Internal affairs minister Tracey Martin has announced that legislation that would allow transgender people to more easily change their sex on birth certificates will be deferred following concerns around changes made by the select committee which, said Martin, ‘occurred without adequate public consultation’, creating ‘a fundamental legal issue’. The decision, widely deplored by the trans community, follows a sustained campaign by gender critical activists. In a feature originally published earlier this month, RNZ In Depth reporter Susan Strongman looked at the proposed law change, and the heated debate around it.

Georgina Blackmore meets me in an Auckland park. The air is thick with humidity and her blue chiffon headscarf flaps in the wind like a hooked fish. Blackmore – who is tall, about six foot, and softly spoken with a slight English accent – doesn’t want her job, even the area in which she works, mentioned in this article. “I have had friends get lobbied out of their jobs over this issue and I really need mine.”

“This issue” has made the 37-year-old intensely hated by some people. She recently received a rape threat online. She says such threats are nothing new. She’ll report it to Netsafe, and expect nothing to come of it.

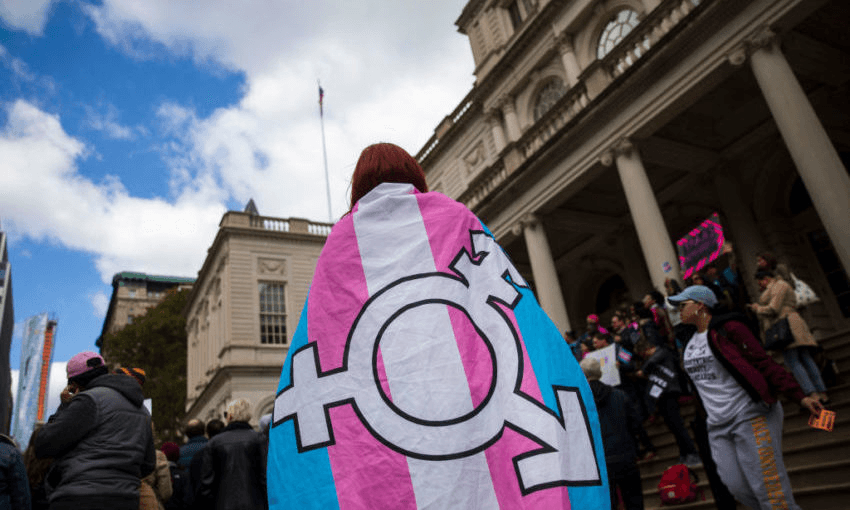

Blackmore is the target of hatred, anger and threats of violence because of her stance on the rights of transgender and gender diverse people in New Zealand. The “issue” to which she refers is a proposed law change that will allow gender diverse people to more easily change the sex on their birth certificate. Blackmore, who calls herself a gender-critical feminist, heads the group Speak Up For Women, which is pushing back hard against the change. She wants wider public consultation on the Births, Deaths, Marriages, and Relationships Registration Bill, because she believes it will put women and girls at risk.

But, spend time with some of the gender diverse people on the other side of this argument and they will tell you about the hatred, anger and threats of violence they’ve endured for being themselves. It’s they who are at risk, they’ll tell you. They need this law change.

At present, there are myriad hoops a person must jump through to change the sex on their birth certificate – usually including an application to the Family Court providing proof they’ve had medical treatment to transition. This is at odds with the process for changing a New Zealand licence or passport, which is done by statutory declaration – a document completed in front of an authorised witness like a lawyer or Justice of the Peace.

In August last year, following a petition to parliament, amendments to Minister of Internal Affairs Tracey Martin’s Births, Deaths, Marriages, and Relationships Registration Bill were recommended by parliament’s Governance and Administration Committee. One of the recommended changes will mean a statutory declaration will be all that is required for a person to change the sex on their birth certificate to male, female, intersex or X (unspecified).

The changes will bring New Zealand law into line with countries like Ireland, Malta, Colombia, Norway, Denmark and Argentina, where similar legislation is in place. The second reading of the bill is scheduled for early this year.

Proponents of the change – people like Jack Byrne, who has a background in policy and human rights, and is transgender – say it will meet the need for gender diverse people to have gender affirming documentation and recognise international human rights law, but it isn’t going to affect many people. The Law Society notes in its submission to parliament on the bill that for many people, engaging with the Family Court is stressful and intimidating. Applicants also typically need legal representation, the cost of which can be prohibitive.

