Despite being diagnosed with cancer, I was doing really well – until I stopped sleeping.

The Sunday Essay is made possible thanks to the support of Creative New Zealand.

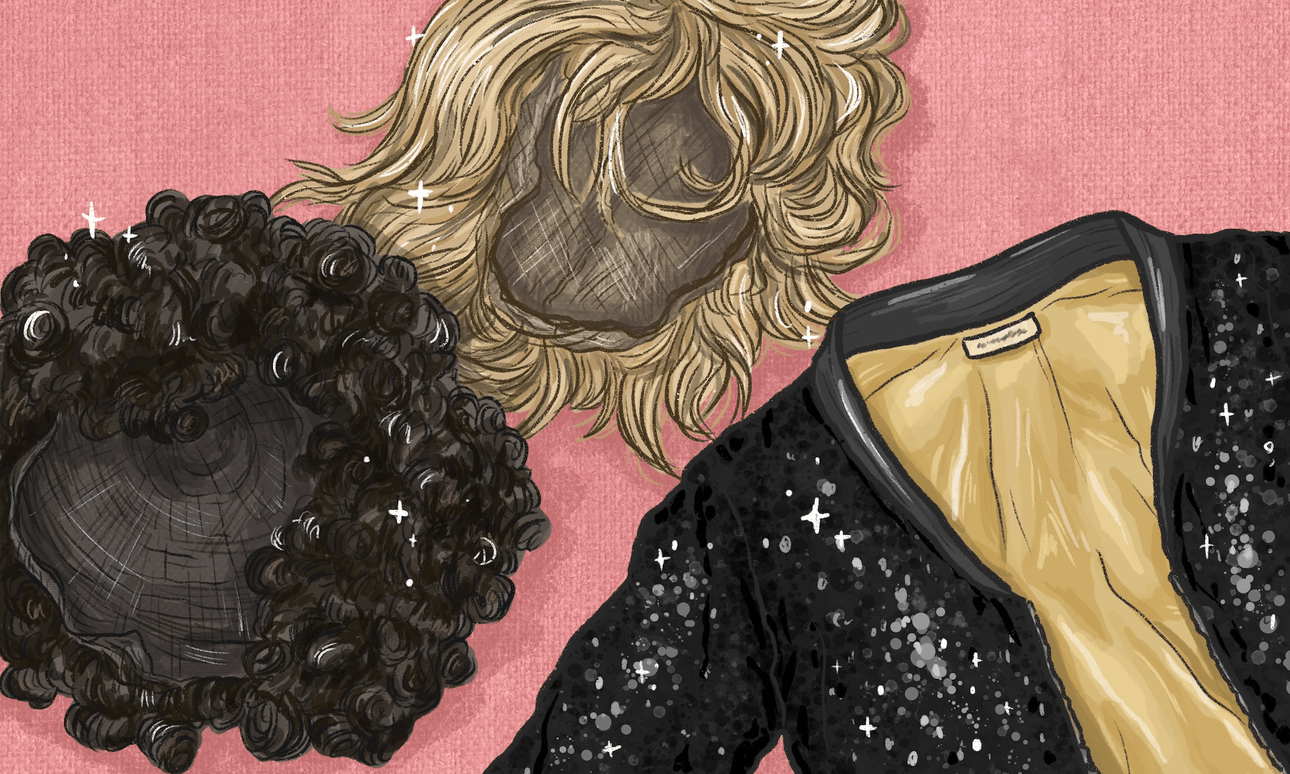

Illustrations by Jewelia Howard..

In June I stopped sleeping and went a bit mad. For about six weeks I was averaging around two hours sleep a night. There were some nights where I didn’t sleep at all. Everything went sideways, real fast. I started stuttering. My body was jumpy and my eyes twitchy. I lost my appetite. I moved through the world like I was underwater and far away.

Funny things happen when you’re that sleep deprived. I had conversations with people that I simply don’t remember. I put a pencil in the fridge. Allegedly I went to Top Gun. The days and nights collapsed into each other. Perhaps most alarming of all was the online shopping. At some point during the haze, a parcel arrived with my name on it. When I opened it up I was assaulted by a spangle of sequins. Evidently, I had bought a black sequin dress and matching black sequin jacket, like some kind of unrealised (unconscious?) homage to Liza Minnelli. I have no recollection of ordering this, nor do I have any occasion to wear sequins.

