a leisurely walk, it’s not implausible that he could strike gold twice.

“I think it would be a one in a million chance,” he smiles. “Maybe one in ten million.”