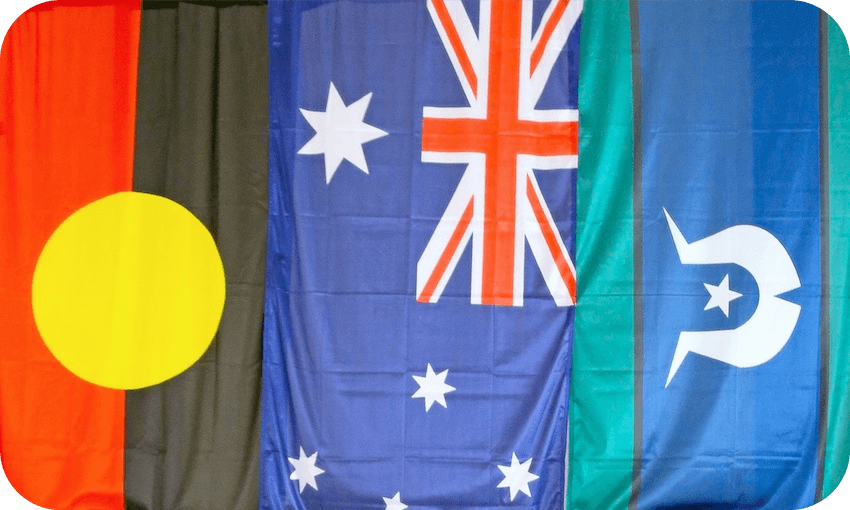

A divided Australia will soon vote on the most significant referendum on Indigenous rights in 50 years.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised this article contains names and/or images of deceased people.

Australian prime minister Anthony Albanese has announced an October 14 date for a national referendum on whether to amend the Constitution to establish a new advisory body for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Called the “Voice to Parliament”, the new body would provide advice and make representations to parliament and the government on any issues relating to First Nations people.

The Voice to Parliament has been toted as a vital step toward redressing Australia’s painful history of discrimination against Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

The minister for Indigenous Australians, Linda Burney, has said it would also remedy a “long legacy” of failed policies on a variety of issues, from the over-representation of First Nations people in the prison system to poorer outcomes for First Nations people in health, employment and education.

The Voice represents a new approach. Initially proposed in a document called the Uluru Statement from the Heart following a First Nations constitutional convention in 2017, the Voice would be enshrined in the Constitution to ensure it would have a permanent presence and role in Australian government.

This is why a referendum is needed – and why this particular one has been so fiercely debated for years.

Decades of efforts toward equality

In order for a constitutional referendum to be successful, it must garner a majority of votes nationally, as well as a majority of votes in a majority of states (this means four of the six states). Votes in Australia’s two territories – the Australian Capital Territory and the Northern Territory – will count toward the national vote count but not toward the majority of states requirement.

Referendums don’t pass frequently. Only eight out of 44 previous referendums have passed in the country’s history.

The last time Australia voted on a referendum dealing with Indigenous affairs was in 1967.

This referendum made two things possible: the Commonwealth could count Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in the national census and make laws with respect to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

The referendum passed by a huge margin. With the government able to make laws about First Nations people for the first time, it ensured they would be protected by the Racial Discrimination Act that was passed in 1975. This act prohibits discrimination in employment, housing and access to public facilities, such as swimming pools, cinemas and shops.

But for all the 1967 referendum made possible, progress has been slow.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders make up a very small minority of the overall Australian population (less than 4%), so the right to vote has not always ensured political representation.

Although there are currently 11 Aboriginal members of parliament, they cannot represent all Aboriginal people. And there have yet to be any representatives at the Commonwealth level from the Torres Strait Islands (an archipelago between Australia and Papua New Guinea).

The ‘yes’ and ‘no’ campaigns

In the lead-up to this year’s referendum, the nation has been split along a stark “yes” and “no” divide.

The “yes” campaign has declared it’s time for change, emphasising how governments have consistently failed First Nations communities across the country.

They say better policy decisions result from local communities being heard on matters that affect them. To secure support from a mostly non-Indigenous population, the campaign also presents the Voice as an opportunity for all Australians to come together in support of recognition and democratic renewal.

Arguments against the Voice have been made on two different grounds.

Independent senator Lidia Thorpe, a DjabWurrung, Gunnai and Gunditjmara woman, has argued the Voice is a powerless advisory body. She has called for the government to pursue a treaty with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people instead.

However, treaty processes can take many years to progress. For example, the state of Victoria began a treaty process with First Nations people in 2018 and negotiations are only just about to commence.

The official “no” campaign, led by the conservative opposition parties, has depicted the proposed Voice as a body for elites in Canberra, the nation’s capital, which would be divisive for the country and prone to judicial overreach. “Yes” campaigners contend many of the “no” arguments are misinformation.

The significance of the vote

Even after 1967, it remains clear that existing voting rights and political institutions alone cannot represent the interests of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to the federal government.

Internationally, other countries have attempted to create improved political participation and government accountability for Indigenous peoples.

In New Zealand, for example, there is designated Māori representation in the parliament. In Scandinavia, the Sámi parliament represents seven Indigenous nations across Finland, Norway and Sweden. In Canada, First Nations people have both “first-contact” treaties that were negotiated upon European arrival, as well as modern treaties.

The 2023 referendum is the first occasion Australia has considered how Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people can be meaningfully represented in the federal government. Whatever the outcome of the referendum, it will send a powerful message to rest of the world about how Australians view their country.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.