I discovered that when you don’t sleep you wind up crying a lot. Loud noises and bright lights are too much. Anxiety sets in. My nerves felt quite literally frayed like exposed wires, my heart would pound so hard that it made my t-shirt tremble. My stomach churned and gurgled.

I tried all the sleeping pills; Zopiclone, Amitriptyline, Nortriptyline, Temazepam, Quetiapine (this one is an anti-psychotic but in low doses is supposed to help you sleep). One of them worked, the rest didn’t. I took magnesium, melatonin, sour cherry juice, sleep tea, CBD, CBD with THC (I spent one night accidentally and terrifically wasted imagining that the bed was swallowing me up every time I closed my eyes). I read everything I could get my hands on about sleep. I tried Epsom salts in the bath. I ate more protein at night, microwaving a cup of milk at 3am, trying to drink it but then retching. I hate milk. I ate dinner early, I avoided exercise at the end of the day, I limited screen time in the evening. I tried tapping, mindfulness, guided meditation and sleep stories. I can recommend ‘The Glassmaker of Murano’ if you like to be bored to death over and over again. It’s astonishing how dull someone can be. One of my darkest moments was the first time I reached the end of the sleep story. You’re not supposed to reach the end of those stories. At one point I googled: “Can you die from lack of sleep?”

It’s difficult to determine the precise reason I stopped sleeping, because it was undoubtedly a combination of factors. Cancer being the main one. Last year, I was diagnosed with aggressive breast cancer, just before Auckland’s interminable level four delta lockdown. I was fortunate in that it was discovered early – and lucky it was discovered at all, given it eluded detection in two mammograms and an ultrasound. I had surgery, three months of chemo, 19 rounds of radiation and I’m now on hormone therapy for the next five years.

There were silver linings to having cancer in lockdown. When the chemo wiped out my white blood cells compromising my immunity, I didn’t have to worry about catching bugs off others since we were all isolating. My kids weren’t bringing home colds from school, because they were already at home ALL THE TIME. I wasn’t missing out on any fun events either, because there were none happening. Very few people saw me really sick and bald, which meant I didn’t have to deal with well-meaning, awkward interactions.

And while we’re on this topic, here’s some things not to say to someone with cancer:

“What’s your prognosis?”

“Are you asking if and when I might die?”

“Yes”

“Yeah, maybe just don’t.”

“I knew someone who had cancer.”

“How are they now?”

“Er. Dead.”

These are things that are acceptable to say if you are an eight-year-old:

“Your head looks like it’s covered in nostril hair and it makes me feel weird. Can you grow it back?”

“Please don’t die.”

Anyhow, it’s true what they say about how when something bad like this happens, you get to see the goodness in people. It’s in the outpouring of generosity and love from family and friends. And it’s in the kindness of strangers; the basket of woollen beanies in the oncology ward knitted by one of the doctors in her spare time. It’s in the hospital orderly’s quiet singing at 3am as he wheeled me in for scans, taking an extra blanket and tucking it all the way up to my chin so I wouldn’t be cold. It’s in the young barber who gently shaved off what little hair I had left and then refused to charge me.

There’s a lot of humour in cancer if you want to look for it. Take wigs for example.

I ordered a wig at the beginning of my chemo treatment and was told it would take around a week. Three months later it arrived from Germany, a week after my final chemo session. In the meantime, I looked on Trade Me for wigs. There were all manner of wigs on there, but the standout was the one that looked like a black frazzled dead thing. It was an eletrocuted ebony cat. It was a large, dark tumbleweed. It was a dust ball the size of a bicycle helmet. It was five dollars and so spectacularly bad that it brought me great joy.

My husband wanted to help me find a wig so contacted a friend who is a drag queen. Yes, there was a wig I could borrow. He collected it and brought it home but hadn’t thought to ask about the colour, which resembled dirty dish water. Or, more formally (and generously) described as “ash blonde”. I put it on my head and my sister couldn’t talk for laughing. Bent over, wheezing in hysterics. Because the universe is a marvellous place, I happened to be wearing overalls that day. The resemblance to Worzel Gummidge was uncanny.

