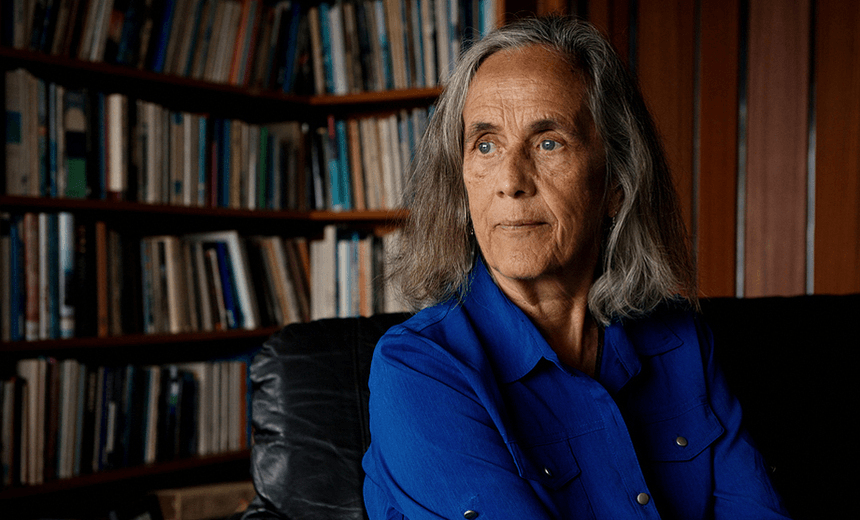

All week this week we feature a book or author nominated in next Tuesday’s Ockham national book awards. Today: Holly Walker is given a rare interview with fiction finalist Patricia Grace.

Since becoming the first Māori woman to publish a book of short stories in English in 1975, Patricia Grace has always made a commitment to tell the stories of ordinary people and their ordinary lives. That just happens to be a political act when those people haven’t had a voice in literature before, and a revolutionary act when their ways of telling stories push the boundaries of conventional literary form.

Grace’s 2015 novel, Chappy – her first in 10 years – tells the story of a Japanese stowaway who finds himself integrated into a small Māori community before running away from his family to avoid capture as an “enemy alien” in WWII. It’s warmer and gentler than her earlier work, but no less political in its expectation that readers see Māori communities for what they are: strong, loving, resilient.

It’s shortlisted in the fiction category in next week’s Ockham Book Awards. Ahead of the ceremony in Auckland, Grace gave a rare interview from her home in Hongoeka Bay, Wellington.

I read an interview you did with Sue Kedgley way back in 1989 for a book called Our Own Country. It was a book of New Zealand women writers talking about their writing and their lives. Can I read you something you said in it?

Oh my goodness. Are you sure?

It’s not embarrassing. You said, “I think everything that has happened to me in my background and culture and upbringing is part of me, and is something I can write about, and that includes my parents and my extended family because I am part of my ancestors and part of my descendants.” That seems to apply to your novel Chappy, and to the way you show us the title character, the fact that he doesn’t come from right inside you.

Yes that’s right. The story came about because of someone my husband told me about. My husband was from Ruatoria, and he told me about a Japanese shopkeeper that they’d had, who was married to a local woman, and who was very much part of the community and very well loved and liked by the community, but he was taken away during the Second World War and interned on Somes Island as an enemy alien. That started me wondering – my story Chappy isn’t about that man, but it is about a Japanese man ending up in New Zealand – and I wondered how that person got here.

I read one review that said the book was harking back to a time in the past when family ties were strong, and communities were close, using the label of nostalgia. How do you respond to that description?

Oh, nostalgic. Oh well, I think that’s alright. Maybe it is. I don’t know.

See, I didn’t think it was. I thought you were describing communities that were still strong, and family ties that were still very present.

Oh yes, I think that too. I think our family ties are very strong, still.

The suggestion was I guess that that’s no longer the case. I thought you were quite purposely setting out for Pākehā readers as well as others, subverting some perceptions about Māori family life and the strengths of bonds in those communities.

My aim has always been to write about ordinary people and their ordinary lives. That’s what I started out to do and I think that’s what I still do. The ordinary lives that people don’t hear that much about.

And working lives. Work is a very strong part of this novel, isn’t it, the different kinds of work your characters find and build themselves around.

Yes, and people today also value having jobs and working hard, but we don’t hear much about the ordinary lives of ordinary people really, in the media.

That same reviewer [Nicholas Reid, at Stuff] said “it makes no difference to Pākehā readers that the milieu is a specifically Māori one.” Did he kind of miss the point?

