The force that underpins the oppression of African Americans is the same force that underpins the oppression of Māori and Pasifika, writes Laura O’Connell Rapira.

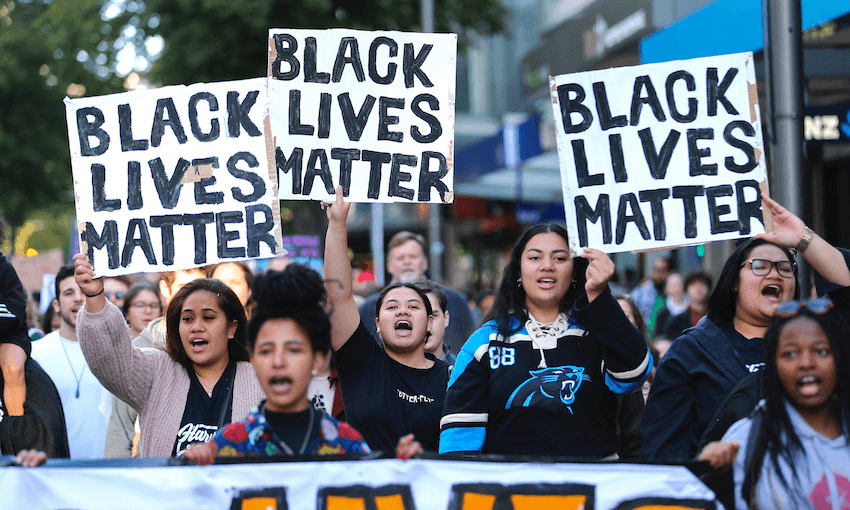

In honour of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and every other Black and brown life that has been taken from us by racism and racist institutions, hundreds of thousands of people around the world have taken to the streets to say #BlackLivesMatter.

We grieve for the lives that have been taken from us and we send our karakia and our aroha to their whānau and friends. We also pledge our commitment to do all that we can individually and collectively to build a world where Black and brown people are not killed because of white people’s racism.

A future where every single person – regardless of the colour of their skin – is safe and free. A future where police – if they exist at all – help people instead of harming them. A future where every Black person, every indigenous person, every disabled person, every trans person, every Black trans person, every queer person, every poor person, every Muslim, every refugee, every young person, every kaumātua, and every person of colour is honoured, valued, safe and free.

I believe this future is possible but only if people like us continue to use our power, our vision and our courage to make it so.

Over the last nine months, I have had the good fortune of working with an incredible group of humans to stop the militarisation of police in Aotearoa. Last week the new police commissioner announced that the use of armed police would not continue. I mihi to Andrew Coster for that decision. When that announcement was made, a weight was lifted from our shoulders and hearts.

But I also think it’s important we acknowledge that decision was the result of months of passionate and dedicated campaigning from everyday people.

People like Josiah, Melissa and Guled, who launched and led a petition opposing armed police because they knew the racist history of policing toward Black, Māori and Pasifika communities, and wanted to prevent harm towards their whānau.

People like South Auckland councillor Efeso Collins who called out the trial immediately because he knew it was the people in his community who were put most at risk of being hurt or killed by police with guns.

Organisations like the Mental Health Foundation and JustSpeak, who published open letters calling for mental health and de-escalation first strategies instead of armed police.

People like the 1,155 Māori and Pasifika people who shared their stories and perspectives with ActionStation on the use of armed police: 78% of whom had experienced or witnessed racism from police and 92% of whom agreed we needed to prioritise mental health and trauma-informed responses over police with guns.

Journalists like Mihingarangi Forbes and Māni Dunlop, who used their platforms to amplify those voices so that they were heard loud and clear in the halls of power.

People like Emmy Rākete and the Arms Down campaign, who organised over 4,000 people to make submissions or phone calls to stop the trial of armed police.

People like Muslim leader Anjum Rahman, who publicly condemned the use of armed police and the use of the Christchurch terror attack as the rationale for them.

Researchers like Pounamu Jade Aikman, Ngawai McGregor, Anne Waapu and Dr Moana Jackson, who reminded us to remember our history, its impacts on our present and to imagine a better future.

People like Julia Whaipooti and Tā Kim Workman who took an urgent claim to the Waitangi Tribunal stating that armed police were in breach of Te Tiriti.

Artists like Māori Mermaid who used her talents to create powerful images that showed a different way of policing was possible; images that hundreds of people then crowdfunded into giant street posters near Wellington, Auckland and Christchurch police stations.

I share these stories because I think it’s important to remember that social change does not happen on its own. It happens when ordinary people come together to use our power, our networks, our creativity, our talents and our time to pull a more just and beautiful future towards us.

We are gathered here today in honour of every Black and brown life that has been taken from us by racism and racist institutions. We gather because we know that the force that underpins the oppression of Black people in the United States is the same force that underpins the oppression of Māori, Pasifika, and Black folk here.

In colonised countries around the world – the US, Canada, Australia and New Zealand – it is Black, brown and indigenous people who are most likely to be hurt or killed by the police or end up in our prisons.

And so the question cannot be: why are so many Black and brown people going to prison, as if we volunteered to put ourselves there. But instead: why do so many coloniser governments keep locking brown and black people in the cages we call prisons? Why do so many coloniser governments keep employing police officers that hurt and kill Black, brown and indigenous people? And what are we going to do about it?

In Minneapolis, where George Floyd was killed, the government has pledged to defund police and redirect funding to proven, preventative responses and community-led services that invest directly in people and communities.

In New Zealand, where the government spends more money every two years on prisons than it has the entire history of Treaty reparations (not settlements, because treaties are meant to be honoured, not settled) this is an example we need to follow here.

We have the highest incarceration rate of indigenous women in the world. Ngāpuhi, the iwi that my koro is from, is the most incarcerated tribe in the world.

Imagine if instead of spending billions locking up Māori, the government gave Māori those billions so we could unlock our own freedom.

Imagine if we collectively decided that the police’s slogan, “Safer Communities Together”, meant that we funded teams of de-escalation specialists, mental health experts and social workers to help people instead of armed police.

Imagine if we collectively decided to prioritise help over handcuffs, prevention over punishment, and life over death.

I believe a world like this is possible. But only if people like us continue to use our collective power to make it so. For some of us that means having courageous conversations with our family members and friends. For some of us, that means donating to kaupapa led by and for Black and indigenous people. For some, that means learning more about our racist history so that we’re not always asking people of colour to do that work for us. For some of us, it means hiring differently or developing explicitly anti-racist policies for our workplaces, our churches, and our institutions.

For the police commissioner, it means recognising the need for the community to be meaningfully involved in the decisions you make. It means recognising the harm that police have done, and still do, to Black and brown communities and taking reparative action.

For the justice minister, Andrew Little, it means following through on your promise of justice transformation if you are elected again. What you choose to do with your power – for my people and my whānau – is life or death. I want to see Labour acting like it if they get elected next term.

As Martin Luther King Jr famously said, “injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere”. We must do all we can to stand in solidarity as we work for a future where all people everywhere are honoured, safe, valued and free.

This piece is an adaptation of kōrero Laura O’Connell Rapira delivered at Black Lives Matter rallies and vigils in Wellington recently.