Developing curriculums to include mātauranga Māori is a slow process – but it’s worth the wait, writes Melisa Chase.

Nāku te rourou, nāu te rourou, ka ora ai te iwi – From my contribution, and your contribution, we will flourish.

It’s an interesting time in education with the recent inclusion of mātauranga Māori into the curriculum. I’m fortunate to work at a kura where the complexities of the recent inclusion of mātauranga Māori in the curriculum did not cause the leaders to succumb to their fears. Instead they chose to talk to the right people, make it a priority and problem solve ways to authentically move forward. Of course it hasn’t been roses, sparkles and sunshine but we are committed to transforming mindsets of teachers and students by providing equal space for mātauranga Māori into our teaching practice, in order for it to permeate our classrooms.

Titiro whakamuri, ka kōkiri whakamua – Look back and reflect so we can move forward

It’s a stark contrast to my childhood school days. Growing up in the 70s and 80s was a different landscape. We enjoyed long hot summers, one cent lollies, 75 cent Big Macs and dial telephones that were stuck on the wall. As teenagers we would sneak away on a Saturday night to Papa’s Place, where there was breakdancing, bopping and lots of hip hop music. Everything was different, even our language: we called each other muppets or eggs, chewing gum was chuddy, being hearty was having the guts, and school shoes were Charlie Browns or Nomads. If you had caramel Nomads, you were a flash fulla. I had black Charlie Browns because they were cheaper, but I always dreamed of those (very ugly) Nomads. Primary and intermediate schools’ focus was predominantly on reading, writing, arithmetic, arts and sports. High schools offered more subjects, and although the curriculum and school responsibilities were less demanding than today, they neglected to offer a balanced view of New Zealand history, thus erasing Māori knowledge and replacing it with homogeneity to the majority and invisibility to the minority.

If we go back a further 130 years to 1840, I know my tupuna (ancestors) agreed to an interdependent country that would include our history, but this is not what I was offered when attending school. I imagine they expected I would also learn about our migration story that began centuries before our arrival to Aotearoa in the 1200s. I’m sure they wanted me to know that I come from a whakapapa of the best navigators in history because of the knowledge and state-of-the-art technology required to traverse the largest ocean on the planet for three weeks in one sail, discovering islands along the way. This was during a time the rest of the world believed if they sailed too far, they would fall into an abyss. My tupuna would have anticipated that my learning would include the difficulties they had acclimatising to an untouched island and how they settled in with the land. Obviously I would be able to contribute to the lesson, sharing where my waka Te Arawa and Tainui landed, and how my iwi adapted to the whenua and puna wai ariki (sacred waters) of Taupō-nui-a-Tia and Karapiro. I’m sure my classmates would have been fascinated with how far back my knowledge and connection to the land goes, exceeding theirs by hundreds of years.

Maintaining our own language, spiritual and medicinal knowledge would’ve been areas that my tupuna naturally considered non-negotiable. Learning what plants to use for health issues, which Atua provides the kai, where to find beneficial kai sources and where to avoid. I should have learned about why we read the environment and stars to harvest, cultivate and replenish the earthly resources. And let’s not forget the sacredness of spiritual intelligence, procreation, parenting, kaumatua and the value of my ikura (menstruation). What about the many brutal inter-tribal wars that occurred all around the whenua (land) because I am a mokopuna (descendant) of warriors? But the cream of the crop of important information would have been our version of the arrival of Abel Tasman in 1642 and then Cook in 1769. I mean, those arrivals would have been the laughter of the island, not just because of the ridiculously clunky, slow boats they sailed in, but also the low intelligence of these peculiar, smelly people.

