A new app seeks to simplify the complexities around sex, consent and what is or isn’t allowed during intercourse. Law professor Simon Connell looks at the implications of LegalFling.

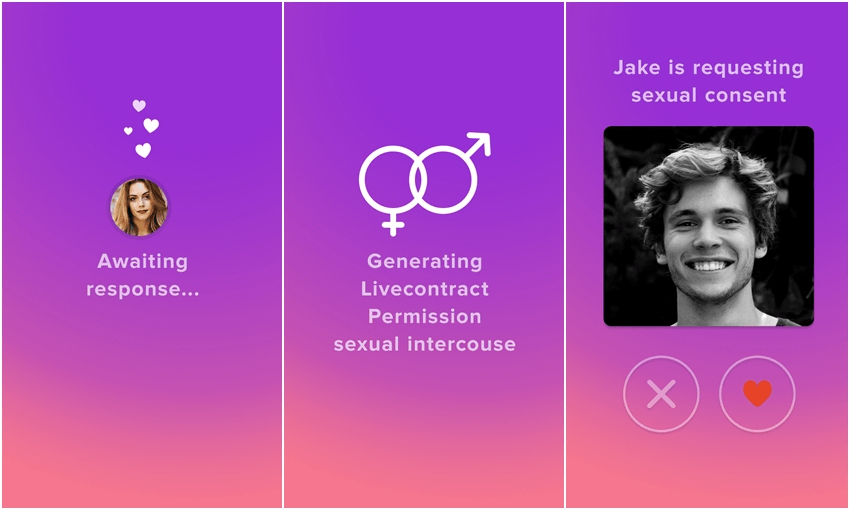

It seems that there’s an app for everything these days. Cue Dutch company LegalThings, whose app called LegalFling purports to solve the tricky problem of sex and what has and has not been consented to by the participants.

The basic idea is that it allows two (or more?) people to record their consent to sexual contact, including details like whether or not condoms are required, whether explicit language (vaguely defined as “language that may be considered offensive”) can be used, and whether BDSM and photo/video recording is OK.

There are a bunch of different things people might say or think about this app. The director of the anti-domestic violence charity Shine, Jill Proudfoot, has expressed her fears that it could be used by sexual predators to create evidence of “consent” which then is used as protection against later allegations of sexual assault. That seems a very real concern to me.

But what particularly piqued my interest as someone interested in contract law is the claim on the app’s website that it creates a “legally binding agreement”. This claim is repeated several times, such as (emphasis added):

“Sex should be fun and safe, but nowadays a lot of things can go wrong. Think of unwanted videos, withholding information about STDs and offensive porn reenactment. While you’re protected by law, litigating any offenses through court is nearly impossible in reality. LegalFling creates a legally binding agreement, which means any offense is a breach of contract. By using the Live Contracts protocol, your private agreement is verifiable using the blockchain and enforceable with a single click.”

and later, with a bit more qualification:

“The application generates a Live Contract, which is a legally binding agreement. Just remember, the app is about setting clear rules and boundries, not breaking them. To which extent the contract holds up in court depends on your country of residence.”

I’m interedted in whether the so-called “contract” might hold up in court as a contract in New Zealand. I say “as a contract” because (i) I don’t really know enough about criminal law to comment on whether it would hold up in court as evidence of consent (see here for a discussion focused more on the criminal side of things); and (ii) the claim that a LegalFling agreement is a contract is key for some of the other claims made on the website, namely:

Fully protected: Took a spicy video or photo? You don’t want that to go viral! With LegalFling any leaking of footage is a breach of contract and easy to take to court.

and:

Penalty clauses: Escalate a breach with a single tap, triggering Cease and Desist letters and enforcing penalty payments.

For present purposes, I don’t think the use of Blockchain or Live Contract technologies is especially significant, despite Blockchain being pretty trendy at the moment. Basically, it just means that the agreement is recorded externally (so one party can’t disavow all knowledge of it by altering the information stored on their phone) and that some steps can be automated.

Before I look at LegalFling specifically, I need to briefly talk about contracts generally – what follows is about the law in New Zealand and is necessarily an oversimplification.

A contract is basically an exchange of promises about the satisfaction of expectations about future performance (for example, “I agree I will build you a house”) and the state of any property being transferred (for example, “the house I am selling you is not leaky”).

For a contract to be legally binding, the law normally requires the following four things:

- Agreement: The parties to a contract must have both agreed to it. Often this is demonstrated by showing that one party made an offer and the other one accepted it.

- Certainty of Terms: The essential terms of the contract (ie the important details of what the parties have agreed to) must be clear. If some vital part of an agreement is unclear, there is no legally binding contract.

- Intent to Create Legal Relations: The agreement must be one that both parties intend to be legally enforceable. That is, the parties both want an agreement where they can sue each other for breach of contract if things go wrong. Examples of agreements that are not intended to be legally enforceable are so-called gentlemen’s agreements and non-serious agreements between family members.

- Exchange: For an agreement to be a contract, it must feature an exchange of promises between the parties. That exchange creates the contractual obligations that the parties owe each other. This requirement is called “consideration”, although that word isn’t very helpful in terms of explaining how the law works. Agreements without consideration (for example, I promise to do something for someone and they agree without promising anything in return) are not contracts and, while they might be enforceable, they are not enforceable as contracts.

If a party to a contract fails to deliver on what they’ve promised, then this is a breach of contract. The normal remedy for breach of contract is an award of damages to make up for what the innocent party has missed out on because the other party has broken their promise – at least as far as we can do so by making the breaching party pay the innocent party money. For example, if someone has promised to quickly deliver a vital piece of machinery for my factory and fails to do so, I might be able to get damages for the profits I’ve lost while waiting for the component to arrive.

