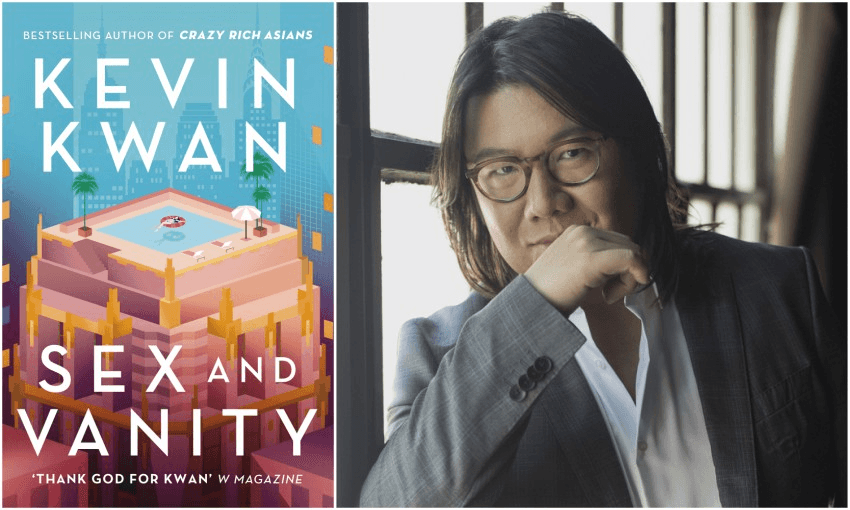

The Crazy Rich Asians author creates froth that may in fact be genius, says Sam Brooks.

Kevin Kwan’s first novel Crazy Rich Asians had the kind of success every populist author dreams of. It became a beloved bestseller, which turned into a slightly less beloved trilogy, which then turned into a blockbuster movie that was easily one of the most successful rom-coms of the past decade. When I say populist, I mean it as the highest compliment. Kwan took a world that should be highly inaccessible (the lives of not especially nice super-rich people, in a part of society that very few of us are intimately familiar with) and made it into frothy fun that was also emotionally engaging. It’s a highwire act that’s hard to pull off. Even more impressively, he pulled it off over three books in a row, heightening the emotional stakes as he upped the wealth of his characters.

Kwan’s new novel Sex and Vanity, his first since the trilogy (and, we’re promised, the first of a new series), sits within the same diamond-encrusted wheelhouse; it revolves around the problems of the super-wealthy as they fall in and out of love, trapped inside their gilded cages. It also ruthlessly satirises them and everything they stand for – which in many cases, is actually nothing at all.

The novel is split into two clean halves. The first takes place at a wedding on the luxurious island of Capri, where 19 year old Lucie Churchill meets George Zao, the improbably dreamy surfer who she starts off hating and is then, yes, infatuated with. The second half picks up a few years after the Capri affair, with Lucie in New York and intertwined with one of the most eligible bachelors in the world, Cecil Pike (has there ever been a tolerable Cecil in a book?). The course of true love ne’er did run smoothly, but having a couple billion to help you along the way never hurt.

If the plot sounds familiar, you’re either an English major or you really like Merchant-Ivory films, because yes, it is the same plot as E.M. Forster’s A Room With A View. To call Sex and Vanity a riff on Forster’s masterwork would be an understatement; it’s a riff in the same way that ‘Ice Ice Baby’ “samples” ‘Under Pressure’. No, Sex and Vanity is essentially A Room With a View with designer gowns, luxury cars, and social media. This isn’t a dig against Kwan or the novel – if you’ve got bones as strong and tragic as the ones that Forster set out, you might as well use them. (It’s worth noting that Kwan says that he was inspired by both the novel and the 1985 film, which I’d wager more people are familiar with at this point. Forster’s great, but Helena Bonham-Carter with the wind in her hair is a lot more fun.)

