A fringe economist, a narrow frame of evidence, and planners who made up their own minds on the law of supply and demand. The story of how Wellington’s independent hearing panel turned against new housing.

The independent hearings panel for Wellington’s new District Plan has stripped back new housing capacity, expanded character areas, decided the Johnsonville train isn’t a train, and made perplexing rulings about whether it’s possible to walk up a hill.

The panel’s recommendations have been criticised by the infrastructure commission, several prominent economists, MPs across the political spectrum and affected citizens as being restrictive and often just plain weird. But the big unanswered question was: how did they reach such controversial conclusions?

This week, for the first time, independent hearings panel chair Trevor Robinson fronted up to Wellington city councillors. After four hours of questioning over two days, its finally becoming clear how the panel reached its unusual findings.

Almost every weird decision, every strange conclusion, every move to reduce housing capacity, all comes back to one person: Australia-based economist Dr Tim Helm.

Helm was hired by the Newtown Residents’ Association, the Onslow Residents Community Association, and the Wellington’s Character Charitable Trust. He argued “zoning for additional capacity does not change housing supply or affordability”. He’s one of the only economists in the world who has taken that stance. Helm’s evidence included self-written blog posts claiming Auckland’s upzoning didn’t lead to more housing – a position which has been debunked, according to Motu economist Stuart Donovan.

Councillor Rebecca Matthews asked if it was appropriate for Helm to cite his own blog posts as evidence. Robinson revealed he hadn’t actually read Helm’s research. “I wasn’t aware that Dr Helm cited a blog post. I can’t recall him doing that. I certainly can’t recall reading it, I’m pretty sure I didn’t.”

Robinson said Helm’s oral testimony convinced him the jury was still out on whether upzoning caused housing growth. “Whatever may or may not have happened in Auckland, we didn’t have any evidence before us on how, or why, or the extent to which it was relevant to Wellington … We saw it as a red herring.”

Helm said the proposed District Plan already provided more housing capacity than was needed, and any extra would be “like pushing on string”.

The economist for Kāinga Ora, Mike Cullen, argued a more mainstream view: enabling even more housing above and beyond what the plan already provided would likely result in more competition, more diverse developments, and lower prices.

Cullen wanted the council to take a “more liberal than restrictive view” of new housing. “In planning for growth and development, density is regarded as a good thing if applied in these areas, with the further point that all else being equal, more density is better (economically) than less density.”

Cullen said the District Plan was “too low and at risk of not meeting demand”. Wellington already has a housing shortfall of 10,222, to add to the 36,000 new houses it is projected to need over the next 30 years, meaning 93% of all possible sites would need to be fully developed just to keep pace with population growth.

Robinson told the council he found Helm’s evidence more compelling than Cullen’s. “We accepted Dr Helm’s economic evidence, that because so much development had been enabled in the plan already, adding more would make no meaningful difference.” Helm’s argument that enabling further supply wouldn’t improve affordability “appeared credible to us,” Robinson said. “I put the contrary propositions to Mr Cullen and his answers appeared less credible to us.”

Matthews asked whether it mattered that Helm was arguing a fringe economic position, which is “out of step with the entire profession’s view.”

“We did not study the tomes that have been written by economists trying to analyse this,” Robinson replied. “We did not have evidence of ‘what is the prevailing economic view’, we had competing economic evidence, and we had to make a judgement on which we thought was better founded. In terms of Dr Helm being out of step: in my mind, it’s not a numbers game, it’s who has the best analysis.”

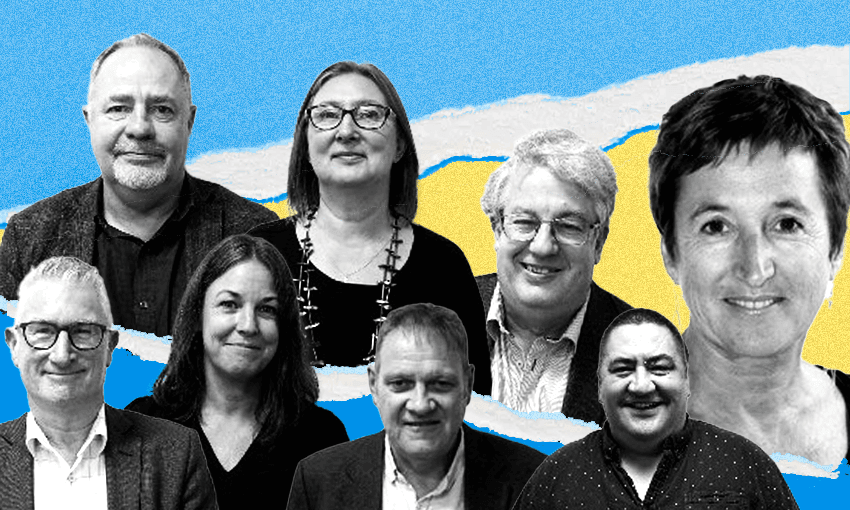

Robinson is not an economist. None of the eight panel members are economists. Despite that, the panel felt it was responsible for deciding whether the laws of supply and demand apply to housing, and used it to make sweeping decisions about the future of housing in Wellington.

The panel latched onto Dr Helm’s argument that extra capacity wouldn’t improve supply or affordability. It was the key justification for the decision to expand character areas – because excess capacity meant it wasn’t necessary to densify the inner suburbs.

