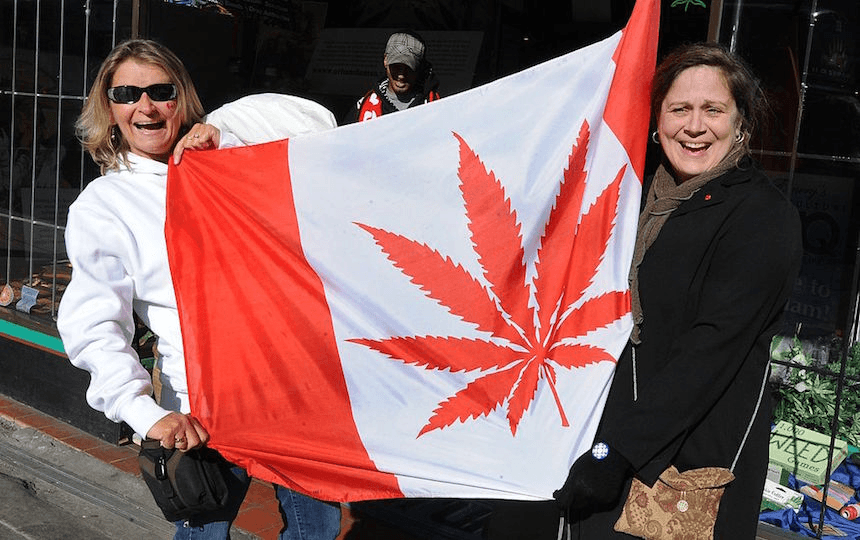

Former Canadian deputy prime minister Anne McLellan was in New Zealand last week to present at the NZ Drug Foundation symposium about her role in guiding Canada’s drug reform. She spoke to Simon Day about the road to legalisation, growing Canada’s ‘worst pot ever’, and the potential Baby Boomer weed market.

In July 2018 Canada will become the second country in the world to universally legalise cannabis (Uruguay took the plunge earlier this year). With one of the highest rates of youth cannabis use in the world, drug reform was a Justin Trudeau campaign promise in 2015. So after it was elected, the Liberal government appointed a panel to study how cannabis could legalised and regulated in Canada.

At the head of the Task Force on Cannabis Legalization and Regulation was Anne McLellan, a former minister in the Liberal governments from 1997 to 2006, and Deputy Prime Minister from 2003. During this time McLellan was no friend of reform. As she acknowledges, she was part of a generation that was raised to be opposed to cannabis, distrustful of an illicit drug and its reputation. Even as minister of health she was wary of the lack of scientific evidence around its benefits. Ten years later, cannabis activists were alarmed when McLellan was appointed as chair of the Task Force.

“When I was minister of health I was very sceptical. All of that created that impression on these activists that I was not going to be particularly open minded to legalisation and regulation of cannabis,” she says.

When the Tasks Force’s report landed late last year, with nearly 100 recommendations, the activists were pleasantly surprised.

“Ten or 11 years on I am probably a lot more open minded about what needs to happen around cannabis. It’s not only a journey for Canadian society, or the Canadian government, but it’s been a journey for me personally.”

Her journey has exposed her to the medical benefits of cannabis and the significant harms the current system’s management of the drug have caused. While the outcomes of Canada’s legalisation are are unknown and she recognises mistakes will be made, McLellan believes now is the time that Canada must try something different. The world is watching.

Why were you chosen to chair of the Task Force on Cannabis legalisation and regulation?

I think I ended up in this role because I was in federal politics at home in Canada. I was part of two governments, Prime Minister Chrétien’s and Prime Minister Martin’s. And at various times I was Minister of Justice and Attorney General, and Minister of Health, and Minister of Safety, and Deputy Prime Minister under Mr Martin. And right now, those three ministries – Health, Justice and Public Safety – are responsible for the implementation of a new regulatory regime around cannabis.