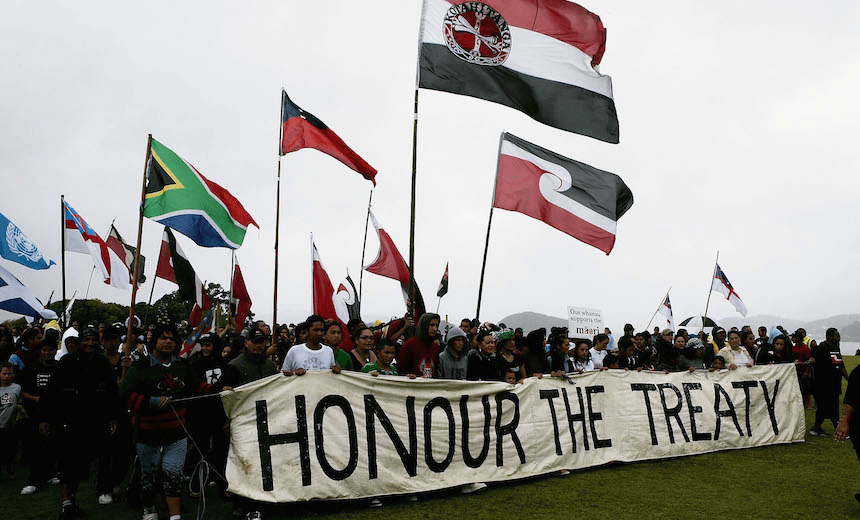

So, yes, it’s about time mātauranga Māori was included into the curriculum, because our contribution to this land is even more vast than what has been mentioned above. Te Tiriti was signed as a declaration of partnership, but instead we have built separate communities who are blissfully ignorant of the land we call home where newer New Zealanders occupy more space than Māori. Māori are caught between the dichotomy of being proud to be Māori and the shame of being Māori, so therefore it is safer for me to be less brown and more white. In Becoming Pākehā, John Bluck wrote “Māori have no choice about being bicultural. They have to operate in what is still a dominantly Pākehā world. Pākehā don’t have to. They can still live here as though Māori don’t exist.”

Tūwhitia te hopo, mairangitia te angitū – Eliminate the negative, accentuate the positive.

It’s been two years since I was invited by management to engage in conversation around MOE’s new (but vague) mātauranga Māori and mana ōrite (equal status for Māori knowledge) initiative. I won’t lie, I was just as confused as my colleagues and I am the te reo Māori teacher. One of my roles as an in-school Kāhui Ako leader is to deliver mātauranga Māori professional learning to my kura. To set the scene further for you, Māori are a minority, both students and teachers. Are you reading between the lines?

Confronting my own lack of knowledge of Māori history and deep seated insecurities around my Māori-ness and indigeneity caused me to pause. The erasure of Māori knowledge from the landscape of mainstream New Zealand was delivered through colonisation and fortified in every home. My parents, brothers and I as well as most of our offspring, are products of this.

In a short space of time, myself and colleague Ruth Richardson delivered the first of many planned Mātauranga Māori professional learning sessions to our staff of 85. To be clear, I am not advocating for the erasure or replacement of NZ History, but I am advocating for a wave of change by the inclusion of indigenous stories. I am insisting they sit side by side. I am not saying, “You are wrong.” I am saying, “I am right too.”

We ran sessions over three weeks and we used Matariki to frame the learning: Waitī and Waitā. Teaching traditional weaving, Matariki & Rehua – looking at the healing powers of pepeha and whakawhanaungatanga, ururangi and waipunarangi. Considering the implementation of te reo Māori in science, tupuanuku and tupuarangi –seeing the world through Māori eyes, an academic approach. And finally, hiwa-i-te-rangi – looking at how mātauranga Māori has evolved over time.

That’s a lot right? So, how did we go?

Everett Rogers’ Diffusion of Innovations Theory posits that when new innovations or behaviour are introduced to a community, everyone falls into five different adopter groups. The percentages are gathered according to the time it takes to adopt new innovations or behaviour. The groups are as follows: 2.5% are the innovators (the movers and shakers), 13.5% will be the early adopters (the enthusiastic go-getters), 34% are the early majority adopters (the FOMO), 34% the late adopters (If I have to!) and the 16% laggers (they are not buying what you are selling!). These percentages create an ‘S curve’ and within the curve are “chasms” which are the gaps between each group representing the difficulties of any group in accepting change.

As a reflective practitioner, I would say our percentages do reflect the Diffusion of Innovation Theory, and I would also agree with Simon Sinek when he suggested that the innovation be aimed toward the early adopters as they will create the movement. The late adopters will come along because they have to, and as for the laggers, they will always exist. Let’s be straight up here, implementing Mātauranga Māori into mainstream schools is messy and uncomfortable, and when change is required, resistance and fear is guaranteed.

Regardless of where people are grouped or what phase we are in, I am not discouraged by these metrics because this has always been about honouring treaty partnerships, and if there is one thing Māori know, since the signing of He Whakaputanga (Declaration of Independence) in 1835, we have always been willing and patient participants at the table.

This article was written as part of the Education Perfect Fellowship, which supports teachers doing post-graduate studies to investigate critical issues in education.