In many ways, getting ready to die has been the most fulfilling project of my life. Everything after has seemed ordinary, unimportant, except for love, writes Michael Stevens

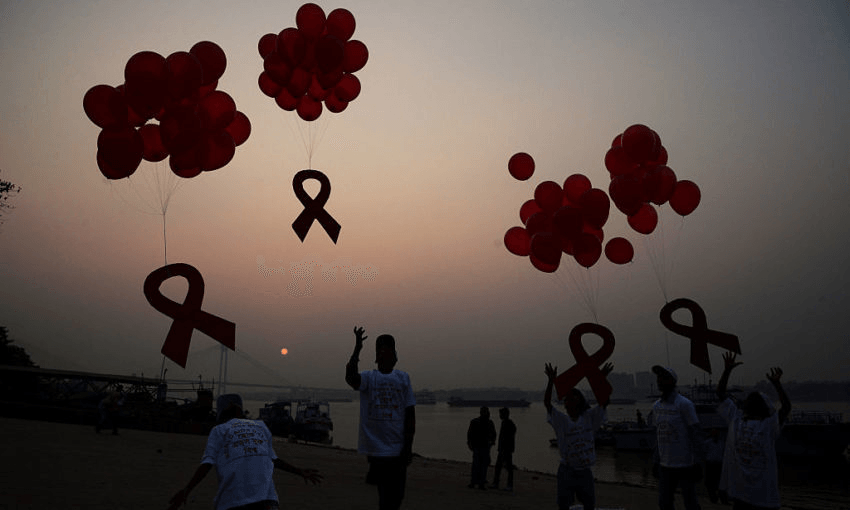

Today is World AIDS Day. It used to mean a lot more to me than it does now, but it’s still worth remembering.

I’ve had HIV for over half my life. It’s nearly killed me, it’s reshaped my world, killed men I loved, a lot of my friends and acquaintances, and even a few people I didn’t like.

In 1988 it was AIDS – we didn’t really talk of HIV back then.

I’d just been told I had it by a doctor at an expensive private clinic in London near Regents Park.

AIDS was a terrifying word, wrapping death and forbidden sex up in a particularly explosive combination. There was a lot of shame, a lot of self-hatred, and a sense even that maybe I deserved this. After all, being gay was sinful, it was wrong, that was what I’d been told growing up. I had had a lot of sex, and so much fun, such pleasure, such delight in my body, but now it was as if it had betrayed me, the joy of sex had led to this, the gates of death.

I had to go to the private clinic in London as I couldn’t get into the NHS although a doctor in the NHS clinic had listened to my story and told me I most likely did have it, and probably had two years left to live. That’s kind of chilling to hear when you’re 27. She recommended I return to New Zealand and get ready to die. The private clinic confirmed her hunch, and the doctor there was clearly not comfortable or used to dealing with it.

I remember walking out stunned, then sobbing. I expected a fairly rapid decline into sickness and then death. How would I tell my family? My friends? I was living in Istanbul at the time, in London just for the test. Could I stay there or should I take the doctor’s advice and return to New Zealand? And who could I tell?

I stayed on another five years in Istanbul, because I didn’t actually feel like I was getting sick. When I finally decided to come back here I discovered I’d been part fooling myself and part lucky. I had TB, and was pretty run down by then. It’s not an exaggeration to say that HIV took over my life.

To help make sense of it I helped run support groups for other HIV+ people. I did Buddhist meditation beside open coffins with dead bodies in them, and psycho-therapy workshops to help me adjust to my death. I went to more funerals than I can recall. And I got sicker and sicker and sicker over the next few years, with my weight going down somewhere in the low 50kgs. I was in a hospice, I was preparing to die.

Yet 30 years later, I’m still here. That’s what is so puzzling at times. That something which was such a central part of my life, something that defined so much of what and who I am is now there in the background, like a boring relative I have to listen to every now and then, who has no new stories.

I know I am so lucky. The New Zealand health system looked after me brilliantly, and I was able to hold on until the new medications came out. Western medicine proved itself again, even if it did mean I was taking 47 pills a day in 1996.

Even as I started getting well, another doctor here told me I probably had a year to live. So that was twice I was told to get ready to die by doctors before I turned 40.

One of the hardest things to do was to learn to trust I had a future again, to plan. But I did, returning to university, always a spare pair of undies in my bag along with the pills, because the pills had a nasty side effect I couldn’t always be ready for.

Death had been my intimate companion for so long, it now seemed hard to accept he was no longer peering over my shoulder and watching my every move, and waiting.

In many ways, getting ready to die has been the most fulfilling project of my life. Everything after has seemed ordinary, unimportant, except for love.

I know I am lucky. So lucky, to still be here, to be alive, to be in pretty good health, with access to life-saving medications and a public health system that works.

So many others around the world are not, and that is always a sobering thought. If those new medications had only become available here six months later, there’s a good chance I wouldn’t have made it. Luck plays a huge part, luck and privilege.

While HIV/AIDS will never leave me, its effect has lessened now over time. It is part of me, in a very real and physical sense. It’s part of my body, and like a drop of ink in a glass of water, it can never be removed. It’s just a virus trying to do what it wants to with no malice, no intelligence to it, only now it is held in check.

So many people are still terrified of it, so many people who live with HIV are paralysed with fear and anguish because of it. So many of you who don’t have it judge us, shun us, or turn us into a punchline for a joke. The stigma attached to HIV/AIDS is greater than any other illness I can think of, precisely because of its connection with sex, especially anal sex between men, and death. So many young gay men have no idea of what it was like, and maybe that’s a good thing.

I’m alive, and I live, and I love and am loved. And I’m lucky, so lucky. I just wish so many of the people I knew from those days could say the same.

The Bulletin is The Spinoff’s acclaimed, free daily curated digest of all the most important stories from around New Zealand delivered directly to your inbox each morning.