In an anonymous submission to parliament, the parents of a transgender teen write that their child’s “future well-being and safety depends on their ability to move about, freely and legally, within New Zealand and in the wider world,” and that the legal recognition of their correct gender would mean they were better protected by New Zealand law when they travel to other countries and in education and employment. “Knowing that the law sees them the same way they see themselves was important to us in that they would be able, without fear, to attend school and later be in employment as their lawful gender.”

The parents, who navigated the current process to change their teenager’s birth certificate, estimated they spent 40 hours writing, and lodging documents to do so. The process also required four trips to the Family Court, two to a Justice of the Peace, and one to a GP. All up, they say it took 18 months to make the change. They tackled the court system as laypeople, saving what they estimated to be $5000 in lawyer fees, and say over the years they’ve spent at least $12,000 on medical treatment, including psychologist sessions, with their young person.

But Georgina Blackmore is convinced any benefits of the changes will be outweighed by dangers. On the Speak Up For Women website, an open letter to all members of parliament says “self-ID has significant potential and unintended consequences for women and girls.” The letter lists concerns relating to laws that allow spaces and institutions like changing rooms, girls’ schools, women’s shelters, Girl Guiding and women’s prisons to be single-sex; the collection of statistics; and access to female-only scholarships, quotas and sports teams. It has been signed by 506 people.

Signatories include parents, teachers and medical professionals who have articulated fears about the implications of the law change that are raw: A teacher from Ngaio worries it might attract to women-only spaces “men who, with self-ID, can identify as women, but appear still to be men.” Another fears there would be no way to stop a man with a known history of sex-offences against women from changing sex on his birth certificate and approaching women in public toilets. A father worries about the safety of his daughter, his partner, his mother and friends: “Literature shows trans women retain male levels of violence,” he writes. “It’s about keeping female spaces safe for females.” A signatory who calls themselves “MS” worries about women having to compete against “male bodied” people in sport, while a 22-year-old film student, and “VF” of Te Tai Hauāuru both raise concerns about the medical transitioning of young people, particularly lesbians. “Children who are too young to understand what sex and gender are, are being assisted to transition medically and irreversibly before they can consent,” VF writes. A GP, mother and grandmother of girls, submits that anyone who thinks the proposed law will not be abused is “breathtakingly naive”.

Byrne, who changed his birth certificate via the Family Court in 2009, says he’s saddened by this. “The backlash has turned something that will make a really big difference in some situations where [gender diverse] people are particularly vulnerable – including kids – into what feels like a retrogressive debate about which bathrooms trans people can use.” He calls some of the reaction from the bill’s opponents a “cesspool of harmful stereotypes,” which presents trans people as deceptive, fraudulent and predatory.

Indeed, the dialogue between some of those concerned about the impact of self-ID laws on cisgender women, and those who support the proposed changes has become increasingly toxic. Online, some gender critical activists use misgendering and deadnaming to abuse gender diverse people. (Banned under Twitter’s Hateful conduct policy, misgendering is using the incorrect gender to refer to a person and deadnaming is using the name a person had prior to their transition, with the intention of undermining or denying their identity. In the last few months alone, supporters of Speak Up For Women on Twitter have called Wellington woman Caitlin Spice a man, a bloke, “a male who thinks he’s a lesbian”, and a misogynist.) Women’s Refuge staff members also say they have been harassed – in one case by a Speak Up For Women supporter pretending to be a journalist. Meanwhile, those who raise concerns about the effects of the change are often accused of transphobia or called terfs (once a simple acronym, short for ‘trans-exclusionary-radical-feminist’, terf is now used by those who disagree with gender critical feminist ideology as a slur. Blackmore calls the term “hate speech” which is “used to belittle and threaten anyone who rejects the premises or conclusions of transgender ideology” and to “dehumanise and incite violence.”)

Though the concerns raised by signatories of the open letter may be genuinely-held fears rather than deliberate attempts to harm gender diverse people, most appear to be misguided. Police say they are “not currently aware” of any trend of men dressing as women to access female-only spaces like bathrooms, changing rooms or safe houses (birth certificates are not a requirement to get into those spaces anyway). The head of the New Zealand Women’s Refuge national collective, Ang Jury, says there is a solid process around deciding who gets into safe houses, and that transgender women have been allowed into many refuge spaces for years without issue.

