What’s in a name? A lot, when it’s Eric Frederick Trump.

When the boxer Butch is making a getaway in the back of a taxicab in Pulp Fiction, he sees from the ID card on display that the driver’s name is Esmerelda Villa Lobos.

“That’s a hell of a name you got there, sister,” says Butch.

Esmerelda asks her fare his name and, upon hearing it, inquires, “Butch…What does it mean?”

“We’re in America, honey,” he explains. “Our names don’t mean shit.”

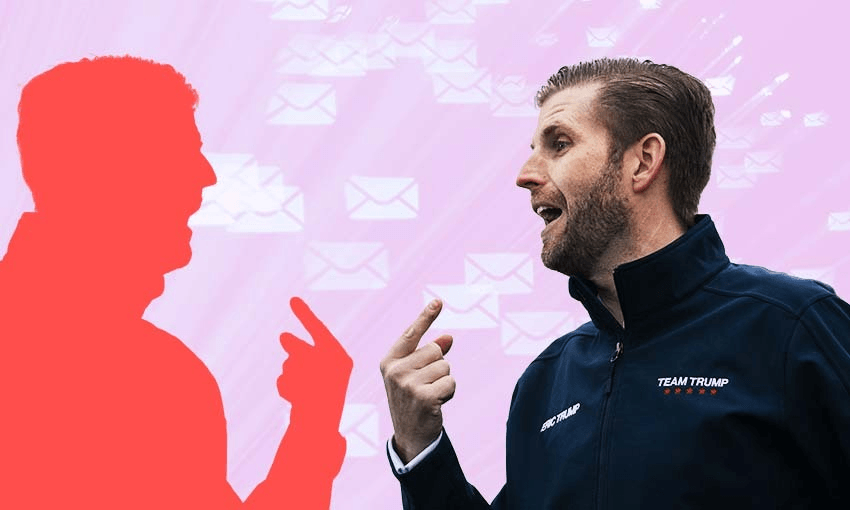

If only. Names denote and perform – they conjure. They can have consequences or shape the contours of a life (just ask Rumpelstiltskin, or Anthony Weiner). I won the doppelgänger trifecta with my name: Eric Frederick Trump, the replicant name of Donald Trump’s second son. Our monikers are onomastic twins down to the last letter. Our parents even built into our name a tautology, perhaps sensing we’d be double-goers: Eric Frederick Trump. Like our hometown of New York, NY, Eric and I were so good they named us twice.

It’s a terrible deal…a terrible deal. My name, which was imposed upon me before my namesake, has, in the age of Trumpism, broken away from me to become its own signifier, a vector into the wilds of Trumpland. I was thrown into not an alliance with Eric Trump, but a psychosis of association. My digital and real mailboxes stretch with misdirected adulation, desperation, and entreaty. The single threat I’ve received has a tone that toggles between the Symbionese Liberation Army and a slightly off-kilter lawyer: “You will be hunted down and returned in chains. Bear in mind your actions may be considered to have been like being a traitor.”

Name homonymy means I’ve become an apprentice to a celebrity, our name nurturing an unsought fictive kinship between Eric Trump and the Other Eric Trump. He’s always with me, my flesh-colored shadow. Like others in this age of proliferating identities, I long for a new pronoun, one that embraces my onomastic twin and me. We are like characters in a Gothic tale, separate but joined in name – and occasionally indistinguishable, as when Eric Trump wakes up in Dunedin with a case of the fuckarounds and answers Other Eric Trump’s mail.

When my family and I left New York for New Zealand, the day Joe Biden was declared president, we felt liberated. New Zealand beckoned like a floating, reality-based fortress with a water wall around it wide enough to make the Don envious and a captain whose hand was firmly on the tiller. Tucked away in Dunedin, after two weeks in exquisitely managed isolation, I thought, “here at last, among the penguins and albatross, I will be as far from the Trumpian clamor geographically as I am politically”. Wasn’t it the Austrian philosopher Karl Popper who wrote, disorientingly, that New Zealand was, after the moon, “the farthest place in the world”?

Not far enough, apparently. Eric Trump, the name, is the background radiation of my life. Recently, a journalist at an American newspaper, one that has won more than 20 Pulitzer Prizes, reached out with a simple request: Can you, Eric Trump, confirm the sale of the Trump International Hotel in Washington DC, and do you have any comment? After a quick search – about as quick as the one that led the journalist to me – I confirmed the hotel was being sold to CGI Merchant Group. And Eric Trump did indeed have a comment: “Heavy hearts all around. I think it’s safe to say no public figure in the history of the United States has been persecuted the way President Trump has.”

A stray comment flapping its wings in New Zealand unleashed a media squall in the US. Readers raged: “Crybaby.” “Always the victim.” One commentator wrote: “So when Eric tried to blame the selling…on the Democrats, it seemed like he wasn’t even trying.”

But Eric was trying. He always tries.

This brings to mind another message, heartbreaking in its content. It’s from a former contestant on Donald Trump’s reality competition show Celebrity Apprentice. They recall milling about between takes, when Eric Trump walked by and Donald looked up and said “out loud for the entire crew to hear, ‘There he is, there’s stupid!’” Magnanimous, they go on to write, “I don’t approve of your dad. I never did. I only wish you had a positive male influence that loved you.”

I didn’t respond to that person. I thought of Donald, I thought of Eric, I thought of all the sons and fathers, and how the shadow of paterfamilias can be especially dark over sons. It’s not easy being a son. Eric, do you sometimes stammer somewhere between speech and silence when standing before your imposing progenitor? My brother, my twin, I know you do.

Other voices, other sentiments, ricochet in my message box. Someone from Greece suggests this strategy to beat the Democrats: “camps at the border & fire chambers for them they deserve to be fried alive.” Steady on.

A sender from Texas, subject line “Praying for your dad”, was doing just that precisely the week my father actually died. Their uncanny message was strangely consoling. It read, in part (some of these messages are thousands of words long): “3 of us, as angel princes, will stand by him…we will lock horns with the enemy and raise your father back up.” The part of me that believes in fairies wanted to cry, “When?” Nameless in Korea tells it slant: “I love Donald Trump really. I want to know true. Please help me.”

I find myself wanting to know true, too, especially when it comes to Eric Trump, this strange hybrid creature forged from passion and politics and celebrity and technology. In the post-truth age, the era of “alternative facts,” ushered in by Donald Trump, identity has reached a precarious moment. As someone who has two passports and a kidney transplant that is 30 years older than the rest of his body, the freight of this self-willed name renders the question, “Who am I?” acute sometimes. I mean, in one sense Eric Trump is. In another, he’s not.

And yet. If I ever encounter Eric Trump, my double, (a risky event if fairy tales and Sigmund Freud are to be believed), I will wait for the clouds to cease boiling and the thunder to stop rolling, and I will reach out to touch my doppelgänger and say, “That’s a hell of a name you got there, brother.”