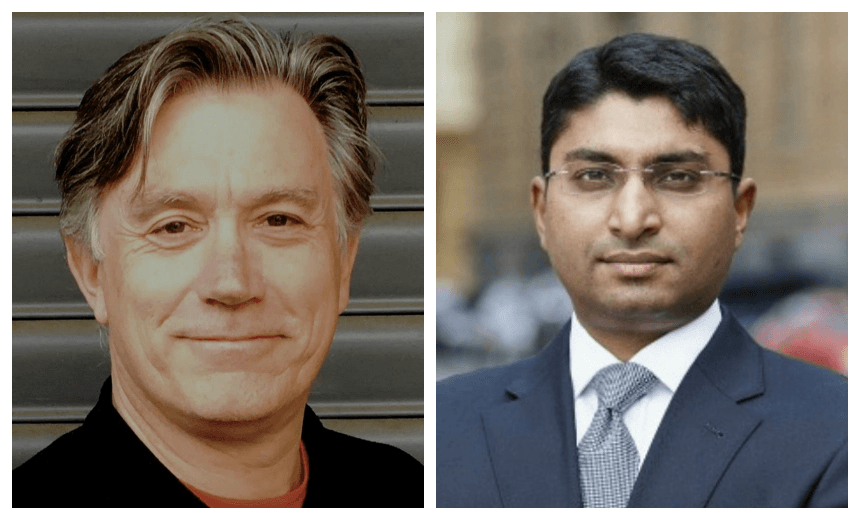

‘Via their KiwiSaver accounts, ordinary New Zealanders are beginning to buy back New Zealand. They deserve to have a say in how the companies they own are managed.’ Sam Stubbs, GM of Kiwisaver provider Simplicity, and economist Shamubeel Eaqub – a Simplicity board member – explain why they’re putting Simplicity’s funds to good use.

KiwiSaver is the first successful mass market savings product in a generation. It’s well-regulated, well-trusted, and growing fast. It’s already $41 billion big, and Treasury estimates it will be a $200 billion savings pool by 2030. Around half of that will be invested in our local share and bond markets by 2030, which is the equivalent to 30% of GDP, and 66% of New Zealand’s current share market capitalisation.

This is a rising tide of capital, and a king tide at that. In our lifetime, New Zealand hasn’t seen anything like it. NZ companies have traditionally been starved of capital, largely due to a tax regime which heavily favours real estate investment. To compete, companies on the stock exchange have to pay high dividends, restricting their ability to fund R&D and investment.

We think that’s about to change, big time, and we wonder whether the companies, and KiwiSavers, have fully embraced what this means. Via their KiwiSaver accounts, ordinary New Zealanders are beginning to buy back New Zealand.

As owners, they deserve to have a say in how the companies they own are managed. At Simplicity, since launch we have had over $170m come into our funds in nine months, and it’s our ambition to eventually own more than 5% of every listed company in New Zealand on behalf of our members.

We intend to use these ownership stakes to actively push New Zealand businesses into behaving in ways which benefit both themselves and this country. It’s called being an ‘activist investor’, and we intend to use our voice to help transform our business sector into a more diverse and far-sighted place (more detail about those goals deeper in this piece).

For a long time fund managers in New Zealand have been pretty quiet. They roar about the value of takeovers from time to time, but by international standards, they are a fairly passive bunch.

Why so quiet? One reason is the traditional New Zealand way of having a private word rather that a public fight. But there is an inherent conflict of interest too. Let’s face it, the banks and insurance companies, who dominate KiwiSaver, want to lend these New Zealand companies lots of money, and sell them services. Doing so is very profitable. Why upset management of companies when you want to sell them something?

So, as good as they are, fund managers in NZ are often muzzled by their management. When did you last see a fund manager working for a bank criticise a big company in public?

Measuring time in decades, not quarters

This short termism is bad news for KiwiSavers. They are saving for decades, and the companies they are invested in need to thrive on the long term, not shine in the short. Their KiwiSaver manager should play a key role in encouraging long term thinking. That makes them richer in their retirement, and allows the companies to hire more Kiwis in added value jobs.