While nobody would describe A Room With a View as a comic novel, Sex and Vanity definitely is one. Kwan’s target is, as always, the super-rich, the crazy-rich, or the rich-crazy. The kind of people who introduce themselves last name first, first name second – and indeed, every character in the book is succeeded by a list of where they’ve gone to school; the protagonist herself is introduced with the bracketed (92nd St. Y Nursery School / Brearley / Brown). The only person that remains unskewered is Lucie herself, but everybody else, from Lucie’s annoying cousin Charlotte, to the Sultanah of Malaysia, is fair game. Kwan’s humour works best when he sits omnisciently over his entire cast, which sprawls into not just Lucie’s extended family, but her entire social circle. Take this exchange between Charlotte and Mordecai, an erstwhile interior designer/art historian at the party:

“What do you do, Ms. Barclay?”

“I’m an editor at Amuse Bouche.”

“Ah, Amuse Bouche. Super magazine, superb.” Not as good as Bon Appetit, but perhaps I can sell her on my idea of writing about Empress Josephine’s obsession with iles flottante.

“Thank you,” Charlotte responded. I’m not going to ask him what he does. It’ll drive him nuts, and he’ll tell me within two minutes.

The novel is full of this kind of jab – everything that every character says about anybody else ends up saying more about them. It’s enormously pleasurable for the reader, and Kwan feels like the conspiratorial host at a masked ball. Nobody knows who anybody else is, but he knows and he’s delighted to show you. He turns the blush-deep thoughts into comic gems, without ever betraying his own affection for the characters. He’s as much their friend as he is ours, and it’s only the best friends who can truly insult each other.

The genius, and I don’t use that word lightly, is that Kevin Kwan writes wealth like he’s writing a fantasy novel. The world is no more or less fantastical than Hogwarts, and Kwan’s worldbuilding is as tight as that of She Who Shall Not Be Named. He gets the reader into a world that is just far away enough that we know it’s unattainable, but we can see it all the same. It’s a world where celebrity chefs drop in and cater weddings, where a “four or five bedroom apartment” in Brooklyn is seen as a quaint downgrade, and where everything in the world is available at the click of a finger. One major plot point revolves around getting a famous Warhol star to be the guest of honour at a charity dinner, and he makes it feel as high stakes as a political coup. For as much as he makes fun of these characters, he’s a master at building a world, populating it with vivid characters, and getting the reader to invest in them and all their surfaces.

The constant dropping of names – brands, famous families, locations – can feel too much, but it’s part of the tapestry that Kwan is weaving. Keeping up with the names is exhausting for the reader because it’s exhausting for the characters. If you’re familiar with all the names, you get the extra thrill of knowing exactly why certain brands are gauche or coveted, but if you’re unfamiliar with them, it just builds up another layer of the character’s armour, another bar on the cage, nice though it may be.

It serves another function for Kwan: He drops all the names, all the references, so that when he throws them all aside we realise we’re caught up in the pretense of it. When Lucie falls in love, she falls hard, with breathless run-on sentences:

“ … she realized at that moment how much she wanted him, from the first moment she had set eyes on him in the lunchroom of the hotel to the vision of him as a godlike Apollo diving off the rock at Da Luigi, she had wanted him so desperately she could hardly breathe, gasping deeply while he shoved the heavy door closed with his foot, pressed her body against the ancient stone wall, kissing her throat, her neck, letting his mouth linger, as she reached for him urgently.

For the characters, life only becomes real when they throw the names away. Similarly, for the reader, it’s when the characters become real and their experience becomes something relatable, flesh and blood. Kwan is a master of judging when to deploy these moments, when to unburden us from the excess of the rest of the novel.

It’s a fascinating direction for the author, and so is the territory he’s plumbing. Crazy Rich Asians showed the ways in which extreme wealth allows people to leapfrog the inequalities forced on people by race, class and culture. Sex and Vanity is so much more: about how the trappings of extreme wealth don’t lift you up but actually weigh you down. It glances, not ineffectually, on the ways in which being mixed race complicates even the armour of extreme wealth, but it’s more a feint at weight than a true investigation. Your mileage will vary on whether the plights of the lovelorn rich are those you want to spend 300 pages with, even with skewering, but if you’re in the mood for escapism, then you’ll find enough nutrition in the froth that Kwan serves up.

Sex and Vanity by Kevin Kwan (Hutchinson, $37) is available from Unity Books Wellington and Auckland.