This is a big deal because these damages based on trying to give you something you expected but never actually got can get quite expensive for the breaching party and are not the standard outside of contract law (for example, in the enforcement of agreements that are not contracts).

There’s a whole lot of law on how to work out how the court should put a dollar figure on a particular broken promise, and what the limits are on expectation damages. It’s rare for a court to actually order someone to do something that they promised as opposed to paying money.

OK – so how does that general law on contracts then apply to what LegalFling is trying to do?

The app probably satisfies the requirements of “agreement” and “intent to create legal relations” required for a binding contract. One person initiating a fling request and the other accepting it is pretty close to a normal offer and acceptance. And, the point of using the app is to signal an intent to create a legally binding contract.

However, it’s less clear whether certainty and exchange are satisfied. This is mainly because it’s had to work out from a legal point of view what the terms of the agreement are or, put another way, exactly what promises are being exchanged. I couldn’t find the text of the agreement online, so I have to speculate.

What I’m sure of is that LegalFling cannot be understood as an agreement to have sex (“we agree that we will have sex”). The FAQ states:

Can I still change my mind?: Absolutely. “No” means “no” at any time. Being passed out means “no” at any time. This is explicitly described in the agreement. Additionally you can withdraw consent going forward through the LegalFling app with a single tap.

So, what is the substance of the agreement? I think the idea seems to be to generate a conditional agreement, for example:

“If we have sex, we agree that condoms will be used and there will be no BDSM.”

A breach of those conditions would constitute a breach of contract. Put another way, both of the parties agree to refrain from certain behaviours during sex. In the case where none of the specific requirements have been selected, it’s a little more difficult to identify what the parties are actually agreeing. It can’t be “if we have sex, we agree that it will be consensual” because that would undermine the ability to say no at any time. So perhaps it’s something like:

“We agree that we will only have sex as long as both parties consent.”

In the abstract, this seems like a promise that people could exchange. However, there’s a bit of a problem: the obligation not to have sex with someone without consent does not depend on the presence of a contract. Respecting the bodily and sexual autonomy of other people is a requirement of being a decent human being. It’s also, you know, required of us by the criminal law, and furthermore, battery (touching another person’s body without consent) is a civil wrong that you can already sue someone for. There’s a risk here that the app might cause confusion over the law that we already have, for example, it’s a criminal offence to make intimate visual recordings without consent.

With respect to consideration, we have the slightly odd situation where the thing being promised under the contract is already something that we are already legally obliged to do. Where parties have promised to do something that they are already supposed to be doing, courts have sometimes found that there is no consideration because the parties have not actually taken on any new obligations as a result of the agreement. This is especially likely where it would be generally undesirable for the obligation to be enforced contractually – as is the case with LegalFling, I think.

Even if the LegalFling agreement were to satisfy the requirements of contract formation, some issues arise about how the promises would actually be enforced. There’s no obvious answer to how a court should, for example, put a dollar value on the breach of an obligation to not incorporate elements of BDSM into sex. Since contract remedies are usually based on expectations, the remedy would arguably not only reflect the invasion of bodily autonomy but the absence of any satisfaction that would have been gained from BDSM-free sex.

LegalFling may think they have pre-emptively addressed this problem: the parties can trigger penalty payments for breaches of contract. Presumably, this means that the parties can specify dollar values for certain breaches – let’s say $500 for use of explicit language during sex, or perhaps the dollar amount comes standard.

I can see several problems with this. First, the list of penalties might be seen as a price list and incentivise breach for those who can pay. Second, it potentially falls foul of a legal doctrine called the “rule against penalties”.

This rule is complicated and the current state of it is rather unclear (some judges in the UK Supreme Court described it as “an ancient, haphazardly constructed edifice which has not weathered well…” (Cavendish Square Holding BV v Makdessi [2015] UKSC 67 at [4]). I won’t get into the detail of it here, but the current law is something as follows.

Just because the parties have specified a dollar amount for a particular breach doesn’t mean that a court has to enforce it. Courts will give effect to clauses that compensate for the failure to satisfy the expectations raised by the promises made in the contract. However, courts will refuse to enforce clauses that go beyond that and punish the breaching party. Whether or not the agreement calls a contract a “penalty” is not decisive.

Because the sort of conduct that would constitute a breach of the LegalFling agreement is both (i) an intangible loss that is hard to put a dollar figure on, as I discussed earlier, and (ii) generally going to be the sort of behaviour that many people might think deserves punishment, I would suggest that there is always going to be some doubt over whether any “penalty clauses” in the LegalFling contract are actually enforceable.

So LegalFling’s makers’ suggestion that they are creating a legally enforceable contract seems highly doubtful. First of all, considering what actually is being promised means that the agreement might fail to satisfy the requirements for the formation of a legally binding contract. Second, even if the requirements for contract formation are met, problems arise in working out what damages would be payable, and any “penalty clauses” set out in the contract might not be enforceable because of the rule against penalties.

Finally, I can think of no good reason why dealing with issues of sexual consent through contract law proceedings is desirable at all. There might be some merit in an app that facilitates discussion about what people are and aren’t into (which should be happening anyway and hardly requires an app) – but that’s not LegalFling.

This section is made possible by Simplicity, the online nonprofit KiwiSaver plan that only charges members what it costs, nothing more. Simplicity is New Zealand’s fastest growing KiwiSaver scheme, saving its 10,500 plus investors more than $3.5 million annually. Simplicity donates 15% of management revenue to charity and has no investments in tobacco, nuclear weapons or landmines. It takes two minutes to join.