I’m not disagreeing or agreeing. I just live in my own community, which is a very functional marae-based community, and a lot of that is inspirational for me, the fact that we live as families, the fact that we live as a marae community, and that we have our distinct cultural lives here where I live. Also we operate outside of our community as well, in our jobs and our professions, whatever they are. I don’t know what that means to other people. When I’m writing, I don’t really have readership in mind, because I think that would be something that would limit me, if I tried to think who was going to be reading, and what effect it might have, or any of those things. I don’t. I just tell my story, and do it in the best way that I can, and hope that people will read it. So if I’m aiming it to anyone it would be to people who read, you know, readers who want to read it. Not to Māori particularly, not to Pākehā particularly, just to readers who want to read.

Do you see your writing as political?

Yes I do, now. I never used to. I was just writing about ordinary people and their ordinary everyday lives, and land issues, language issues, health issues – all the issues to do with Māori people, part of those ordinary lives. But then when you set them down on paper, I’m told they’re political, that’s a political aspect.

Well particularly early in your career when people hadn’t ever read anything like that, it probably couldn’t help but have some political impact on people who were reading those kinds of stories for the first time.

Yes, I think if you’re writing about marginalised people who haven’t had a voice in literature or wherever, then I suppose it’s political, do you think?

Yes, I think so for certain. It’s interesting that you say that earlier in your career you weren’t aware of that as much as you are now, because in some ways, for me, reading your early work, particularly Potiki, that packs a really strong political punch in the powerful way in which that unwelcome development, and the impacts it has on the community are portrayed.

Yes, that’s when it came home to me, really. It was described as a political novel. I hadn’t set out for it to be, and didn’t know that it was. I still thought I was writing – and I was – writing about the lives of ordinary people, and their concerns and so forth, and the things that had happened. And in the place where I live, which is on ancestral land, in my own community, there had been threats on our land year after year, really, of companies wanting to come and make a marina, or container port, or wanting a coal fired power station to be built here, wanting the place developed with shops and roads and so forth, and planning going on behind our backs, and all that sort of thing that we’ve had to be strong and stand against, and not sell our land and not let our land be used.

Living with that kind of threat was part of that ordinary life.

Yes it was, it became ordinary. It wasn’t even overbearing if you know what I mean. It was just ordinary that we were here to stay and that was it. So that’s where the story of Potiki came from, and it’s actually set here where I live.

And of course that turned out to be very prescient – I don’t know if we could really say it was life imitating art since all along as you say you were just writing about the ordinary threat that was humming in the background of your community – but of course you ended up fighting a massive roading development [the Kapiti Expressway] on your land, and you won that fight. Was that like writing a different ending for that story?

Yes, well people say to me, am I going to write a new novel about that, and I kind of say “I’ve already written it!” I wrote it when I wrote Potiki. But yes, that was something that the family and I did was fight for that land, and fight for it in the Courts, and I suppose even to my surprise, winning that fight. But I really went into it thinking that if we lose this, at least my grandchildren, our grandchildren will know that we tried hard not to let the land go.

Of course the road is still being built, it’s going to have to be diverted around your ancestral land now, but they’re still building it. How do you feel about that? Did you oppose it altogether or was it just about keeping it off that particular land?

I opposed the motorway, but that was kind of before I got the letter to say my land was going to be taken under the Public Works Act. Because I refused to sell it, it was to be taken under the Public Works Act, and that’s what we fought against. We did it by making the land a reserve in our name. It was opposed in Court, but once it’s reserved land, it becomes inalienable, even to the Crown, and that’s what the Court found, because that is a fact. At the moment. But they’re trying to change that now.

So the fight’s not completely over?

Oh no, the fight is over, but for future people with land in that category. Well it hasn’t come through yet, and hopefully it won’t.…All through history, laws have been changed in order to take Māori land. You know, bring in a law that says “this land’s going to be used for a road” or “this land’s going to be used for recreation” and just taken. It’s as though the same thing is still happening with the Public Works Act. And much more Māori land has been taken under the Public Works Act than general land as well. So that doesn’t seem fair either.

It sounds like once it became very close to home for you, your focus shifted away from opposing the motorway itself, and you really had to focus on that fight at home.

Yes, the opposition to the motorway was already lost by then. At first, for quite a long time, I didn’t know my land was part of it. I hadn’t been approached or told. I was busy doing other things, my mother was very ill, so that sort of passed me by. I knew that I didn’t want the motorway, but I also didn’t know that my own land was in the picture, and I hadn’t been approached or told, or asked.

I also found Sue Kedgley’s 1989 book inspiring because you talked about how you found time to write in the evenings when your children were very young, even when you were still working full time as a teacher. It takes a lot of determination to write with young children. Where did that drive come from?

Really just from wanting to write, and that being my respite in a way. Having that thing that I loved to do, and to find the time for myself to enable me to do it. I wouldn’t have been able to do it without support. My husband and I were both teaching, and we both did what we needed to do in the house, we both did what we needed to do in the care of the children, and he was studying and I was beginning to write. We made that time for ourselves in the evenings by working together. The house that we lived in was part of the school grounds. Our children had a lot of freedom really, in those days. They had school fields and school swimming pools and a lot of countryside and bush and creeks and all that.