Statistics New Zealand’s Dean Rutherford, who is responsible for most of the statistics the agency produces, says he doesn’t expect the law change to have “any impact at all”, and Simon Denny, an associate professor and paediatrician at the Centre for Youth Health in South Auckland and University of Auckland rejects the suggestion that transgender women retain male levels of violence, or that a parent could pressure their unwitting child into transitioning to the opposite sex (“No. Absolutely not. Because they have to go through us. It couldn’t happen.”)

Recent claims in the media that children as young as five are given sex hormones and puberty blockers have been corrected (children are not given puberty blockers until the onset of puberty) and claims that a high percentage of children with gender dysphoria will “grow out of it”, often made by conservative groups like Family First, are not credible (an outdated report on the Ministry of Health website quoting research estimating “75% of transgender children would not go on to identify as transgender adults” has been taken down; “There is now more understanding of the complexity of the spectrum that is gender identity and how this is expressed,” Counties Manukau Centre for Youth Health clinical lead Dr Bridget Farrant says.)

Meanwhile, transgender athletes have been struggling to compete in sports as the gender they identify with for years, with or without gender confirming birth certificates.

Feminist academic and University of Canterbury School of Law Professor Elisabeth McDonald says there are very few laws where we make differentiations on the basis of sex. Where we do – like under the Human Rights Act, which makes exemptions for single sex prisons, schools and sports teams – we already accommodate people who have changed the sex marker on their birth certificate through the Family Court. McDonald doesn’t believe that a law change will erode the protections these spaces grant women. “I really don’t think we will notice a difference. The world will not stop. Women will not be less safe.”

In 1989, at Tauranga hospital, a healthy baby was born. The baby’s parents named this squirming wee bundle Jessica. Hospital staff ticked a little box on a piece of paper that marked Jess as female. That little baby grew up, went to school, university, got a job, married, and had a baby of their own.

It still says ‘sex: female’ on Jess Mio’s birth certificate, but it makes Mio feel like a fraud. Mio is non-binary – neither male, nor female. But six months into an attempt to change the ‘F’ to an ‘X’, to bring it into line with their passport and driver’s licence, Mio’s birth certificate still says female.

The need to have documentation confirming one’s gender is not something many people have to think about. If you are cisgender – meaning your gender corresponds with the sex you were assigned at birth – it’s unlikely you’ve ever been asked to show your birth certificate or passport as proof of gender, or if you have, it’s not been a problem. But for members of our transgender and gender diverse communities – people like Mio – having gender confirming documentation could help keep them safe from the persecution and violence they are so often the target of.

Jack Byrne says that if people aren’t able to be recognised before the law, it makes them vulnerable to not being protected by that law. Someone without a birth certificate confirming their gender identity is at risk of being outed as transgender, in situations where they may not want to be – opening a bank account, enrolling a child in school, applying for a student loan or where a pre-employment police check is required. “It’s about things like being able to go to school, or being able to get a job,” Byrne says. “Even though it may feel like it’s just about registering details on a certificate.”

In 2008, the Human Rights Commission’s report on the discrimination of transgender people in New Zealand found that having consistent documentation could affirm a trans person’s gender identity and dignity, form an important part of the process of transitioning, and help solve the problem of incorrect documentation undermining one’s identity and being a constant reminder that their sex and gender identity are seen as being incongruent.

Yet more than a decade later, it took Mio three months to get even a response from the Births Deaths and Marriages Office about what evidence they needed to make the change. They presented evidence from their GP and were told it was insufficient, but they were given no information as to what would be sufficient. Eventually, the office apologised for their delay and asked for further information from Mio’s GP and from the hospital where Mio was born.

For Mio, the thing that makes it clear that their birth certificate is wrong, and that their gender is not female, but indeterminate, is that Mio says it is so: “Like, I’m here, I’m alive. I’m telling you this is wrong.”

Wellington mother of two Sharyn Forsyth is exasperated by the misinformation swirling around the law change, and knows her 17-year-old son Jack sees some of the dialogue being used by gender critical feminists, transphobes, and conservative Christian groups online. She worries about the effect it has on gender diverse young people. Forsyth coordinates a group for parents and caregivers of transgender and gender diverse children, which is currently made up of about 280 families. “The teenagers that I know through the group, invariably, are struggling with society and struggling at school, as opposed to, you know, finding that ‘hey life is great and I have this great big horde of friends and I’m admired’,” Forsyth says.