The thing about receiving bad health news at a reasonably young age – I’m 42 – is that you begin thinking about how you might be remembered when you die. The stories you leave behind, the tales people will tell, the good, the bad, the weird. Will they talk about the pets you once had? Bessie Bunter the pig, Aristotle the axolotl, Cecil the peacock who landed on the roof of your suburban Hamilton home one day and never left. Will they talk about how you could read by age three, but only got 51% in School C maths after six months of tutoring? Will they mention the time you decided in your infinite 11-year-old wisdom that what your intermediate school really needed was to experience your choreographed dance routine to Sir Mix-A-Lot’s ‘Baby Got Back’ during the school assembly? Will they talk about how you travelled the world, lived in different places, got married, had a couple of lovely kids and lived a good, ordinary life? Will they talk about the astonishing number of pot plants you have drowned because you loved them too much? Will they talk about that essay you once wrote about when you couldn’t sleep and you had the audacity and bombastic self-importance to ponder your legacy?

On the darker days you make deals with ghosts, pleading to have enough years to see your kids through to adulthood. Anything after that is a bonus. In the darkest moments you beg to get them through childhood. But you have nothing to offer in return.

Up until I stopped sleeping I was doing really well. “I’m doing really well,” I said to anyone who asked. I had done everything the doctors had recommended and more. I was attending pilates twice a week and avoiding bacon. My hair grew back, albeit as a riot of curls reminiscent of Napoleon Dynamite (chemo curls – it’s a thing). My immunity returned; now I could catch Covid – and I did – and enjoy it just as much as a healthy person. I gained back some of the weight I had lost. I know this because a massage therapist patted me on my bottom as I lay in front of her on the bed and said approvingly: “Fatter, good.” Which I relished, because the last time I saw her she told me I was too skinny while she poked at my hipbones and told me to eat more ice-cream.

Then the sleeping went haywire and the wheels fell off. I later learned that this is not uncommon around six months after treatment ends. Kill phase. That’s what they call the active part of cancer treatment when your body is being infused with toxic drugs designed to destroy cancer cells – and every other cell in the process. That’s followed by daily radiation sessions that leave your skin blistered and peeling. There’s a calm that descends during this time knowing that you are, in that moment, doing everything possible to ensure that any rogue cells are being destroyed and zapped. It’s a surrender to the process. But once the kill phase is over, the realisation dawns that cancer cells could be once again flourishing, in the way they did the first time around. Recurrence is a constant threat. You no longer trust your body the way you used to. Aches and pains and twinges could mean it’s back.

Last month, in an attempt to win back my sleep and sanity I left my family at home and went to Alaska. On a cruise ship called Quantum of the Seas, a gargantuan floating mall, with 15 floors, a surf simulator, bumper cars, a skydiving tunnel, and 6,000 other morons cruising up the coast of the American continent. It represented everything that’s wrong with capitalism and the west’s culture of excess and consumption. And by god, it was magnificent. I played bingo and trivia, joined a silent disco, attended an Elton John impersonator show and watched the absolute shitshow that is cruise ship karaoke. I drank pina coladas and missed the towel-folding seminar because I was at ‘The World’s Sexiest Man Competition’. The absolute cheek of it. As if the world’s sexiest man would be riding the Quantum of the Seas to Alaska. The gentleman who won enjoyed wearing loafers with no socks and executed an astonishing impression of a dolphin, squeaking and jerking around on the floor. I played ping pong, strode around the running track on the 15th floor in Birkenstocks with socks, photographed the cheese sculptures and considered striking up a conversation with a chubby, old white fella in Osh Kosh denim dungarees and a Make America Great Again cap. I had the goddamn time of my life.

Someone asked me the other day if I see life differently now, have I experienced some kind of profound shift in perspective because of cancer? Do I feel #blessed? The answer is no. There has been no come to Jesus moment. Sometimes life is just a dick.

Things are good now. Actually, they’re great. I’m back home, I’m sleeping again. I returned the sequins and got my money back.