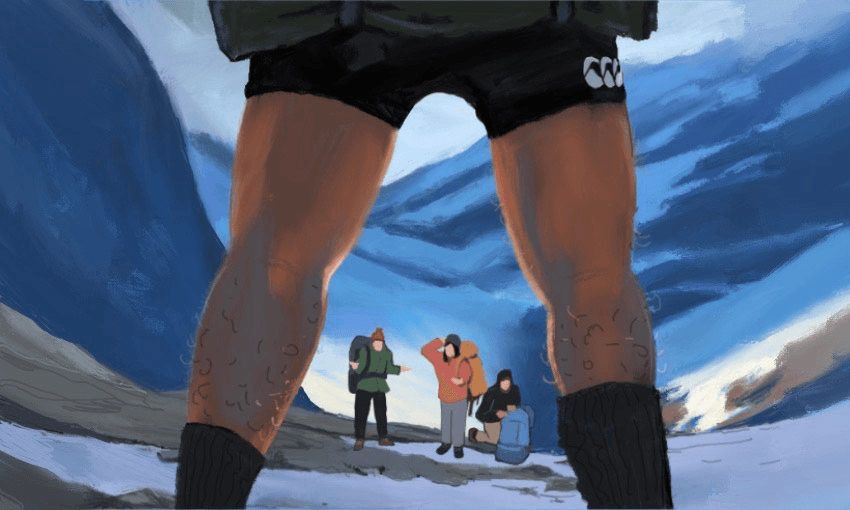

Even in the dead of winter, New Zealanders refuse to wear trousers to hike – and there’s practical and historical reasons as to why.

It’s fairly easy to spot a Kiwi tramper on an overseas hike. It’s not the rugby jerseys nor the mullets that out us – it’s the shorts.

Anywhere in the world, no matter the trail, New Zealanders can be seen ploughing through all kinds of abominable conditions in their stubbies. Last year, while hiking through India, “why are you wearing shorts?” came a close second to “where are you from?” as the question I was most asked by locals.

Once, when crossing a tick-infested field, I folded, and donned long pants to fend off bloodsuckers. The move felt wrong, like I’d abandoned some innate Kiwi-ness and become just another European: fashionable, formal, and sensitive to the cold.

Eric Van Hamsfeld is a keen outdoorsman. Since 1996, he’s tramped all over the South Island, enduring thick clouds of rain and sandflies. Like many Kiwi trampers, Eric balks at the idea of wearing long pants.

”We’re all brought up with shorts in this country,” he says. “I’ll wear shorts well into winter, and only when it gets really cold will I reluctantly put on trousers.”

Van Hamsfeld isn’t alone. Ben Kepes, managing director of Cactus Outdoor and Te Kuiti’s Ray Scrimgeor, DOC ranger of some 50 years, say they seldom choose pants.

“I wear shorts every day,” says Kepes. “It’s a central part of who we are. I think the feeling of freedom – of your legs being able to move and climb, unencumbered by stuff and free from wet fabric sticking to your legs – is just a great feeling.”

“There are times and places where long pants are appropriate,” adds Scrimgeor. “But all other things considered, shorts every day.”

It makes sense to wear shorts in New Zealand’s outdoors. Our wilderness is a critter-free Eden. Many of us walk barefoot without fear of ticks, leeches, and other pests.

Our Pacific climate is also mild but rainy, with a tempestuous high country that often sees four seasons in a day. If you go tramping, it’s almost certain you’ll get wet – and shorts tend to dry quicker than trousers.

Scrimgeor adds that shorts are essential for negotiating the rough terrain of our motu without snags and chaffing.

“Long pants and bulky wet garments can provide significant impediment to movement, especially when traversing steep and broken terrain,” Scrimgeor says, recalling his kit when hunting tahr in the 1970s and 80s.

“We would often be well clothed to keep our upper body warm […] but our lower half was often only clothed in a good pair of boots, socks and undies – even short shorts were often seen as an unwanted impediment.”

Yet, we’re not the only country with this sort of climate and landscape, and still New Zealanders appear unique in their devotion to free thighs – even down in the freezing south.

In this respect, our attachment to shorts seems cultural as well as practical.