In some respects I was the least likely. My previous involvement with cannabis portfolios, was more on the – let me say – on the prohibitory side of this (laughs) than the legalisation or regulation side.

But I think I’ve been out of politics now 10, 11 years – since January 06 – so a lot changes in life, in a decade. You learn a lot, one hopes you get smarter. You have time to reflect on some of the things you did while you were in government that didn’t work out the way you would have hoped.

In your previous life as an MP, you would have been opposed to legalisation of cannabis?

At the beginning when I was dealing with this as Minister of Health, we were very sceptical. We knew very little about the medical benefits of cannabis. What we had was experiential evidence, people who were saying – it helps me with a pain, it helps get me through my chemotherapy, the nausea, the lack of appetite. But as departments of health we’re used to clinical trials, we’re used to science based evidence. So you end up being sceptical of these experiential claims.

I probably wasn’t thinking about legalisation back then. Nobody was talking about – I shouldn’t say nobody, cannabis activists [have been calling for legalisation] not only been in our country but in other countries for a long time.

As Minister of Health my predecessor in the health portfolio began the process of medical marijuana. It was actually the courts, and people going to court, and saying; “Hey, you know what? I need this. This is the only thing that helps me with this condition or that.” And so when I became Minister of Health, it was at the very beginning of our medicinal marijuana regime.

We used to laugh about the fact that I had the only legal grow-op in the country as Minister of Health. We as the government decided that we would provide the product to those who had medical authorisation. So my predecessor made the decision that we would grow our cannabis in a deserted mine, outside Flin Flon, Manitoba, hundreds of metres underground.

We would laugh about the fact that anybody who used that product from that mine said: “Minister, you have the worst pot in this country. It is terrible.” I think they were probably right about that. I never used any of it myself but I can imagine probably how unimpressive the product was coming out of that mine.

How has your understanding of people’s experience of using cannabis changed?

One of the things that we talk about in the Task Force report is the fact that it is important to take in experiential evidence. For example, a mother was telling us her experience with her 5-year-old who has the most severe form of epilepsy and conventional-based interventions were not dealing with the number of seizures, sometimes up to a 100 a day. And turning her child into virtually a zombie from all the medication.

In desperation, so many parents who have children with this severe form of epilepsy turn to CBD (Cannabidiol)-high cannabis products. And her experience – there’s very little clinical evidence to explain this… after she and her husband went into the illegal market place – so they are breaking the law – to find this product for their five year old, that child can now go up to two weeks without a seizure. There’s no clinical trial that explains that yet. But you have to take on board that experience. You have to say – there’s something going on here, and we can’t ignore it.

It’s easy to think that people are making these claims because they just want to get high. That’s kind of how you’re brought up. And even doctors in Canada, and here [in NZ] too I saw one quoted in the paper, they’re very sceptical. Because this is not the kind of evidence they’re used to. And we still haven’t done all the clinical work that we need to. But it seems to me that at this point in my life, when I hear those kinds of experiences, from people like that mother and so many other patients that we heard from, there’s something that we have to take on board here. And we have to embrace the potential medicinal benefits of cannabis.

With legalisation it seems to be a war of narrative in many ways. It’s really interesting that you’ve managed to maneuver past your scepticism over those 10 years through hearing those stories of the people who have been affected.

There’s a lot of activists in Canada who were absolutely shocked. One, they were not happy when I was appointed chair because of some of this history. But two, I think they were even more surprised when the Task Force report came out and some of our major activists like Mark Emery were saying – “You know what? I thought I’d never say this, but I think I agree with Anne McLellan.”

Now we don’t agree with all the claims the activists make, but certainly in terms of trying to figure out a better way forward for our society we would agree that ongoing criminalisation, criminal records for young people, a lack of openness to research and science based knowledge [isn’t working].

Why legalisation now? What was happening in Canada that meant the government felt this was possible?

