A recent opinion piece on the Spinoff warned of the dangers of voluntourism, a term for programmes that charge travellers for short-term volunteer experiences. Here, two volunteering organisations tell Josie Adams why what they do is different.

A tourism-volunteering hybrid, the burgeoning industry of “voluntourism” has been criticised for charging westerners thousands while costing communities in developing nations by robbing them, detractors say, of long-term, sustainable workers and industry. At their worst, such programmes stand accused of feeding a white saviour complex.

Some volunteering organisations, however, are concerned that they need be conflated with the voluntourist crowd. Their programmes, they stress, have academic grounding and international accreditation.

Stephen Goodman, CEO of Volunteer Service Abroad, notes that the first president of VSA was none other than Sir Edmund Hillary, someone whom, he says, exemplified the spirit of true volunteering in his work in Nepal. VSA doesn’t charge its volunteers gratuitous fees to apply or go on assignment, and it doesn’t place volunteers in assignments for which they’re not right.

“VSA was founded to give New Zealanders who’ve got skills and experience the opportunity to go into communities where those skills and experiences aren’t present, to work alongside those communities and pass on those skills,” says Goodman.

It’s for this reason that VSA doesn’t narrow its focus onto bright-eyed university students. Goodman estimates about 50% of VSA’s volunteers are in their early 50s or older. Roughly 30% of its volunteers currently overseas are over 60.

“We might have an early childhood teacher, or a language instructor, or an engineer. What they’re bringing is all their professional experience and life experience,” says Goodman. VSA’s volunteer assignments are often very specific, with the postings treated like job applications.

UniVol is VSA’s dedicated student volunteer programme, targeted at university graduates (or near-graduates). The programme was designed for development studies graduates, although it’s now opened up to other disciplines, and consists of a 10-month volunteer period working alongside a counterpart from the local community in a development-related field like communications, youth work, or public health.

Professor Tony Binns, an Otago University development studies lecturer, was instrumental in designing UniVol.

“All students entering the UniVol programme must have studied courses in development at university and be aware of the different interpretations of the meaning and practice of development,” he says. “In such courses we are critical of voluntourism and emphasise the importance of a detailed understanding, developing empathy, avoiding stereotypes and working toward improving the quality of life among households and communities.”

UniVol, like all VSA programmes, includes a two-day selection weekend and four-day course. Applicants must go through panel interviews and counselling so both they and VSA understand their motivations and skillset.

“I am always rather sceptical about those who say they want to ‘have a good time whilst helping local people,’” says Binns. “I believe the fundamental asset required of good volunteers is the need for a relatively detailed understanding of the concept of development. But every situation is different, so demonstrating a willingness to find out more about local society and culture is crucial.”

While VSA precedes modern voluntourism, another organisation was founded as a response to it. International Volunteer HQ was set up in 2007 after its founder went on a volunteer trip to Kenya and came away disillusioned. “Since then, IVHQ has existed to provide affordable trips that enable volunteers to make a genuine difference in communities around the world,” says community manager Nick Walker.

IVHQ doesn’t offer placements in orphanages, doesn’t charge volunteers exorbitant prices like many for-profit volunteer businesses, and regularly visits partner organisations to ensure the communities’ needs are being met appropriately, he says.

“Locals, not foreigners, are determining the focus of the volunteering. They understand the community need and cultural nuances surrounding each project, so this makes sure volunteers are contributing to projects that genuinely benefit from their support.”

“IVHQ is the only volunteer travel company to be a certified B-Corporation, as believers in using business to do good,” said Walker. “We’re also the only volunteer travel company to be a member of the Volunteer Groups Alliance (VGA).” VGA is aligned with the United Nations and its 2030 agenda for sustainable development.

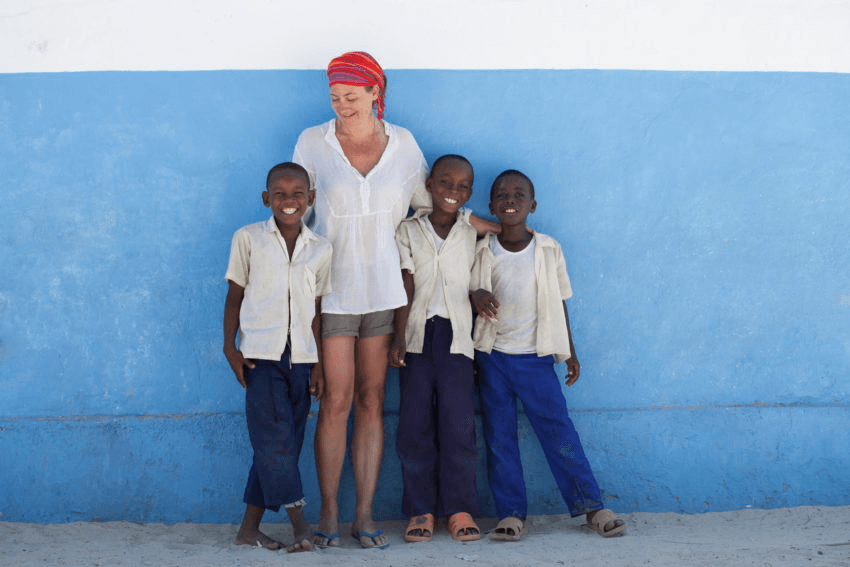

Kari Holmgren volunteered with IVHQ in Muizenberg, South Africa, for one month. “I am aware of some of the criticisms of volunteering. That is one of the reasons why I had trouble finding volunteer organisations,” she says. “I didn’t want to be a part of any of that.”

In Holmgren’s opinion, IVHQ is one of the “good guys”.

She worked at a school. “I’m not a teacher so I was a little limited on what I could do.” She ended up checking students’ workbooks, brainstorming teaching activities, and in general provided assistance where needed. “Even though I’m not a teacher I feel like I was suited for the role,” she said. “If I had any questions or didn’t feel comfortable doing something, all I had to do was let my teacher know. She was very understanding.”

A similar attitude prevails at VSA, says Goodman. “We very much adhere to the view that capacity-building is about relationships. It’s about time. You put someone into a country for 12 months, and the first third of that is about building the relationship, which leads to them more effectively being able to pass on knowledge and engage. It has to be sustainable.”

Organisations like VSA and IVHQ are clear that it takes more than time and money to make sustainable change. Volunteers need the right motivation and mindset to be prepared for months or years in a wholly different environment, and businesses to focus on sourcing feedback from local communities as well as those the volunteer works with in an official capacity.

“Every volunteer that comes back will have engaged different groups via churches, sport, cultural groups, whatever,” says Goodman. “This is their life.”