A new, more infectious strain of the Covid-19 virus has reportedly emerged in the UK, prompting the prime minister, Boris Johnson, to announce new restrictions to try to curb its spread. Dr Siouxsie Wiles explains.

Let’s start with the basics. The genetic material of the SARS-CoV-2 virus responsible for Covid-19 is a strand of RNA made up of almost 30,000 nucleotides. These are code for the amino acids that in turn give us the proteins that make up the virus. Each time the virus enters a new cell and replicates, its genetic material is copied, and nucleotides can get replaced by mistake.

As Toby Morris and I have explained before, these mistakes mean that there are now different varieties, or lineages, of the Covid-19 virus circulating around the world. Researchers around the world have been uploading their SARS-CoV-2 genome sequences to the Nextstrain website. This allows them to see how the virus is changing. From this data it looks like we’re seeing roughly two nucleotide changes happening a month which means the virus is mutating quite slowly.

Introducing COG-UK

Before I explain more about the new strain, its important to note that while the UK may have substantially bungled its pandemic response, it is doing an incredible job with genome sequencing. And that’s thanks to the COVID-19 Genomics UK consortium, or COG-UK for short.

COG-UK is a partnership between the National Health Service (NHS), public health agencies, the Wellcome Sanger Institute and a number of different academic partners, supported by 20 million UKP in government and philanthropic funding. The UK is sequencing a lot of viral genomes. And as a result it is skewing the global database of strains. In other words, just because a lineage pops up in the database as being a UK strain, that doesn’t mean it isn’t infecting people elsewhere, just that wherever else the lineage may be is not doing as much sequencing.

What’s the new strain?

It’s called B.1.1.7 and has a new combination of mutations, but I’ll come back to that shortly. Researchers from COG-UK have just posted their preliminary characterisation of the lineage and reported that there has been an increase in the number of genomes from this lineage being sequenced in the UK over the last month, suggesting it is spreading.

The first B.1.1.7 genomes sequenced in the UK were collected on September 20 in Kent and September 21 in Greater London. By December 15, this had risen to over 1600. And the sequences weren’t just coming from Kent and Greater London any more, but from other parts of the UK including Scotland and Wales. Now the Dutch government says it has also identified the new lineage in a case from early December. The Netherlands has banned flights from the UK until January 1 2021.

What’s got everyone spooked about B.1.1.7?

You know how I said earlier that we generally see around two nucleotide changes happening a month with the Covid-19 virus? Well, B.1.1.7 has what the COG-UK researchers describe as an “unusually large number” of genetic changes. It has accrued 14 mutations which result in amino acid changes. The COG-UK scientists call this “unprecedented” when compared to the genome data that’s been amassed during the pandemic so far. Again, keep in mind that many other places are not doing as much genome sequencing so the data we do have isn’t very representative of what’s happening around the globe.

Having said that, several of the mutations are in the spike protein. They are mutations we’ve seen before in other lineages, but not in combination like this. There’s mutation N501Y which has been shown to increase the binding of the virus to human and mouse ACE2 which is the receptor the virus uses to enter host cells. There’s also P681H which makes a change in the S1/S2 furin cleavage site which has been shown to promote entry of the virus into respiratory epithelial cells and to promote transmission in animal models of Covid-19.

Is the new strain more transmissible?

It might be. And it might not be. But the UK’s chief science advisor, Patrick Vallance, has said it is and even put a number on it. At a press conference, he stated that the new strain is 70% more transmissible than other circulating strains. It is not clear how he arrived at this number and as far as I’m aware no data to support the claim has been made available to the wider scientific community yet.

(Update: The 70% figure seems to come from a briefing from the New and Emerging Respiratory Virus Threats Advisory Group. The minutes of a recent telecon state: “Growth rate from genomic data: which suggest a growth rate of VUI-202012/01 that that (sic) is 71% (95%CI: 67%-75%) higher than other variants.”)

That 70% could come from lab experiments looking at how the virus enters cells and replicates. Experiments like that are useful but don’t tell us much about what actually happens in humans. A bit more relevant is looking at how well the virus is able to infect and transmit in laboratory animals. I’m not sure there has been enough time to do those kinds of experiments yet. Or maybe they’ve noticed higher levels of virus in positive nasal swabs with this lineage. If people shed more virus then they could potentially infect more people.

Or the 70% could just be based on the fact that there has been a growing number of infections caused by this lineage in the UK over the last few weeks. But it’s hard to tell cause and effect here. The UK spent August encouraging people to “Eat Out to Help Out”, cutting people’s food and drink bill if they visited a participating restaurant, bar, café, pub, or food hall. Then, around late September and early October, students started moving around the UK for the start of the new university year. Talk about a good way to spread the virus around the country! That may well have also seeded a heap of super-spreader events which has helped this variant become more dominant. More sequence data from around the world might help. Is this variant in other places and, if so, is it becoming more dominant there too?

