A campaign for students and those on low incomes to get free travel on buses and trains is building steam.

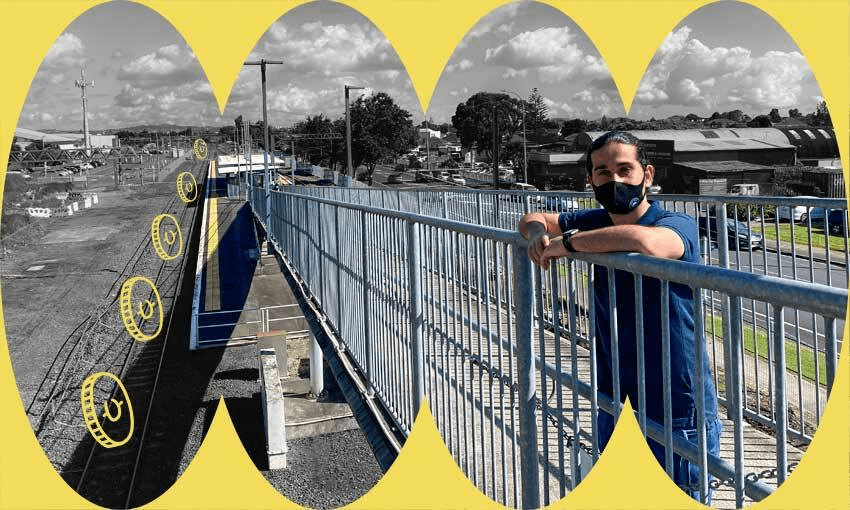

7am: Alan Shaker leaves his home in Manurewa and drives the short distance to the train station. If the car park is full, he drives a further 20 minutes north to the Papatoetoe station. Once he’s found a park, he jumps on the southern line, bound for Britomart.

8.40am: Ten stops later, Shaker disembarks in Auckland’s CBD.

9am: After a short walk up the steep hills around Auckland University, he’s arrived, just in time for his classes – he’s studying to become a secondary school science teacher. Later today, he’ll do the same trip in reverse.

The almost four-hour round trip costs Shaker $50 a week in train tickets plus whatever he needs that week for petrol. He says if he used buses instead it would make the trip even longer and more expensive.

It’s hardly walking barefoot in the snow for 10 miles, as some grizzled former students would tell you they did “back in our day”. But, Shaker says, the high price of public transport is a major reason more of his fellow South Auckland residents don’t go into higher learning.

With rent, utilities and food prices rising, he says the cost of public transport “is a huge factor, and so for many university just isn’t an option”.

The former Papatoetoe high school student says less than half of his peers have gone to university, and Auckland Council research backs him up, showing only 13% of South Auckland school leavers have completed a bachelor’s degree, compared with 43% in the rest of Auckland.

Shaker believes if public transport was made free for tertiary students, along with all community service card holders and those under 25, it would “level the playing field” for those in his region.

“It’s about making sure everyone has an equal opportunity to get educated. Someone shouldn’t have to make a choice between staying home because they can’t afford it or going to university.”

And Shaker isn’t the only one who believes scrapping public transport fares for young people and students could have a transformative effect. He’s part of the nationwide Free Fares campaign organised by The Aotearoa Collective for Public Transport Equity, an alliance of more than 40 groups including the Public Service Association, a number of city councils, multiple students’ associations and the youth wings of the Greens and Labour Party.

Someone who has already experienced the benefits of free public transport is Fa’anana Efeso Collins, who gets the trips as a perk of his role as an Auckland councillor. He says the free fares policy is both a “win for the climate and for people”.

“We’ll get people out of their old gas-guzzling cars and we’ll see whole families taking the bus, as we’ve seen when Auckland Transport has made it free on weekends,” he says. “The ultimate cost of not doing this is a degraded environment and then we are never going to achieve the emission reductions that we want.”

He says the policy shouldn’t be seen as just a “subsidy for the poor”, noting the government’s recently-introduced electric vehicle subsidy has a similar purpose while predominantly benefitting a wealthier demographic. Free fares would also be a major win for people who are isolated due to their inability to travel and give back some dignity to those living in poverty, he says.

“The thing I see most regularly on my bus trips are people getting on with nothing on their Hop [payment] card and then they go into a negotiation with the bus drivers. If it was free you’ll also take away those intense and embarrassing encounters with the drivers.”

Massey University of Wellington student president Tessa Guest is one of the leaders of the campaign. She says the group is optimistic the Ministry of Transport will be taking the proposal seriously, given its potential to improve education and wellbeing opportunities for those on low incomes.

“From my perspective as a student association president, it will change people’s lives, by ensuring students can be on campus more and have more time to be a student. And for community service card holders, it’s currently a choice between eating and travelling within their communities, so it could be life-changing, as it would ensure people can be connected and not isolated.”

The policy does come with a hefty price tag. According to Auckland Transport, figures based on revenue prior to Covid show that providing free fares to the proposed target groups would cost $75 million to $100 million each year. An AT spokesperson added there could also be additional costs of up to $200 million a year to accommodate the extra demand that the free fares would create.

Asked about the campaign, transport minister Michael Wood said the government recognises the importance of increasing public transport use. It’s trialling the Community Connect scheme in Auckland next year that “will cut public transport fares in half for community service card holders”, before potentially rolling it out across the country.

“We recognise that cost can be a barrier to getting New Zealanders on board public transport options,” he said, adding that free fares policy is another option still on the table. “We’ll be consulting further on public transport affordability as part of the Emissions Reduction Plan, and this important issue will be considered.”

The Free Fares campaign is hoping the government will take the leap and make public transport freely available to all young people, students and those struggling to make ends meet. For those groups, they say, free bus and train fares could be the ticket to more opportunities and, ultimately, a better life.