Gender critical feminists often raise concerns about the number of young people medically transitioning, citing a study of referrals to Wellington Endocrine Service, which shows an increase in the number of transgender people referred for treatment, particularly among the young adult age-group (20 to 30-year-olds.) The study’s authors speculate the increase could be the result of greater awareness and acceptance of gender diversity, and access to global gender diverse communities via the internet.

Associate professor Denny says similar increases are being seen globally. Though the proposed law change is unrelated to the transitioning of children (or adults), one submission broaches the subject anyway, suggesting that the increase is due to parents pushing prepubescent children onto puberty blocking drugs, and adolescent youth on to sex hormones. And late last year, a NZ Herald columnist suggested that “parents, wanting to be best friends with their kids, are taking their son’s fixation with dolls as evidence that he’s really wanting to be female,” also hinting, perhaps, that the increase could be related to parental pressure.

But Forsyth says any suggestion that a parent would push their child into transitioning is absurd. “There seems to be this perception, particularly for the younger ones, that parents are out there going ‘oh whoopee, I’ve always wanted a little girl or a boy’, and are therefore going to force their child [to transition]. No one would want their child to be transgender knowing what it is going to mean in terms of society’s judgement. It doesn’t make life easier. There is this myth out there, particularly with teenagers … that that’s the latest cool, trendy fad.”

Based on her personal experience, Caitlin Spice, who transitioned in 2007, agrees with Forsyth’s sentiment: “I never asked to be trans. I never wanted to be trans. It’s awful, it’s not something I’d wish on anyone else, and I hate being reminded of that by people trying to make things harder for us.”

Forsyth says the main thing that transgender young people want is to live normal, happy, healthy lives. But if their birth certificate has the wrong gender on it, she says, they’re “continuously outed to providers, teachers, whoever.” Her concerns about trans children being outed are, sadly, a reality for many gender diverse young people and their parents; the Youth’12 survey found that trans young people were four and a half times more likely to be hurt or bullied at school at least weekly. Half of trans youth reported being hit or harmed by another person (compared to 33 percent of cisgender), more than half were afraid that someone at school would hurt or bully them and one in five trans students had attempted suicide in 2011. “We’re fortunate that there are a few who have transitioned early on that you know they fly under the radar and they succeed. But the far greater majority you know don’t find life at all easy,” Forsyth says.

It’s not just children who are at risk if they’re outed. Jack Byrne, who is currently working as a researcher on Waikato University’s Aotearoa NZ Trans and Non-Binary Health survey, Counting Ourselves, says the levels of violence reported in the survey, which will be released later this year, is sobering. Byrne also knows people who’ve experienced violence first hand; “I have trans and non-binary friends who have been physically or sexually attacked on the street, in public bathrooms, and in their own homes, because of their gender identity or expression. Many people from our communities have fears for their safety.”

Georgina Blackmore agrees that there is misinformation swirling around in the debate over self-ID law, including among some of those who have signed the open letter on her website, (“I think people can fixate on certain issues”), but stands firm in her belief that simplifying the process of changing gender on one’s birth certificate will put women and girls at risk.

“Self-declaration [self-ID] is not a new concept. It’s something that has been predicated overseas, so we’re benefiting from looking at overseas implications.” What implications? Blackmore points to an instance in the United Kingdom (where self-ID laws are yet to be passed and an often toxic debate over proposed reform of the Gender Recognition Act is currently raging) where transgender female prisoner Karen White, a convicted pedophile who was on remand for grievous bodily harm, burglary, multiple rapes and other sexual offences against women, was placed in a women’s prison and sexually assaulted two inmates. White’s placement was seriously mismanaged by the UK’s prison system, and Blackmore worries a similar thing could happen in New Zealand’s Corrections facilities, where in January 37 of approximately 10,000 inmates identified as being transgender (32 of whom reside in men’s prisons).

Under Corrections’ policy for the treatment of transgender and intersex prisoners, which rolled out in March last year, transgender prisoners can apply to be placed in a prison holding inmates of the gender with which they identify. The policy makes it clear that those serving a sentence for serious sexual offences against a person of their nominated sex are not eligible to be moved to a facility housing prisoners of that sex. This means that a prisoner like transgender woman Morgana Platt, who has previously been jailed for raping and sexually violating a 16-year-old girl and is currently serving time for sexual exploitation, would not be placed in a women’s prison.

