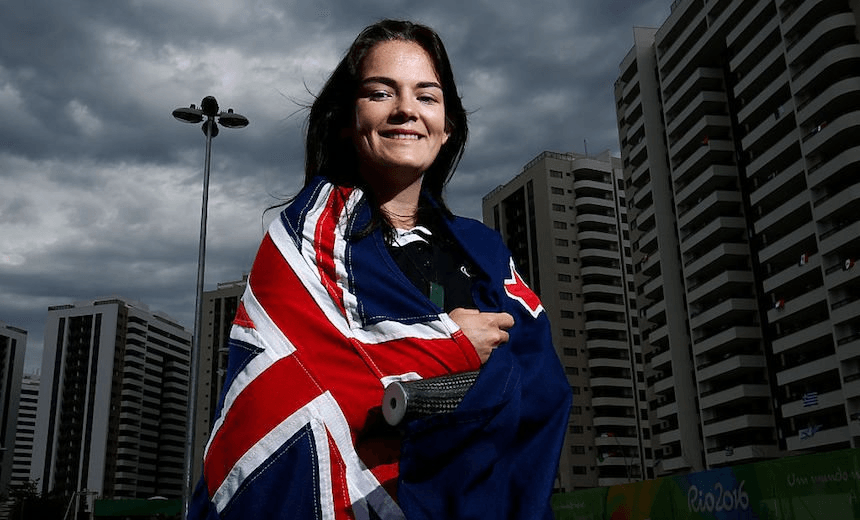

The opening ceremony for the Rio 2016 Paralympic Games is today. Kirsten McKenzie was there for the Olympic Games and argues that Rio was not only safer than expected, it was far more inclusive than most major cities.

The countdown is on for the 2016 Rio Paralympics. There’s little fanfare in the traditional media. There’s no buzz in workplace corridors, or long essays in the NZ Herald about the expected medal tally for New Zealand. It’s a very different beast to that of the all consuming summer Olympics I have just returned from.

On the flight to Rio, I imbibed the Olympic spirit by binge watching the three olympic offerings in the entertainment section: The Race, a biopic about the sprinter Jessie Owens grappling for racial equality in both America and Germany. Chariots of Fire, another biopic, featuring the struggle for religious equality and inclusiveness. And finally, Eddie the Eagle, which you could argue is about the fight for inclusion, or the fight against the exclusion of those considered less than whole.

Each movie a piece of Olympic propaganda, designed to tug at the heartstrings, to strengthen the notion that to strive for the Olympics is a noble endeavour. It certainly left me contemplating which Olympic level sports were suitable for a woman my age to take up upon my return to New Zealand (hint: not many). Sadly it seems that our Paralympic athletes are facing similar struggles of acceptance, and for their share of airplay, despite their world dominance in many of their chosen sports.

Traveling to Rio on an Air New Zealand plane filled to the gunnels with black t-shirts, you could have been forgiven for thinking that we were on a Black Sabbath charter flight, instead of the direct flight from Auckland to South America. What a proud nation we must be when we can fill an entire plane with family, friends and supporters of our athletes. With that level of support for all our athletes, both able-bodied and not, it still astounds that only mainstream sports get any sort of coverage outside of the Olympics.

Imagine the athletes, and the inclusive society, we could grow if those other sports had a mere fraction of the coverage rugby and league enjoy in our papers and on our television sets.

I know we had an expensive flag referendum, where people (other than almost everyone I know), voted for the status quo, but seriously, the world must think that our flag is the iconic silver fern on a black background. It was everywhere. Gracing drink bottles and flags, t-shirts and backpacks, jandals and hats. The only time we saw New Zealand’s official flag was during the medal ceremonies.

As travellers, we’d been given an expectation that Rio was a battleground, populated with gun-toting warlords and battalions of homeless filling the third-world streets. After registering with Safe Travel, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs service to track New Zealanders overseas, the emails we started to receive from them were nothing short of terrifying. I’m surprised we ever left New Zealand, and that we sent any athletes at all.

The Rio we saw was anything but the hybrid of war-torn Syria and Pablo Escobar’s centre of operations we’d been told to expect. Rio had an air of 2011 Auckland about it. Remember that time when we’d just been delivered a gleaming Wynyard Quarter and those wide avenues spanning Eden Park? When bars and restaurants sprouted faster than potential mayoral candidates promising rates rebates and urban growth. And as Aucklander’s, we were given wonderful open spaces, family spaces to treasure long after the golden glow of the Rugby World Cup had passed.

From the version of Rio we saw, they will be left with some amazing open public spaces, which felt as safe as houses – you know, the well insulated four-bedroom sort, surrounded by old trees and nicely mown grass verges? Admittedly, there were enough uniformed men around to mount their own well-armed war against ISIS, but the overall vibe of the city was a welcoming one, a happy one, full of your stock standard family groups, young couples, girls travelling in packs, and old men ambling along oblivious to the crowds. And a Rio which has a high functioning public transport system.

For the 2016 Olympics, the public transport system in Rio was given an overhaul. There was much in the media about how it doesn’t go as far as it should, or through to the right places. But then again, what public transport system, anywhere in the world, is perfect? At least Rio has one. One which was easy to access, easy to navigate, and delivered tens of thousands of tourists to destinations as far away from each other as they could possibly be. A public transport system, and a population, ready and adult enough, to recognise the needs of others.

Travelling with my mother, who is old enough to receive the pension, but not old enough for me to be allowed to tell you her actual age, was an experience in what New Zealand does not have: respect for its elderly; its expectant mothers; its physically disabled citizens.

During two weeks of travelling on a well utilised public transport system, which at times appeared to be at or beyond capacity, where I was relegated to standing on most trips, only twice was my elderly mother left standing. On every trip, bar two, someone offered her a seat on the crowded train, bus, tube. Students, young men, old men, young women. It didn’t matter who they were, they all, without hesitation offered their seat to her. We watched it happen again and again, at different stops, to different people. The elderly, people on crutches, women holding babies. People willingly stood up and offered their seats to them, to strangers who needed a seat more than they did. What a miracle of manners. And it wasn’t confined to public transport.

All the Olympic venues had a priority queue designated for the elderly, for the disabled, for pregnant women, and for those with very small children (families with teenagers were firmly moved on from these queues). It is a sign of an enlightened society when those who are our most vulnerable are appreciated and considered. And my mother loved it.

Say all you want about the dangers of Rio, about the gun violence, and the terrors of turf wars, the only time I ever had a gun pointed at me, was in Auckland. The only time my bag was snatched, was in London. They must be doing something right in Rio to have the level of courtesy we saw displayed on a daily basis throughout the city. You can’t magic up courtesy like that just for a sporting event, no matter how many volunteers you draft in to help. It just isn’t possible.

It is that level of courtesy which will make the Paralympics as successful as the Summer Olympics. When you have a population already accustomed to accommodating those who might need more assistance than others, you create acceptance. You have a society who are raising children with the personal maturity to accept someone who looks different, or who sounds different, without judgment.

It is with this in mind I’m hopeful our athletes find Rio de Janeiro as accommodating as we did. That they succeed on the international stage, at venues we, as spectators, found to be well designed for all physical abilities. And maybe, just maybe, the media might give our Paralympic athletes the same level of coverage as last months able bodied athletes. Because if Rio can do it, we can do it too.