Ian Fraser on a new, brilliantly told account of the famous 1862 killings on a remote track between Nelson and Marlborough.

It’s hard to imagine anyone telling the story of colonial psychopath Richard Burgess (1829-66) better than Wayne Martin in this gripping and vivid history.

Step by step, Martin shows the leader of the Burgess Gang following the money to be had in the 19th century gold rush in Otago and the West Coast, ending in a series of crimes “unmatched in colonial New Zealand for their scale and cold-bloodedness”. He means the Maungatapu Murders, among the most famous killings in New Zealand history.

There was nothing heroic or romantic about the murders. As Martin acknowledges, “No trace of redemption or gallantry has clung to the legend of the Burgess Gang, as it did with contemporary New Zealand bushranger Henry Garrett or Australia’s Ned Kelly.”

This is striking, because from the American West to the Australian Bush, the history of the frontier takes the form of a Beggar’s Opera. The rules are that the bad guys get shot up or lynched in the end but, like the devil, they invariably have the best tunes. They’re the characters who add a dash of brimstone and charisma to the saga of rape and pillage which is the real story of how the West was won.

There were other bad guys who took land and other people’s stuff by force of arms or under cover of the law. Mostly they rose without trace. They endowed galleries and libraries, ran for office and were duly admitted to the national pantheon of hypocrites.

But we stubbornly prefer the figures who didn’t cover their tracks or redeem themselves with good deeds once they were old and past it. They come down to us fresh-minted in movies and country songs and novels by masters like Larry McMurtry and Peter Carey. We’ve even found ways of placing them on the right side of our historical morality plays. Jesse James, we’re lectured, resorted to bank robbing not just because the banks were there but because it allowed him to go on fighting the Southern cause even after the cause was lost – continuing the Civil War by other means.

Richard “Dick” Burgess, though, was just a bad guy, although he did have a fancy prose style. Awaiting execution, he produced a 47-page memoir, eventually published by the Lyttleton Times, as the “Life of Richard Burgess, the Notorious Highwayman and Murderer, written by himself, while in prison, shortly before his execution, which took place at Nelson, NZ, on the 5th day of October, 1866.” Mark Twain, briefly in Nelson on a lecture tour at the turn of the century, read it and hailed it as “perhaps without its peer in the literature of murder”.

Born illegitimate in 1829 in London’s Hatton Garden, Burgess grew into a toughened young criminal with a pronounced streak of cruelty. He earned his final expulsion from school when he punched the end of a pencil, which a classmate had inserted in his own nostril sharp end up, driving it deep into the boy’s nasal cavity.

Martin follows Burgess through the serpentine layers of Britain’s Victorian penal system. Transported to Melbourne, he found himself in a rare position to escalate his life of crime – for, as Martin observes, “crime was Hill’s drug”.

After a period in the notorious prison hulks of Hobson Bay and a stint in the austere setting of the new model prison at Pentridge, he eventually made his way to New Zealand. He arrived at Port Chalmers in 1862 in good time for the Otago gold rush, which had boosted Otago’s population from 691 in 1860 to more than 30,000 the following year.

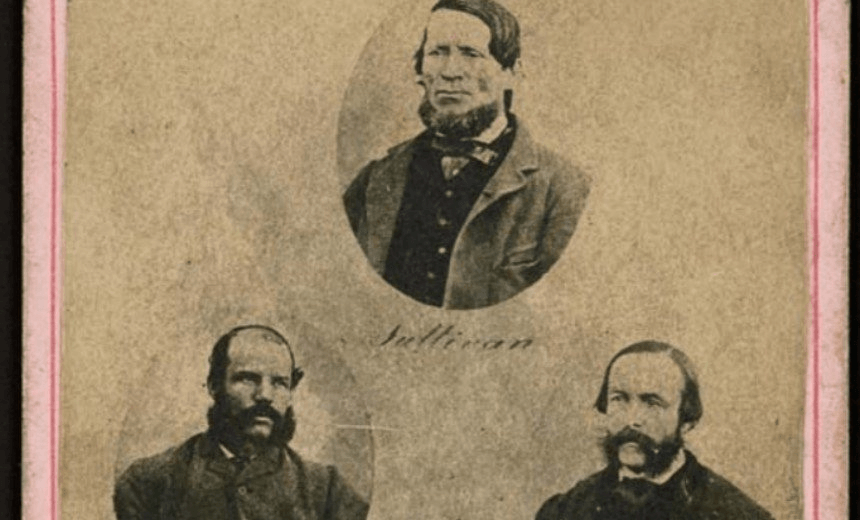

His preying on miners reached its homicidal conclusion on the rugged, isolated Maungatapu track between Nelson and Marlborough. In two days, June 12 and 13, 1966, Burgess and his gang lay in wait, and robbed and killed five men.

First there was a flax grower. The next day, four businessmen were strangled and shot. George Dudley, a storekeeper, was murdered first. Burgess’s gang led him off the track and into the bush before they strangled him. The original plan had apparently been to strangle all four victims to avoid the sound of gunfire. But Dudley had taken an inconveniently long time to die, so they decided to shoot the other three. Again, they took their victims well off the trail to shoot and stab them.

The gang reconvened in Nelson, bought smart new suits with the gold they had stripped from their victims, ate and drank well – and hatched a plot to rob the Bank of New South Wales. This would entail one of them taking a steamer to Melbourne to acquire disguises, including false beards, moustaches and wigs (yes!).

Martin: “They planned to enter the bank just before closing time and tie up and gag the male staff. [Thomas] Kelly would quieten any women present by putting a knife to their throats. When all were secure they would take the victims one by one into another room and force strychnine down their throats. Devised mainly by Kelly, the plan called for one man to be led away, killed and buried so that he would be blamed for the murders.”

Then it all went wrong. Rumour and gossip hardened into fact as the dispersed pieces of the bloody puzzle came together and colonial Nelson closed ranks against the killers. Several thousand Nelsonians had already filed past the bodies of the four men, laid out in the town’s engine house, and nearly 3000 mourners had gathered at the cemetery for the burials.

The final act of the melodrama unfolded on the gallows built in the exercise yard of the gaol. Burgess, the leader of the gang, declared in ringing tones, that “although going to that fatal scaffold, I feel as happy as if I were going to a wedding this bright and beautiful morning. This is the morning of my death but it is also the morning of my birth into another and brighter world, where sorrow shall pass away and all tears be wiped from the eyes.”

Then he raced up the stairs of the scaffold and, holding a small bouquet of flowers, strode to the drop, seized the centre rope, kissed the noose and announced that he “greeted it as a prelude to Heaven”.

I doubt he believed a word of it but it must have been an electrifying performance.

Murder on the Maungatapu: A narrative history of the Burgess Gang and their greatest crime (Canterbury University Press, $45) by Wayne Martin is available at Unity Books.