But, among other things, Blackmore is concerned about a section of the policy that appears to be an exception to this rule. The section states that prisoners who present a birth certificate specifying their sex must be placed in a prison with inmates of that sex. “So if you bring in self identification, they would fill out a statutory declaration form … they would be automatically rehoused,” Blackmore says. She worries that this will allow people like Platt, regardless of prior convictions, to be moved to women’s prisons where inmates are vulnerable and have often been victims of sexual assault and domestic violence.

Could this also mean that if New Zealand passes the proposed self-ID law, a potentially dangerous cisgender male could “game the system” to access a women’s prison, or a trans woman like Morgana Platt could change her birth certificate and be rehoused alongside vulnerable women, regardless of Platt’s past offending? Blackmore says she doesn’t want to judge all transgender women for the actions of a few, but believes Corrections needs to create a robust policy to keep all prisoners safe.

But is Corrections not already managing violent behaviour by people of all genders in its prisons? When asked about the potential impacts of the bill, Corrections emailed a statement which said it was “considering the potential impact of the bill on our operations to ensure that our processes uphold the safety of all of the prisoners in our care”. Documents show that when a transgender prisoner is moved, Corrections staff decide whether the prisoner is at risk or if they pose a threat to other prisoners, and whether segregation is required.

The Department of Internal Affairs has reviewed evidence in countries where self-ID laws are in place and found no evidence of prisoners trying to “game the system” to access prisoners of the opposite gender. It also advised that Justices of the Peace, and other witnesses to a statutory declaration are “well placed to assess the credibility of a person” and are able to refuse them if they are not satisfied the declaration is correct. In addition, making a false statement is an offence punishable by five years’ imprisonment, and the proposed process for self-ID provides for only one change of sex – meaning a person trying to “game the system” will be permanently stuck with a birth certificate showing the incorrect sex.

In advice on the bill given to the select committee, Internal Affairs said it did not think the changes would increase any risk of offending by transgender prisoners against other prisoners.

In Malta, where self-ID has been in place since 2015, prisoner placement is dealt with on a case-by-case basis: “A male-to-female inmate living as a woman should be allocated to a female establishment as per gender marker. She should not be automatically regarded as posing a high sexual offence risk to other inmates and should not be subject to any automatic restrictions of her association with other inmates. The director reserves the right to assign a different allocation if there is clear evidence that the inmate may pose a risk of abuse or be subjected to abuse.”

What Jack Byrne likes to remind people is that the Births, Deaths, Marriages, and Relationships Registration Bill is about making it easier for gender diverse people to be legally recognised, and live their lives. It’s not about prisoners, sports, bathrooms, or children transitioning. And, he says, it’s not taking women’s rights away.

In 2008, five and a half years after Byrne transitioned, his father died. Byrne was still in the process of changing his birth certificate through the Family Court, and the sex marker still said ‘female’. His brother, who was filling out details on his father’s death certificate, asked him what what his legal name and sex was. Byrne lied to him. “There was no way I wanted to have female written beside my name… It was a couple of days after dad died. Those circumstances are very raw. I’m just really grateful he didn’t push me to show him the incorrect document.”

When Forsyth’s son Jack transitioned, the family put a birth notice in the Herald.

FORSYTH. Jack Kieran Marshall Forsyth – He’s got perfect hair and big brown eyes; he’s created excitement you can’t disguise; he’s a wonderful boy from an awesome pair, and that’s reason enough for a great fanfare. In 2001 with the best intentions we announced the arrival of a baby girl; with much joy and love we now correct our mistake and present our amazing boy, and hope to get more sleep than we did first time around – Sharyn, James and sister Mary.

Jack Forsyth is yet to change the gender on his birth certificate. His mum calls the Family Court process “lengthy” and “a barrier”, which comes with a lack of certainty around the outcome. It also requires detailed medical information, which could be considered intrusive to some. But Forsyth says if the law is passed enabling Jack to change the gender on his birth certificate by self declaration, it won’t affect anyone but Jack. “If this changes the ability to actually be able to declare their gender identity and say ‘this is who I am’, and it’s going to help them maintain the psychological safety, then I’m all for it.”

For support and information

Parents of gender diverse children can email nzparentsoftransgenderchildren@gmail.com

For more information on gender diverse communities, visit Gender Minorities Aotearoa

OUTLine, 0800 688 5463, is a free and confidential helpline for people wanting to talk about sexuality, gender identity and diverse sex characteristics. Calls are answered by volunteers 10am to 9pm weekdays, 6pm – 9pm weekends.

1737 – Need to Talk? Free call or text 1737 any time to speak to a trained counsellor, for any reason.