The same argument was used to reject this entire list of upzoning requests from Kāinga Ora and other private developers:

- Increase the medium density height limit from 11m to 18m.

- Increase the high density height limit from 22m to 29m-43m, depending on location.

- Add high density areas to Aro Valley.

- Make most of Newtown a high density area.

- Make Berhampore a high density area.

- Make most of Mount Cook a high density area.

- Make Oriental Bay a high density area, up to 36m.

- Make Mount Victoria a high density area.

- Increase the height limit in Island Bay from 14m to 18m.

- Increase the height limit in Tawa from 21m to 29m.

- Add high density zoning south of Victoria University, Kelburn.

- Increase the height limit in the Johnsonville town centre from 21m to 36m.

- Upgrade Takapu Valley to a medium density zone.

- Upgrade five other new residential developments from low to medium density zones.

If the panel had sided with Cullen’s view, it could have treated these requests as a cherry on top of the housing sundae, extra wiggle room to make sure Wellington was doing absolutely all it could to address the housing crisis. Instead, it sided with Helm’s view, and decided there was no point doing any of it.

All this bears the question: if the panel’s decision about the economics of housing was so important, why did only two economists give evidence?

One person who submitted on the plan told The Spinoff it never occurred to them to find an economist to support their pro-density argument. They assumed the idea that more housing capacity leads to more housing and better affordability was a basic, widely accepted fact, rather than something they had to prove.

Other highlights from the War for Wellington:

Panel chair admits he mischaracterised Generation Zero

Youth-led climate change movement Generation Zero and its representative, Marko Garlick, had a tough time with the panel. The group’s attempts to push for denser housing in the city centre and near public transport were repeatedly rejected and dismissed.

The panel even snuck in this snide, climate-change-themed dig: “Dr Helm described the surplus capacity enabled by the proposed District Plan as “an inconvenient truth” for those, like Mr Garlick, who told us that planning controls play a dominant role in housing affordability. We consider that quite an apt description in the circumstances.”

One part of the panel’s reports said Garlick had “provided no details or analysis” to show upzoning would increase housing supply or affordability. This was not true. In both his written statements and oral evidence, Garlick provided several studies to back up his statements.

Councillor Ben McNulty asked Robinson if this was a mischaracterisation. “It might be,” Robinson admitted. “I would need to listen again to the tape. If I have misdescribed Mr Garlick’s evidence, I would apologise to him. I, and my colleagues, wrote our reports based on the notes we took and the written evidence we had … I relied on the notes I took of what Mr Garlick said. If those notes were in error, then what I contributed to the report was probably an error.”

The Spinoff identified a second instance where the panel misrepresented Generation Zero’s evidence.

The panel’s report on character areas says “Generation Zero told us that rents in inner-city suburbs would remain high” even if the areas were upzoned. But no one from Generation Zero ever said that. In fact, Garlick told the panel the exact opposite – that upzoning the inner suburbs would “provide greater opportunities for residential development … thereby reducing inner-city housing prices” (my emphasis).

Walking is still an impossible mystery

One of the strangest events of the whole District Plan process was the panel’s decision to reduce the city centre walking catchments, where six storey apartments are allowed by default. The panel refused to consider census data showing the areas where Wellingtonians walk to work, because the census had only asked how people get to work and didn’t ask how they got home.

Several councillors were bemused and asked why it was so hard to believe someone who walked to work would walk home. Robinson doubled down on the panel’s decision. “There was an evidential hole,” he said. “The question was how you get to work, so how people get home is a big question upon which we have no meaningful evidence, which left us in something of a quandary.”

Robinson revealed the panel also dismissed the council’s own statistical modelling of walking catchments. “All the empirical data was based off fit trampers who had Fitbits, because they were the only ones who could provide the data, and it was skewing the end results,” he said.

That claim prompted Sean Audain, the council’s strategic planning manager, to interrupt Robinson. As a council officer, he couldn’t directly say Robinson was wrong, but he diplomatically urged councillors to read the report he was referring to, and hinted at how councillors could overturn the panel’s findings.

“Walkability has a range of definitions in international town planning, and the weight you decide to place on different forms of evidence would be the basis of an amendment, should you wish to make one,” Audain said.

It turns out the report was based on Strava, not Fitbit, and it was based on regular commuters, not trampers. It acknowledged the data was biased towards faster walkers, but balanced that out with 48 pages of mathematical modelling and dozens of other walking studies to account for the speed of average walkers.

What will happen next?

The independent hearings panel is still gradually releasing its recommendations, though the most important decisions about housing are out already. The remaining reports focus on niche issues like earthworks, noise, and subdivisions.

The recommendations of the independent hearings panel are not final. Wellington city councillors still have the chance to make changes to the District Plan in a meeting on March 14, as long as they can get a majority vote for their amendments. Any changes the council makes will need to be signed off by the minister for the environment.

How to follow along

If you want to stay on top of everything that happens throughout this process, subscribe to The Spinoff’s War for Wellington newsletter. Every week, we’ll send a roundup of the most important stories about the District Plan process and the future of housing in Wellington. It will include highlights from our own coverage, perspectives from experts and activists, and the best reporting from other media around Wellington.