Down from Upland is a heartfelt toast to teenagers, written in the long shadow of Brannavan Gnanalingam’s Sprigs.

I want to be specific about the praise I offer. I don’t want to be praising young people just for being young. It seems odd to praise any generation for the mere fact of being. Maybe we can praise centenarians; nonagenarians at a push. But mostly, generational commentaries seem as silly as national rivalries: none of us are more divine than others because of our time or place of birth.

So, specifically I am writing in praise of the anarchic spirit of teenagers. (Not all teenagers make the most of this spirit.) I am writing in praise of their suspicion of the adult world and attempts to extract themselves from it. I am writing in praise of their bullshit detectors.

I am writing of the friendships of teenagers, founded on amazement that they stand to inherit the world.

I am not writing in the belief that the teens are our future or that they’ll not make the mistakes that we did. I am not writing of them as young entrepreneurs, under-18 sports reps or the next top model. I am not trading in teenagers as nostalgia, consolation or cipher.

Here’s the story of Down from Upland: a bullied teenager (Axle) leaves Wellington College and moves to Wellington High. He makes friends, and they’re his first real friends. He goes to a party, gets drunk, has a fantastic time but the next morning he pukes and spends the afternoon in bed.

Axle’s parents are intelligent, sensible types: they’re The Spinoff’s demographic, perhaps skewing a little older and wealthier. They’re comfortable public servants and liberal to a fault. They feel that they have cracked the code of parenting by insisting on moderation in each and every situation. The middle way. Instead of banning Axle from drinking, they supply him with a six pack of light beer.

Axle and his friends take this so-called beer and do everything they can with it to get “proper drunk”. They skull until they are bloated, swill it through a yard glass, add yeast and sugar to increase the alcohol content, and research alcohol’s evaporation point. They fail. Hence, the lark in the working title for the book: “The Undrinkable Light Beer of Bingeing.”

Down from Upland touches only a little on the worst aspects of teenagers and only then as an intro to a better life. Axle and his friends are perceptive and compassionate, though rarely when their parents are around. They dream of the world to come, but aren’t fooled by the homilies of their parent’s generation.

This novel was written in the long shadow of Sprigs by Brannavan Gnanalingam, the Ockham-shortlisted title which our Lawrence & Gibson publishing collective released in mid-2020. At the crux of Sprigs, teenage boys and their parents circle the wagons of privilege as they avoid responsibility for a sexual assault. It must have been bleak reading for parents of teen boys. On the flip side, many others said it was a book that all teenagers should read.

Down from Upland doesn’t solve those issues or try to reframe. It just isn’t a book about the worst things teenagers do. It is about the best. Fidelity and fortitude.

I went to the middle-decile South Otago High School. The school and wider community valued nature over culture, muscle and milk over mind and metaphor. All our notable alumni are sportspeople, except for Bill Manhire.

There is scant autobiography in Down from Upland but there is a homage to a friend group who made my last couple of years at high school an excellent time. I’d live those years again. Truly! And that is not just me saying “I have no regrets” or “I wouldn’t change a thing” because most people hate the idea of betraying their past. I genuinely had a great time with the friends I had in my final years at high school.

Hayden: he had the best dance moves and rhythm that we all tried to copy. He had pretty much the best taste in everything and was the one who first led me to an op shop.

Rhys: he was always optimistic and inventive, kitting out a bombastic stereo system in a Holden Commodore, but also sewing a sleeping bag into a jumpsuit to push back against the Otago winter.

Lachlan: was the first of us to look beyond our narrow white-boy taste, rightfully insisting on the brilliance of 90s OutKast well before the rest of us had outgrown punk.

Cody: the cool, quiet, weird one who had moved to SOHS from another school. His arrival heralded the coming together of the rest of us.

I write about them in the past tense. There was no tragedy that pulled us apart but we’ve all drifted away from one another. We live in different regions, some in different countries. It doesn’t matter. We were there, together, when we needed to be.