“We’re an egalitarian country,” says Kepes. “There’s an aspect of cultural pride and identity that comes with that.”

New Zealand settlers prided themselves on living in an egalitarian country. In particular, New Zealand farmers distinguished themselves from their British forbears by abandoning the latter’s strict attitudes towards status, formality – and proper dress.

From the time of Te Tiriti o Waitangi, Pākeha were often regarded as rough colonials with classless fashion. In the 19th century, New Zealand had few tailors, meaning rich and poor alike had to make do with a slim variety of hardy clothes, made specifically for the outdoor work almost everyone engaged in.

Still, despite our egalitarian tilt, wearing shorts in public seemed beyond the pale. European manners were clear on this: bare legs were the preserve of barbarians, children, and the morally defunct.

In the backcountry, things were different. While most period photographs show proto-trampers in formal clothes until the 1960s, records suggest other New Zealanders – specifically soldiers – had freed their knees.

“After 1868, practically all the military forces in the field left their trousers in barracks and took the bush trail wearing the waist-shawl, like the Māori rapaki,” wrote journalist James Cowan, who started reporting in the late 1800s.

Cowan writes that soldiers, when bush travelling, found kilts and Māori garments “capital fashion for rough work, particularly river crossing in such places as the King Country”.

Māori clothing reveals centuries of adaptation to the country’s wilderness. Flaxen kilts like the rāpaki and piupiu keep legs uncovered. Māori understood that, in the backcountry of Aotearoa, keeping dry and mobile was the best defence against cold.

Still, despite the benefits, polite society forbade bare legs. It would take a global crisis to bring stubbies out of the bush and into the mainstream.

In the Second World War, shorts became standard issue for ANZACs serving in North Africa. The British had caught on to “Bombay bloomers”, a knee-length and baggy make of shorts from India, where monsoon humidity turned panted-legs into pressure cookers.

These bloomers were a long way from today’s stubbies, but they nonetheless encouraged Kiwi troops to consider short pants acceptable garb.

After the war, returned soldiers didn’t want to put away their shorts. They were too breezy, too comfortable, and too freeing – especially in the heat.

Trade unions petitioned the government to permit civil servants walk shorts in “hot humid climates such as Napier, Gisborne, Auckland and Whangarei.”

The State Service Commission relented, on the condition that short-wearing male officers “are working away from the public”.

This concession was the sharp end of the wedge. As state officials donned shorts, workers across the motu successfully lobbied employers for a similar dress code. New Zealand had liberated its thighs.

“I have these images from my childhood of farmers, trappers and pighunters,” recalls Scrimgeor. “In the 1960s, that ‘bush shirt and shorts’ look became pretty iconic.”

Comedian John Clarke would seize upon this look to create the character Fred Dagg, an uncouth, rough-as-guts farmer sporting gumboots, a black singlet, floppy hat and – of course – shorts.

Dagg’s stubbies are now on display at Te Papa. They represent one of the first times rural New Zealand recognised themselves in popular culture. Clarke’s character oozed ambivalence to polite society and ideas of class. He also looked tough.

That’s another value New Zealanders project when they don shorts in winter: toughness.

Kepes, who’s been in the business of producing outdoor gear for three decades, says this quality is essential to our backcountry style.

“Think about hiking in Europe, you walk up a mountain and there’s a cafe with full-cooked meals at the top. You’re hiking in the Tararuas… it’s rugged and it’s hard.”

“We’re a hardy country. We’re a hardy people… we need equipment that comes with that hardiness.”

Yet Scrimgeor thinks these attitudes, and our attitudes towards shorts, could change.

“Modern lightweight synthetic fabrics have done away with many of [long pants’] disadvantages, and I can see more and more outdoors people using these lightweight easy-care garments,” he says.

Cultures and values shift with time. As shorts came into vogue last century, they could just as easily leave. Moreover, as new hikers hit our trails, their influences might not be their stubbie-clad, bush-bashing parents, but American influencers – clad in long pants.

Still, Van Hamsfeld swears he’ll never pant up on a trail, however fashionable and slick the new gear may be.

“We’re not here to look good,” he says. “We’re here to achieve.”

Update: This article originally called shorts skivvies a few times. The author considers himself rightly corrected and has changed these mentions to stubbies.