The activity to which Max Olijnyk has devoted much of his life has been given the ultimate mainstream seal of approval, and it cuts both ways.

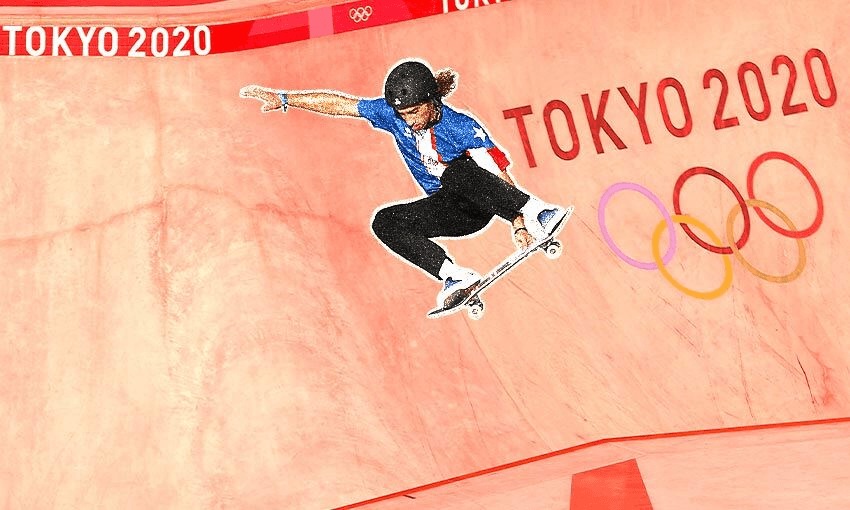

Last Monday, I sat in Wellington Regional Hospital with our new baby on my lap and watched the first ever women’s street skateboarding event at the Olympics. (I missed the men’s division on Sunday because my wife was in labour). As a long-time skateboarder, this was quite a profound moment – even if the version of skateboarding the Olympics served us was very different to the all-encompassing lifestyle that captured my 12-year-old imagination all those years ago.

I’m not sure what inspired me to pick up my first skateboarding magazine in 1988, but through ingesting its contents, my life was irrevocably changed. That magazine, along with the countless others that followed it and the VHS tapes that brought the imagery to life, were an inside line to a culture that was more vital and unfiltered than anything I’d ever experienced. And by rolling around at the local primary school, I could plug myself into that culture from afar.

To me, skateboarders were the coolest people in the world. Skateboarding informed and influenced every stage of my life. Everything I was looking for could be found within its pages, its words, its movements. And part of its allure was its exclusivity – you only saw the magic if you were already part of it. To the rest of the world, skateboarding seemed to be really annoying.

I have been yelled at from passing cars and ejected from public spaces all over the world. I have been punched in the face and bitten by dogs, all because I am a skateboarder. All that served to make me aware of the huge disparity in how people can be treated in our society, as well as instilling a lifelong distrust of authority.

So it cuts both ways to see skateboarding afforded the ultimate mainstream seal of approval by becoming an Olympic sport. On the one hand, the activity I have devoted much of my life to is being showcased as something that is deserving of everyone’s attention. By virtue of its inclusion, “Olympic-grade” skateparks are being built and council’s attitudes towards skateboarders are shifting from hostile “No Skateboarding” signs and “skate stopper” architecture to a more collaborative approach that incorporates skateboarding into public spaces. Perhaps we are moving into an era in which skateboarding is a more universally celebrated part of culture, and no longer an outsider activity.

I worry, though, that the exposure afforded to skateboarding through the Olympics will do little good for skateboarding, because it presents it merely as a sideshow and spectacle. The announcers of the street competition were a couple of goons who routinely misnamed tricks and joked about how they hadn’t stepped on a board since their college days. The skaters are amazing, of course; but they represent the jock-ish end of the spectrum. Much of the magic and eccentricity that first attracted me to skateboarding has been rinsed out of this package, and I wonder if any of that magic will still make it through the screens to anyone looking for something to connect to and base their lives around.

I’ll definitely be tuning in to the park skateboarding today from the comfort of my living room, with a nearly two-week-old baby on my knee. He seems to enjoy it, though I realise for him it’s just a mass of moving blobs of colour.

Olympic park skateboarding: What to look out for

Park skateboarding is based around a course of curved walls and bowls – a skatepark, as opposed to the stairs, rails and wedged ramps of the street course, which is a rough approximation of an urban environment. Each skater receives three 45-second runs that they are graded on (this is highly subjective, but don’t get me started), and the highest individual score wins.

Women’s park (Wednesday, August 5)

Lizzie Armanto (Finland): Lizzie was the first female skater to successfully do “the loop” – basically a Hot Wheels-style track that shoots you around upside down and spits you out the other side. She also falls over a lot.

Sky Brown (Great Britain): Everyone in the media is excited about Sky Brown. She is 13 years old and her name is Sky, I get it.

Brighton Zeuner (United States): I like Brighton, she skates with a classic style. She is sponsored by Frog Skateboards, which is a super cool board company.

Men’s park (Thursday, August 6)

Andy Anderson (Canada): This guy is an interesting one. His background is in freestyle, an archaic yet innovative subset of skateboarding involving handstands and jumping up and down on the spot.

Pedro Barros (Brazil): A very powerful skateboarder. Not exactly known for his subtle grace, if you know what I’m saying.

Oskar Rozenberg (Sweden): This is the magic I was talking about earlier. Oski is a graduate of Bryggeriet, the world’s first skateboarding high school. He is incredibly skilled and fluid.