One of the things that changed was the fact that Justin Trudeau was leader of the Liberal party. And he made the promise in the lead up to the 2015 election, that if elected they would legalise, strictly regulate and restrict access to cannabis. He wants to deal with the fact a great many young people were ending up in the criminal justice system for personal possession charges. And the impact of that on the court system, tens of thousands of charges a year for personal possession which would be on a young person’s record, which means that they may have trouble getting employment, or have a lot of trouble getting into the United States, or potentially other countries.

The illegal criminal organisations are making a lot of money, billions of dollars a year, by selling illegal products. Some of it, undoubtedly cut with other substances that are much more dangerous than the cannabis itself. No quality control in relation to what’s being sold on the streets.

For Mr Trudeau and the Liberal Party, they said – “you know what, we have the highest youth rates in the world of cannabis use. And prohibition hasn’t stopped that. So let’s try something else.” Let’s think about what other public policy responses, other than criminal prohibition might help us in terms of dealing with those high rates, helping young people understand the risks. Opening the door to a lot more research, more public education around cannabis.

You have the experience of states like Colorado and Washington in the United States. So even though the U.S continued prohibition at the national level, states were legalising, you could look at that experience. We as a Task Force visited both Colorado and Washington, we talked to people in Oregon, we talked to the people in Uruguay – which is the only country that’s legalised at the national level.

I think if you put all of that together, it probably just seemed to be the right time to say: we have to be able to do better. We’re not doing a very good job of stopping young people using. We’re forcing them into a black market, which could be more dangerous for them than legalising and regulating.

When you frame the argument as legalisation in order to protect children, restrict the money making capacity of gangs, and to allow better research into the effects of cannabis, how has the Canadian public responded?

As we went through our work as a Task Force, and it was over five to six month period anywhere between 60-70% of Canadians, depending on the province, would say “yes, I’m in favour of either decriminalisation or legalisation”. About two thirds of the Canadian population were ready for a change from the policy we had. That they figured that the ongoing criminal prohibition regime was not the way to go.

The closer it comes to the reality of legalisation, you see the support numbers go down. Because people are starting to come to grips with what this means for them and their community. They’re starting to think about – do I want a retail outlet selling cannabis on my street? Are we going to see a spike in usage that is going to lead to more pressure on our mental health issues, our addiction services?

But the problems exist now. And we haven’t dealt with them very effectively, so let’s try something else and do better.

In New Zealand, the police has basically been given implicit permission to decriminalise cannabis because the government won’t change the law.

Well at home, the challenge is confusion about existing law, and the ability of enforcement. Because in a lot of major urban centres in Canada, the police have bigger things to deal with if they find somebody with a small amount of cannabis, they may confiscate it, but a lot of times they’re not going to bother charging. It’s a waste of their time.

Whereas in some smaller communities and in rural Canada, the police take a quite different approach to that and they may charge. And people end up going to court. One, it creates confusion around the law. But two, it also calls the law into disrepute, because there’s no clarity around how the law’s enforced.

And we have the same issues that other jurisdictions have, in terms of concerns around of indigenous people who end up being charged more frequently, and African Canadians who end up being charged more frequently. So all of this speaks to the fact that criminal law around personal possession of cannabis is a confused situation right now. And whether you get charged for simple possession may depend on where you live. Or even what part of the city you may live in, or what you look like. And that’s not a good thing for the criminal law, and its not a good thing for law enforcement to be put in that position either.

Are drug laws amplifying the social problems that indigenous communities already faced?

Absolutely. Or some of our African Canadians in major urban centres. The whole discussion of disparate race-based effects, or applications of the criminal law are topics that are uncomfortable for many people to discuss but are realities out there that people need to be honest about and address.

So what will legalisation look like in Canada?

Basically personal possession of a reasonable amount is no longer against the law. Anyone over the age of 18, can have on their person in public up to 30 grams. They can buy up to 30 grams in one sale. We are also authorising that in any one home you can grow up to four plants for personal use.