Companies also need stakeholder support to make the tough decisions that will underwrite their future. The best example here is with spending on R&D (research and development). It’s persistently lower in NZ than nearly all of our international peers. Why? Because given the option of investing in R&D or paying a bigger dividend, CEOs get the ‘show me the money’ message from retail shareholders, and silence from the institutional ones.

How many times have you heard a CEO say ‘we could pay a bigger dividend, but it’s best we spend it on R&D for long term shareholder benefit’. Why not? Because too few large shareholders stand up and applaud this. Where it makes sense, Simplicity will.

The plan to increase executive diversity

If a picture paints a thousand words, looking at the photo of NZX-listed company boards would tell you we live in a country dominated by white men, with a few women and almost no Māori, Pasifika or Asian leaders. Diversity is seriously lacking in our listed companies. And this from a country that gave women the vote first.

Here are the sad facts: just 4% of CEOs and Chairpersons of NZX 50 companies are women. Only 13% of Directors are women. Even fewer are Māori, Polynesian or Asian. All this is likely because just 33% of listed New Zealand companies have some form of diversity policy – meaning two thirds do not.

This contrasts with public sector boards, where significant progress has been made through a dedicated programme to increase diversity. Public sector boards now have 43% women directors, with 45% of senior leadership roles within the public sector held by women.

We want to see that come to the private sector. Simplicity, as a shareholder in all the NZX50 companies, has asked each one to plan for full diversity over the next six months, and to have it fully implemented in five years. With enough time, and a clear direction, this is absolutely achievable.

The facts are indisputable, and progress has been slow, witnessed by the ongoing research of Professor Judy MacGregor at AUT. Too many workplaces still insist on rigid work hours for managers, with insufficient allowances for the realities of parenting and higher pressure roles.

The evidence is overwhelming that diversity is great for business. The Petersen Institute released a study in 2016 showing that companies which embraced diversity significantly outperformed those which failed to. It’s just one of many studies showing a positive correlation between diversity and shareholder returns.

Quite apart from the clear benefit to investors, though, isn’t this also the New Zealand we want to live in?

So from today on, in conjunction with leading academics, Simplicity will monitor progress and regularly publish results. We’ll work with AUT diversity researchers to keep accurate data on the process. We’ll praise those companies working sincerely towards it. Conversely, as a shareholder, will have a range of options available for those who don’t.

What does diversity in this context mean? It will be what works for the company. It could be by gender, ethnicity, age or ability. Each company has different customers, employees and stakeholders, and diversity must reflect whats best for their long term growth. We do not support quotas, which create artificial notions of acceptability. When you see pictures of the board and management, it’ll be obvious whether diversity has been achieved, or not.

Why ask companies to implement full diversity over five years? Because it takes that length of time to effect structural change. Five years allows for orderly Board rotations, the promotion of diverse talent, and policies to accommodate parenting and modern work practices. True diversity is unlikely without a root and branch overhaul of those practices which prevent it.

We expect companies to welcome this, and embrace the change. In a recent visit to most NZX Top 50 CEOs, we were greatly encouraged by their desire to have a long term stakeholder who has their long term interests at heart. They want to feel empowered by their shareholders to make decisions for the benefit of all. They care passionately about the companies they work for, and want the best for New Zealand.

As a KiwiSaver manager, we are here to make our members wealthier in retirement, and do this with a conscience. In most cases, what’s good for long term, sustainable business is good for our KiwiSavers, and good for NZ. As an owner and long term stakeholder, it’s our responsibility to advocate changes for the best long term welfare of our members, and NZ.

We can have fully diverse governance and senior management in all of New Zealand’s biggest companies within five years. It can be done. As a shareholder of behalf of our members, Simplicity is determined to play its part.

The Society section is sponsored by AUT. As a contemporary university we’re focused on providing exceptional learning experiences, developing impactful research and forging strong industry partnerships. Start your university journey with us today.