So far it doesn’t look like the new lineage is any more deadly, although it can take months for people to die of Covid-19 so we will have to wait and see to be certain. It also shouldn’t impact on how well the vaccines work, as the vaccines make us generate antibodies that target lots of different parts of the spike protein. A serious possibility though is that the mutations could make the PCR test less effective. That could happen if any of the mutations are in stretches of RNA that the PCR test uses to identify the virus. That would be bad news for countries using the test-trace-isolate strategy to control Covid-10. But it’s easily fixed. The test will just need to be tweaked so it can pick up the new variant too.

Update: Tony Cox (@The_Soup_Dragon) from the Milton Keynes Lighthouse Lab, one of the UK’s Covid-19 testing labs, tweeted that they use a three-gene PCR test and the new variant no longer tests positive for one of the three genes (the S gene). That’s allowed them to see the rise in this new variant in the samples they test – shown in orange in his tweet below. Looks like it was pretty steady from October till late November then really started to take off. I wonder if the crowds of Christmas shoppers have helped drive its spread too?

MK LHL testing data showing increasing prevalence of H69/V70 variant in positive test data – which is detected incidentally by the commonly used 3-gene PCR test. pic.twitter.com/1U0pVR9Bhs

— Tony Cox (@The_Soup_Dragon) December 19, 2020

Is this new lineage a reason to worry?

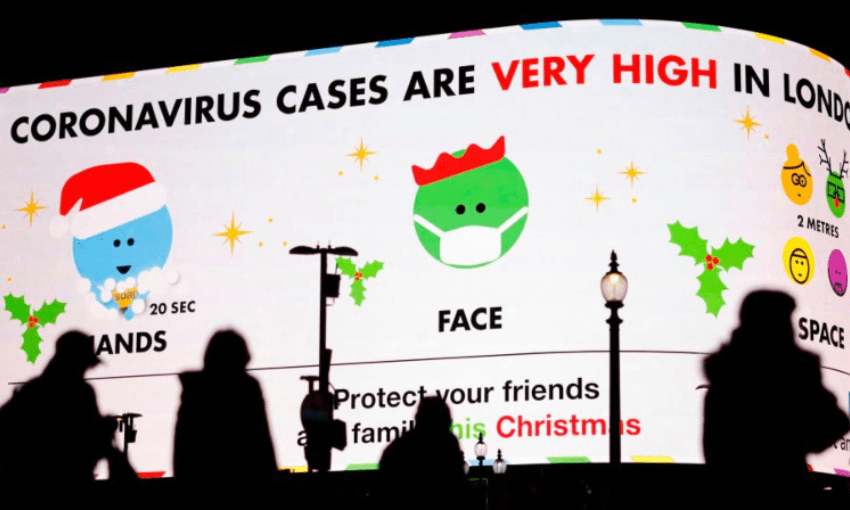

If it turns that out that this new lineage does spread more easily, the good news is that we know how to stop it transmitting between people. There are plenty of countries that are controlling Covid-19 using different combinations of controls. If there’s one good thing to come from the emergence of B1.1.17, it’s that it might have given the UK the kick it needed to do more to control their outbreak. Or at least given Boris Johnson somewhere else to lay the blame for ever increasing case numbers.

Months ago, they abandoned their original five levels of restrictions for a regional three-tier system. You can guess how well that’s been doing to reduce transmission when I tell you that even at the highest tier – so the one with the most restrictions – churches, gyms, shops, schools, and universities remain open. Cinemas are closed though. Phew.

Boris Johnson has now added a new tier saying “when the virus changes its method of attack, we must change our methods of defence”. Tweak them might be closer to the truth. At his new fourth tier, churches, schools, and universities are still open, and people can still meet one other person from outside their household. But only if they are physically outside. It’s better than tier three, I guess, but still provides opportunities for the virus to transmit. Rather than move the whole country to tier four, he’s just put London and parts of the east and southeast of England there. Which means that if this new lineage is more infectious, it’s just going to keep spreading around the rest of the country.

It is pretty shocking that nearly a year into the pandemic, countries like the UK are still not doing all they can to stop community transmission. And it is high levels of community transmission that are likely causing lineages like B.1.1.7 to emerge. There have been some reports of patients with suppressed immune systems being chronically infected with the SARS-CoV-2 virus. If most of us get Covid-19, our immune systems will clear the virus within a week or so. Yes, we may have symptoms that go on for weeks or even months, but we will stop being infectious about a week or so after our symptoms start. For those that are chronically infected, they end up shedding the virus for months.

This is how the COG-UK researchers think the B.1.1.7 lineage evolved – by someone being chronically infected. And while chronic infections seem to be very rare, the worse the pandemic gets, the more likely it is that someone somewhere will become chronically infected. And the more opportunities there will be for new lineages of SARS-CoV-2 to emerge.