But we are also establishing a highly regulated legal market place. We are taking a product that has heretofore been prohibited, and we are creating a legal market around that product. The last time that happened was alcohol in the 1930s, after prohibition. That was the last time we’ve seen a product go from prohibition to a legal market and everything that goes with a regulated legal market.

If you go back and look at the transition period between prohibition and the establishment of legal markets for alcohol, there are lessons that can be learned. One of which is that it takes time.

As of July 2018, we’re not going to magically have the perfect legal market, we just won’t. Because it will take time to see that retail market develop. It will take time to work out the fluctuations of supply and demand. It will take time to figure out the licence producers. And what the price point should be to try and cut out the black market. And people shouldn’t be surprised by that. And I’d even go so far to say probably it will be a little messy initially.

But one of our cautions to government in the Task Force report is that governments should not overreact on underreact to that. That government need to be nimble and flexible and understand that this market will not be perfect on day one, and it will take some time to develop the market in legal cannabis. There will be some mistakes made, and we’ll have to correct the mistakes.

Are you going to be growing cannabis again in 2018?

The government’s not in the business of growing cannabis anymore. Remember where we started. So this is going to be private sector growers and they see the opportunity to have a very profitable business. All of a sudden, you’ve got this whole new product that wasn’t legal before and now there’s a demand for it. Quite honestly, there is money to be made on the part of those who are growing the product. And I think you see that reflected in the interest of people getting into this sector, the growth of this sector, companies being traded on the Canadian stock exchange. We have our first billion dollar cannabis company – Canopy.

Even though we as a Task Force and the government of Canada, we’re not promoting use, we’re not promoting commercialisation; our goals are public health and public safety. Once you create the market, there will be, just as with any market place, laws of supply and demand that will dictate who succeeds and who doesn’t.

In our report we talk about the importance of artisanal and craft growers. We have literally thousands of illegal growers in Canada who have been growing for years and selling perhaps in local farmers markets, and law enforcement kind of turned a blind eye to that. It’s not organised crime, it’s not the Hell’s Angels. It’s someone who’s growing their 300 – 500 plants and taking their product to the local market in the interior of British Columbia, or they sell to their regular customers. There’s this whole boutique industry out there, all of which is illegal.

A lot of these growers have a lot of expertise. And here I’m not speaking for the government of Canada, but I’ve come to the conclusion that you want to get as many of these people into the legal market as possible. Just because you may have had a criminal conviction for simple possession in the past as a grower, in my opinion that should not automatically exclude you from being able to apply to be part of the legal market. And we probably need those people and their expertise.

I don’t imagine it will be the same as buying a block of cheese though? In New Zealand, for example, we have a highly regulated environment for the sale of tobacco.

And that’s exactly the same back home. In our Task Force report in fact, we recommend you take an approach that’s very similar to tobacco in terms of packaging, marketing, advertising and promotion. So we recommend no sponsorships, no celebrity endorsements, no billboards, no lifestyle advertising such as you see with alcohol, and you used to see with tobacco. It’s very close to a plain packaging regime that we are recommending.

In a retail establishment, where only people over the age of 18 are allowed, companies should be allowed to promote their product to a certain degree. They should be able to establish their brand to a certain degree. But in terms of the product itself, pretty much plain packaging, but it will have name of the company, the logo, the approx amount of THC or CBD. It will have a warning label on it.

We’ve talked a lot about the benefits of the market and how it will work. How do you then make sure that the government’s health and protection outcomes are happening – how do those taxes then go back in into ensuring the least possible harm is coming of this new approach to cannabis?

There are no absolute guarantees but the Prime Minister has been very clear that revenues collected by the Federal Government should go into mental health programming, addictions programming, research, supportive clinical trials. And when we met with the provinces and territories, they all took the same approach.

A fair bit of upfront money is going to have to be spent before any revenue comes in the door in terms of public education programmes, that is one of the things that we talk a lot about in the Task Force report. If we are going to meet your public health and public safety objectives, you have to have good public health initiatives.

