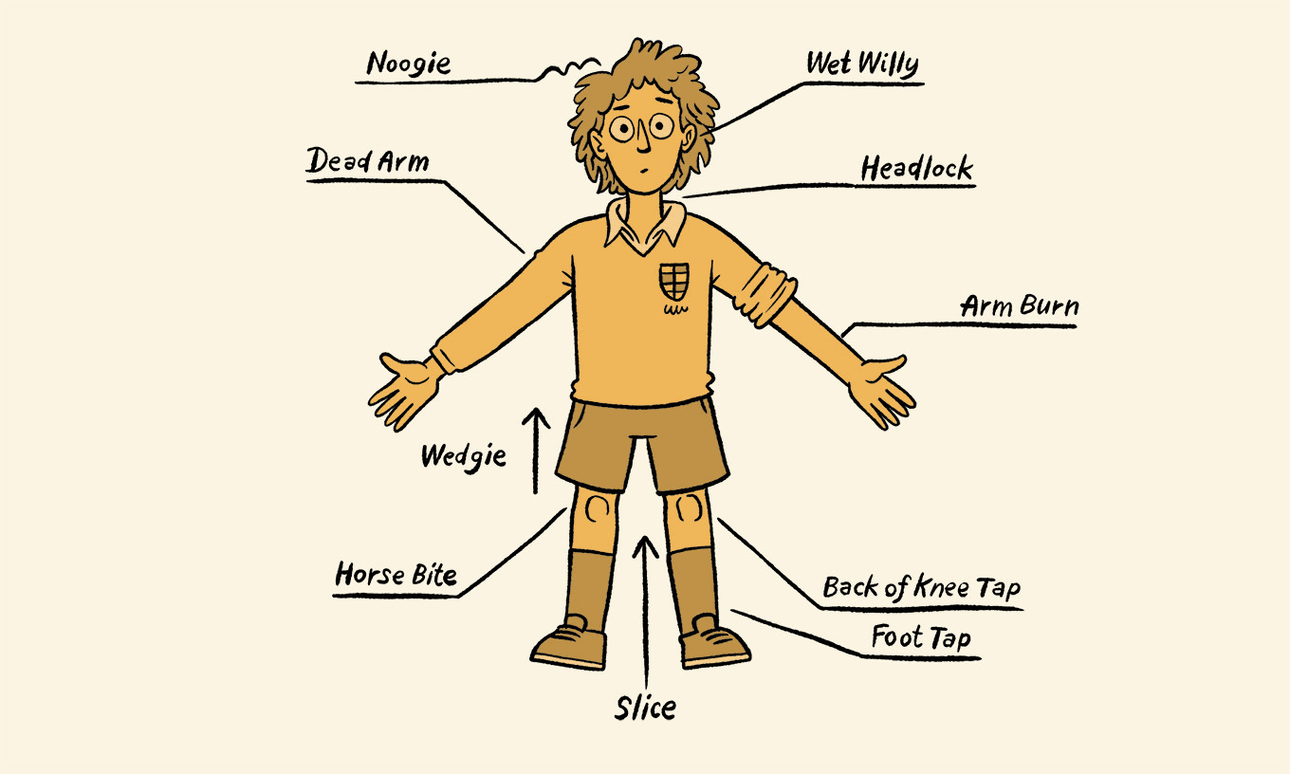

Do your childhood memories include being randomly attacked by your classmates? Josie Adams and Duncan Greive look back at the strangely violent schoolyard culture of dead arms, noogies, tabletops and more. Illustrated by Toby Morris.

They say your school years are the best of your life. Remember being nine, playing marbles, and swapping your fruit roll-up for half a Cookie Time? Remember being 12, wearing butterfly clips, and glugging your first energy drink? Remember Jump Jams, and MTV, and how wedgies and chair pulls swept the school in viral waves?

Looking back, some of our “best years” were spent physically attacking each other, in a way that is absolutely shocking to us as adults now, but seemed as inviolably part of school culture as uniforms at the time.

One afternoon, after work, a group of Spinoff staff began discussing the phenomenon, and found it transcended gender, ethnicity and geography. There were regional variations, some that came in a craze and never returned, others that were there on some level from primary school to high school. We fervently hope the children of today have moved on to gentler things.

We gathered the below to function as a kind of cultural history – a way of saying that this really happened. What we’re explicitly not doing is saying that it was good that it did. It’s also important to say that these activities, many of which would be considered different varieties of assault were they to happen between adults, often happened between the closest of friends, with a form of implied consent.

They also happened in contexts that were unequivocally bullying. Which, it shouldn’t need repeating, is an appalling culture that occurs throughout New Zealand society, in both physical and psychological forms. That these activities could seamlessly move between relatively harmless fun to a tool in the trade of some very destructive behaviour is part of what makes them so mysterious. And fascinating – it’s an area of our cultural history about which there seems to be no scholarship, no theorising. This just happened, to almost all of us, and no one seems to know why, nor particularly talk about it.

