The region is known to lack many of the advantages of central and north Auckland suburbs, yet properties command rents as high as the likes of Mt Albert and Ōnehunga. So how do landlords get away with charging so much, Justin Latif asks.

If you write the words “is South Auckland” into Google, the first three search options are “is South Auckland safe”, “is South Auckland dangerous” and “is South Auckland a ghetto”.

But you would have to pay me to live anywhere else in this sprawling mess of a city. Nothing beats the south’s vibrancy, warmth or inspiring resilience.

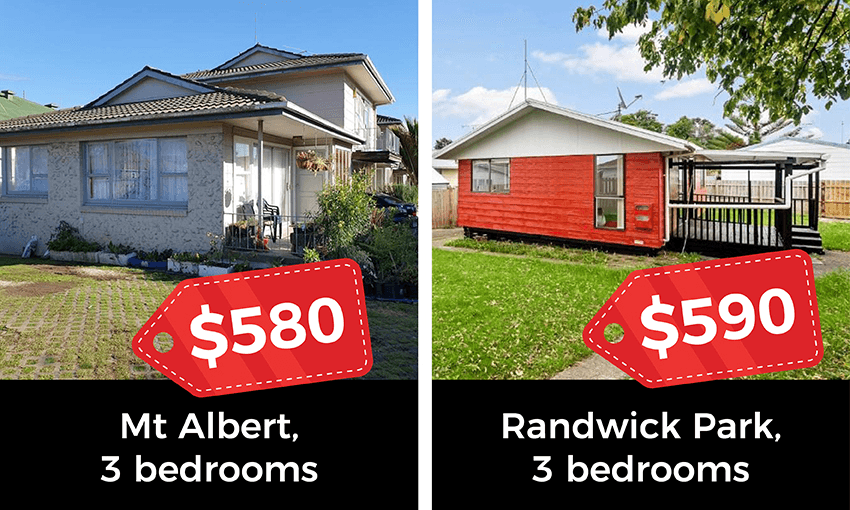

Despite South Auckland’s besmirched reputation, deserved or not, one aspect where it does roughly match the rest of the city is, surprisingly, in rent price.

The median weekly rent for a two-bedroom house in Mt Albert is $515, in Glenfield it’s $500 and in Onehunga it’s $500; while in Māngere Bridge it’s $550, in Ōtara it’s $505 and in Manurewa it’s $480. While I’m sure all these areas have their share of cold, damp rentals, what marks out these suburbs north of the Manukau Harbour is their proximity to good public transport, more quality recreational amenities, less violent crime, a hospital not known for poo running down the walls, and mid to high decile schools.

My own renting experiences in South Auckland have been mixed. The best house was a lovely two-storey townhouse, which had kind of a Spanish stucco villa vibe. The rent was in the high $500s, if I recall correctly, and apart from a suspected murder happening next door, and a few dodgy winos wandering past, it was actually a really nice, quiet neighbourhood. The worst one I saw was for a viewing. It was a cold, dark, carpetless former state house, with maggots crawling up the walls of the kitchen and rat shit throughout the lounge. A real “fixer-upper” for roughly $450 a week.

So why, when the region is known to lack many of the advantages of central and north Auckland suburbs, is our rent so high?

Dave Tims is a pastor and community worker and he’s called Randwick Park, neighbouring Manurewa, home for the last 10 years. He moved into the area a few years after a brutal shooting at a liquor store, and while there’s been a noticeable drop in crime, it’s still an area of many challenges. It has a median income of $22,600, the primary occupation in the area is labourer and the local schools are either decile one or two.

He says there have been a number of houses on his street recently advertised in the mid to high $500s, and the most recent was just next door.

“It’s a two-bedroom home, 66 square metres for $500 plus a week,” he says.

“We are not the flashiest street in Auckland. Our houses are poorly built and it’s an area known for its poverty, yet the landlords are charging huge amounts. But what’s surprised me most is that it’s just been one person after another, after another, coming to view it. People of all cultures and backgrounds, so it looks like there’s a real demand.”

Tims says the worst part is seeing longtime residents move out of the area.

“I had a neighbour whose landlord sold their house, but they really wanted to stay – because it’s such a well-connected street,” he says.

“Our street has its own Facebook page, we do street barbecues and everyone knows each other. So he checked out this other place for rent and there was just no way he could afford it.

“As far as I know, people are either moving up north or down to Huntly. Usually gentrification happens from the CBD and goes out. But we’re in Manurewa, we’re already on the edge, so what’s next? Gentrification has basically happened to the whole of Auckland and there isn’t anywhere else to go, unless you’re prepared to move out of the city.”