Down from Upland is fiction, though. For starters, our friend group was barely political and our parents certainly weren’t public servants. It was a time when teenagers could be apolitical: the late 90s. We were past the anxiety of nuclear war, but not yet anxious of compounding climate catastrophe.

My friends and I did drink like the kids in Down from Upland. Much too much, much too young. My parents made a deal with the woman who ran the record store where I occasionally worked. She could buy me beer, but not spirits. The deal was the inspiration for the low-alcohol deal struck by Axle’s parents. Neither deal worked. My friends and I drank Coruba, Kristov, Purple Goanna, Black Sambuca and Canterbury Cream. My stomach curdles at the memory. We also drank a lot of beer. Kids would turn up to parties with 24 packs. Tanks. In Down from Upland there are bottles of vodka lined up as big game trophies on a window sill. There are the parents who look the other way and those who provide a safe space by hosting the teens.

We had crushes, too, in real life. I mean, no shit, right? Unreal and wild crushes, intimate fantasies unconnected to any plausible reality, just a vivid wanting. And we were amazed at our good luck in eventually spending unsupervised evenings in the same room as some of these women. The same is true in Down from Upland, but it is not a coming of age novel. At least not one that features first kisses or realisations.

The school motto at South Otago High School was “Fide Et Fortitudine” but since the school didn’t offer Latin no-one really knew what it meant. Even the principal would have been mocked if he had delivered a speech on the merits of “fidelity and fortitude”.

In this short note appraising the virtues of teenagers, I have cited the fidelity of teenage friends but I have not mentioned their fortitude. Axle shifts schools because of bullying, but bullying feels like such a blunt word for the PsyOps of high school. Yes: at my school there were vicious assaults, but there were also the cruel nicknames and taunting. I want to praise those who survived both types of bullying and came out stronger. I want to apologise for every nickname that I repeated. Teenagers have to survive other teens as much as they have to survive themselves.

I look back on the teenagers who died while I was at South Otago High School and I still can’t tell what was true. Were there really accidents with guns? Were all the car crashes really made in error? I imagine people saw us as unable to handle the truth. But this could equally be speculation. Maybe there really were a lot of accidents.

In retrospect, most of my friends were counting down until we could leave. Growing up in a small town and knowing you’ll go makes for an indeterminate attitude to one’s future. My city friends don’t quite understand how the end of Year 13 looms for a country kid. It means escape, the end of childhood and the start of real life.

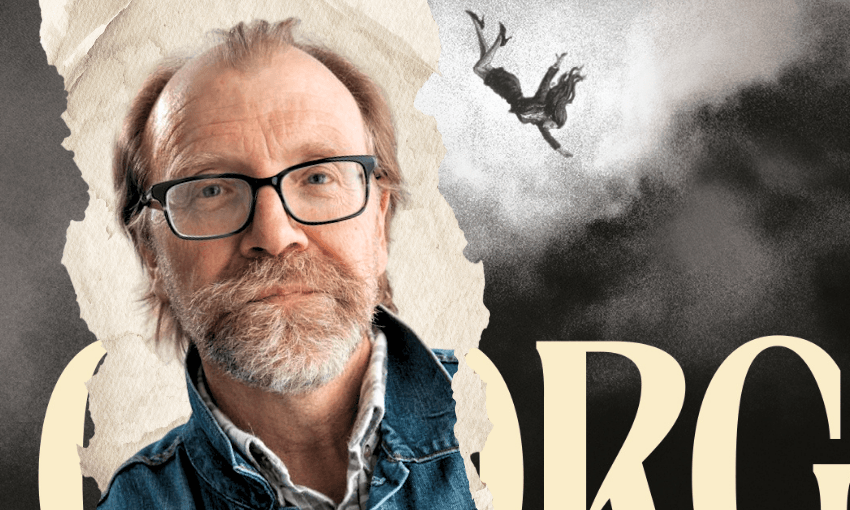

Down from Upland by Murdoch Stephens (Lawrence & Gibson, $29) is available from Unity Books Auckland and Wellington.