Did you find that it got easier to write as your children got older and you were able to write full time, or is writing just hard work?

It’s hard work, but it’s satisfying work, too. I’ve never gone away into a locked room. I’ve always worked on the kitchen table while the children were young. They were all around me. I did some writing during the school holidays, and writing at night. Sometimes if I just wanted to type something up I did it with them around me and they could interrupt me any time they wanted to.

You spoke about sending your early stories to something called the Penwomen’s Society, which I thought sounded intriguing. Was that a kind of writing community with other women who were writing?

Yes, although I couldn’t attend. The Penwomen’s Society was based in Auckland, and I was living up in North Auckland where we were teaching, but they had a country membership. I couldn’t go to their weekly meetings or their monthly meetings or whatever they had, but I joined in by entering the competitions that were monthly. I hadn’t really thought about other women writing; I think the most helpful thing to me was that I sent these stories in for the competitions, and they did rather well, but also the important thing was that the judges had to give full comments, and I found that very helpful.

Your books for children don’t get as many column inches in these kinds of interviews and profiles, but my kindy teacher mum would never forgive me if she knew that I’d talked to you and not talked to you about your children’s books. What made you branch into writing for children?

We used to write little readers for children when we were in the country schools, because we found that the children there didn’t really – I think they like reading alright – but they didn’t really relate to the settings and the characters that they were reading about. So we made our own supplements. Sometimes we used the children’s own little stories for those supplements, and we’d just staple them together and the kids would draw the pictures or something like that, and they loved those. I thought of trying to get those published, and made a few inquiries, I can’t remember of whom now, but the message came to me that if we were going to write books for children, to make sure that they didn’t have a New Zealand setting! I thought, well that would be pointless.

So I forgot all about that. We just went on making our own little books and so forth. Then a group called ‘Kids R Us’, a group of women, looked at this gap in literature for children where there were very few stories about New Zealand children, very few, or maybe one, about Māori children, and they wanted to publish something to fill those gaps. They had ideas of stories from lots of ethnic minorities, and asked me to write a story. And I wrote The Kuia and the Spider. I just thought about – well I had the character. I thought of a spider, and I thought of a grandmother, and I thought what they would have in common and that would be weaving. And that’s where that story came about. Then I was teaching at Porirua College when I wrote Watercress Tuna and the Children of Champion Street about the local kids.

My two-year-old loves Watercress Tuna.

I’m really delighted that it’s still being published. The Kuia and the Spider has never been out of publication, not to my knowledge anyway, it’s still going strong, which is great.

The Trolley was another big one in my household growing up, because my mum was on her own to begin with, and I think she found that quite inspirational, that plucky mother making her own Christmas presents for her kids.

There was a young – well, she was very young at the time – single parent who told me that was her favourite book. I said, “Oh, your favourite children’s book for children?” She said, “No, just my favourite book of all time.”

When I first read your work, I had one of those “aha!” moments when you realise that it’s possible to tell stories in a really different way, that you’re reading something like nothing you’ve read before. Were there writers that you’ve read that have given you that feeling?

Oh well! If I go right back to when I first started thinking I would like to write. I was 18 or 19 or so when I first read work by New Zealand writers. I don’t know why I hadn’t before that, but the books that were put before us at school were all by long-dead faraway writers, and I didn’t really know what real writing was, that it was about things that you knew about. So I hadn’t really heard the New Zealand voice in writing. Perhaps I’d read Katherine Mansfield, and some of the settings and so forth, and really enjoyed her work, but she was kind of removed from me in time, I suppose, and social class, and culturally.

And then when I was at teacher’s college, I read the work of Frank Sargeson, and that was an enlightenment, because I suddenly knew that this was what – I suddenly could hear the New Zealand voice. The idioms. You know, it was like sitting next to someone in the tram and just hearing them converse. And the penny dropped with me that that’s what real writing was. I started searching out New Zealand writers and making all these discoveries.

While I was doing that, I came across the work of Amelia Batistich, of Dalmatian origin, and I thought “oh here’s a New Zealander with a different voice”, and realised that I probably had my own voice too. So I started exploring that, and also at the same time I was starting to read works by Māori writers in the journal of the Māori Affairs department – it was called Te Ao Hou – and seeing work by Arapera Blank, Meihana Durie, and Witi Ihimaera was just starting, and Hone Tuwhare’s poems. So that all added up and made me believe that I could write, and write about what I wanted to write about, and would find my own voice as well.

Chappy (Penguin, $38) by Patricia Grace is available at Unity Books.