So here they are, described for seemingly the first time in one place, the petty, destructive, dangerous, undeniably real physical attacks of the New Zealand playground, dating back at least to the 70s, and definitely still in practice as recently as the 2010s.

Arm burn

The arm burn was more often and very racistly known as an Indian or Chinese burn, despite being inflicted by all ethnicities. It involved grasping someone’s forearm with both hands, and twisting each hand in a different direction, quickly, causing a friction burn.

Strap slap

If you wore a bra to school you had to keep it hidden for fear of the strap slap. Any visible bra strap would be pulled back and let go, slapping your shoulder with red hot elastic. You’d think this was exclusively girl-on-girl violence, but it’s not. In our experience, most strap slaps were committed by boys.

Pretty painful, and with the added effect of damaging expensive underwear. It’s hard to tell if the inventor of the strap slap was shaming girls for entering puberty, or just making the most of an opportunity.

Noogie

The act of grinding knuckles into a mate’s head, mostly in a headlock. Not super painful, but very uncomfortable.

Headlock

Not a proper wrestling technique – an arm around the neck to keep someone’s head still while deploying other attacks, mostly noogies and wet willies.

Slice

Not painful, just weird. The hand, in a chop position, swipes up the crack of the uniformed arse – quickly enough to surprise. The attacker calls out “slliiiiiiice!!!”, and girls would also slice each other in the front. Slice seems particularly popular in Dargaville.

Foot tap

A form of trip, tapping the ankle just as it heads forward during the normal walking motion, and mostly resulted in a simple stumble, with the odd grazed palm.

Knee tap

Related – this took advantage of the knee’s reaction – when aimed just right a relatively light tap would see the leg briefly collapse.

Horse bite

The hand, in pincer position, clamps down hard on the lower thigh just above the knee. The attacker squeezed hard and very quickly, focusing on either side of the leg.

It felt like your patella was about to pop off. Really effective delivery of a quick, intense – but mercifully brief – burst of pain.

Body glove

Slapping someone’s back with an open hand will leave a searing red imprint in the shape of the Body Glove logo. Mere seconds of pain, but the imprint lasted for minutes.

Pinkie

The same as a body glove, but on the thigh instead of their back. The Spinoff managing editor Duncan Greive has been pinkied “maybe 500” times, indicating that this was particularly endemic at Auckland Grammar during the 90s.

Wet willy

Stick a finger in your mouth so it’s all slobbery, and then jam it in a friend’s earhole. Twist. Disgusting, but not painful. Covid-19 provides yet another reason why this should no longer happen.

Down trou / down trail

Pull the victim’s pants down, revealing (hopefully) their underwear. Tended to set off a war which could last anywhere from minutes to days.

Tabletop

A rare attack which required two people to execute. One distracts the target from the front, while the other crouches on hands and knees behind the target’s legs. This second person is the “tabletop”, because they look like a table. Person one pushes the target backwards, and the tabletop will cause their legs to fly out from underneath them. More humiliating than painful, for the most part.

Chair pull

Also known as the “invisible chair”. When someone went to sit down, someone would rip the chair away, causing them to fall to the ground, butt first.

Wedgie

The earliest known loincloth dates back 7,000 years and that’s likely how old the wedgie is, too. From behind, the attacker grabbed the victim’s shorts or underwear and pulled it up, hard. Material would gather in arse crack, giving it a good flossing. At times the recipient would be lifted off the ground.

Dead arm

A quick anatomy lesson: likely without knowing it, the attacker was aiming for the brachialis muscle, a very specific spot on the arm, about 10cm below the shoulder. Commonly delivered as a suckerpunch, there were also variations, near exclusively involving boys in their early teens, where two or more would participate in a dead arm competition.

It hurt a lot for a hot second, and then went totally numb, the arm unable to move.

Free hit

In New Zealand, fire hydrants are marked on the ground with a yellow “FH”. To anyone in the know, this stands for “free hit”, and playground law had it that you’re allowed to punch the nearest person, mostly in the arm (see above). Variations saw free hits also granted to anyone who saw a yellow car (“hit yellow car”) or a Volkswagen Beetle (“punchbuggy”).

The free hit remain common to this day, while many of the above remain, thankfully, as fading memories of those who went through the New Zealand school system in the 70s-00s. It seems likely that schools’ tolerance for this kind of behaviour, which stretches from harmless hijinks to dangerous assaults, has significantly diminished in these more enlightened times. But this happened, and was an ever-present part of school, likely for millions of us. Let this post be a reminder of the weird, creative violence of children.