Auckland Action Against Poverty (AAAP) co-ordinator Ricardo Menendez works with many families facing eviction or struggling to pay their rent.

He feels gentrification is starting to happen in South Auckland at a scale not seen since the days when Pacific families were forced out of Ponsonby and Grey Lynn.

“We’re essentially seeing state-led gentrification, especially in places like Māngere, where a lot of development is happening,” he says.

“These developments have a history of driving house prices and rents up and Māngere has one of the biggest mixed tenure developments in the whole of the country, and the end result of this development will be an increase in rent prices.”

Menendez says if people can’t access financial support or increase the number of breadwinners in the home, they are just moving further south.

“These communities were already pushed out of Ponsonby and other areas, and now they are basically reliving this displacement and moving to places like Pukekohe, which for them is a whole different community.”

He says another element driving the high rents in these low-income areas is the subsidies provided through Work and Income.

“The accommodation supplement plays into it. It’s effectively a subsidy for landlords. From an AAAP perspective, our position is that to stop the reliance on the accommodation supplement, there needs to be a focus on building more public housing. The other option is to focus on lifting core benefits, as opposed to relying on supplements.”

Joanne Narayan has worked extensively in the property industry over the last 14 years, including nine years as a residential property manager in Manurewa, Clendon and Papakura.

She’s seen first-hand how landlords have been able to raise rents, despite their tenants being on really low incomes.

“Basically, the way I see it is a lot of people are able to access social welfare,” she says. “What I would see is if a landlord puts the rent up, the tenant would take the rent increase letter to WINZ and they would get topped up.”

Narayan says she would often ask tenants why they didn’t try to buy a house given they were able to pay such high rents.

“Given the type of housing in places like Clendon and Manurewa, the rent is definitely not worth it, and I would sometimes say to the tenants, ‘If you’re paying $600 in rent, you should be looking at buying something’, but they weren’t going to be able to get a mortgage. And families grew up in these areas, so they wanted to stay there.”

Child Poverty Action Group has provided extensive analysis over the years into what’s driving our housing issues, and most recently undertook an in-depth piece of research into the accommodation supplement.

CPAG’s housing spokesperson Frank Hogan says a number factors are driving the high rents in South Auckland. He says the government is decreasing the supply of private rentals by leasing large numbers of rentals for those on the social housing waiting list. He also believes there is less demand in other parts of Auckland for rentals, while in South Auckland demand is higher because families tend to be larger, so are able to pay bigger rents.

“The [main] reasons are fewer houses for the people needing them, plus overcrowding, plus crowding out by the government spending on leasing private rental housing,” Hogan says.

“It’s a vicious cycle that favours landlords over children and their whānau, a vicious cycle that successive governments have upheld with tax breaks for property investors.

“High rents increase overcrowding, which maintains high rents. High rents help increase social housing lists which are managed in a way which increases rents even further.”

However, Narayan does believe the recent tenancy law changes could lead to a number of property investors getting out of the market.

“The changes are good, because there’s now a disincentive for those who don’t comply,” she says. “It will be a lot harder for landlords, as they will feel like they have no control of their investment.

“The only reason you would have a rental now is that you want a long-term capital gain or something for your children, but for the smaller mum and dad investor, you’d have to think twice.”

Minister for Pacific Peoples and Māngere electorate MP Aupito William Sio says the passing of the Residential Tenancies Amendment Bill is just one of a number of measures his government has taken to address this issue, particularly for Māori and Pacific communities that make up a large proportion of South Auckland’s population.

“Part of the changes introduced include banning landlords from seeking rental bids and limiting rental increases to once every 12 months,” he says.

“When we came into government in late 2017, we started focusing on the housing development of Māngere as a priority… [for] building 10,000 new houses over a 10-15 year period. So I would be really keen to see the evidence that the Kāinga Ora developments are raising rents… and keen to have people raise those concerns with my office so I can follow up on it.”

He also highlights the $400 million Progressive Home Ownership Fund as a key initiative to help those on low to medium income, particularly Māori and Pacific families, into home ownership.

“As a government, we are making progress with housing affordability, we are committing to investing in housing and working hard on delivering solutions to enable more families to own their own homes and secure their futures.”

One Manurewa-based property investor Luella Linaker believes the responsibility to keep rents affordable also falls to those like herself, to take a more ethical approach.

“When we go to homes around Manurewa to look at homes, what we really want to do is find homes that our friends could live in, so they have a place that’s safe to live in for them and their kids, that’s warm and affordable,” she says.

“For me the ethical approach, is to have as much commitment to the people you are housing, as the property.”

Justin Latif previously worked as communications adviser for the Child Action Poverty Group