We learnt a lot from tobacco. When I was Minister of Health, I remember all the sessions we had and the focus groups around tobacco public education and what would reach young people and what wouldn’t. And there were a lot of mistakes made. I would like to think we are a lot better at understanding what public education reaches young people. And that takes money. It takes time. So revenues should be used for those purposes initially.

If you just take those revenues and divert them to government expenditures, there will be a price to pay down the road. As we have learned with alcohol and tobacco.

By removing some of the stigma, are you making services more easily available, are you using the legalisation of cannabis as a way of dealing with those problems, rather than criminalising those problems?

We are acknowledging the problems and trying to find better ways to deal with them. Maybe in a way it’s been a bit of a head in the sand in that we knew these problems were there, we’ve known that we weren’t effectively dealing with them, so now maybe it’s time in this bold new world to say – let’s try something else.

If these things are no longer criminalised, people will be willing to talk about them, more willing to acknowledge a problem, that they’re a user, and they need help. They can step out of the shadows and we can deal with all these issues in a more intelligent, holistic way than we’ve been able to. The criminal law is a blunt instrument, It doesn’t help people who have an addiction.

Are you concerned about the public response if things don’t go to plan?

One of my fears is that people will be quick to blame if there’s an accident in a workplace, that that’s because of cannabis legalisation. Or if there’s a terrible accident on the highway, that’s because of cannabis legalisation. Let’s blame this new public policy initiative for bad things that happen and that’s when governments get scared. Because that’s when politicians start to hear from their voters.

Part of what we wanted to do in the Task Force is make the point very clearly that there will be surprises, and we will make mistakes. This is a very complex public policy change. With cascading effects, from the government of Canada, to the provinces, to the street level and municipalities and communities all over Canada. And that we have to prepared for that, we have to be flexible and nimble.

How much has your opinion changed when a hypothetical example like your children using marijuana recreationally ten years ago, to that same use once it’s legal?

Well…. It would be my grandchildren!

But your children, or even yourself, will be in a position where you will be able to on a Saturday evening with friends have a glass of wine and a joint?

That is part of the transformation, the change that people have to wrap their minds around. And it will take time to move from being brought up in a regime where this was a prohibited substance to one where you can stop on the way home just like I pick up a bottle of wine and I think nothing of it. And now you can go to retailer selling cannabis, and pick up X number of grams, and have people over. And have people over, for a glass of wine, or for cannabis, in whatever form. Not that we would suggest smoking is a good idea. Smoking anything is not a good idea.)

I think you want to talk to your kids the way you would about alcohol, the way you would about tobacco, and say, there are risks, and it’s legal for mum and dad to have a drink, and it’s legal for mum and dad to use cannabis. It’s all part and parcel of bringing your kids up and helping them understand that you shouldn’t use until you’re a certain age and you should make intelligent decisions. And always feel free to talk to me as your mum or dad or grandmother or whatever. So it seems to me we have to get used to talking to our kids and grandkids about cannabis use.

What about you and your friends?

In terms of my generation, I’m a Boomer, as we age I think you’re going to see a growth in use. We’re used to having things our own way, we’re used to making our own decisions, having a choice. Thinking this through for myself, if one could use cannabis in whatever form to deal with chronic pain, or as we age more likely to get cancer, dealing with the aftermath of chemo or radiation, we will say that we want access to whatever it is that might help us live a quality life, and if that’s cannabis, we’ll use cannabis.

So I actually think you’ll see seniors be part of the growth industry. Because they will see it as a medicinal treatment, but they might also see it as something pleasurable. Something to do like a glass of wine. So it’s interesting, I hope I live long enough to see, 20 years, 30 years from now where is the growth.

I would like to see underage youth drop. But my guess is, at the higher end, at the senior end, you’re going to see a substantial growth in cannabis use.

A fresh way to deal with drugs is needed more than ever in New Zealand. The Drug Foundation’s roadmap for reform Whakawātea te Huarahi – A model drug law to 2020 and beyond is available online.