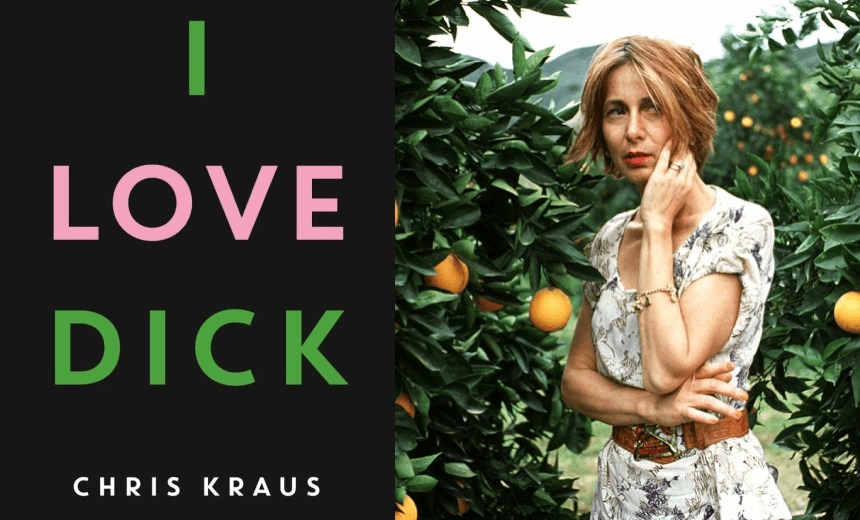

The best coverage of the Auckland Writers Festival continues right here, as the Spinoff Review of Books devotes the entire week to long, intelligent encounters with guest writers. Today: Holly Walker talks with Chris Kraus, an American writer who worked for newspapers in Wellington before creating the belated smash-hit feminist novel, I Love Dick.

Read more Auckland Writers Festival coverage from the Spinoff here

Chris Kraus’s first novel I Love Dick received a lukewarm reception when it was released in 1997, but has attracted a cult following and been hailed as a feminist classic since its re-release in 2006. As much an art project as a novel (in which every reader participates – try reading it on the train) it consists of love letters written by a character named Chris Kraus and her husband Sylvere Lotringer to a cultural critic named Dick. Yes, those are their real names, and there really was a Dick – British art critic Dick Hebdige was so angry about the book that he outed himself as the model for the character when he spoke out to denounce it. For Kraus, the lines between fiction and non-fiction are blurred at best.

The author of three other novels and two books of nonfiction, Kraus continues to collaborate with her now ex-husband Lotringer on Semiotext(e), the publishing company they co-edit with Hedi El Kholti. Though she was born and lives in the US, she spent her teenage years and early adulthood in Wellington, having Marmite smeared in her hair by the kids at Wellington High in the 1970s, and working full-time as a feature writer for the Sunday Times by the age of 17. At 21 she returned to the US to pursue an art career and spent decades making performance art and experimental films on the fringes of the US and LA art scenes. The recent revival of I Love Dick – a television adaption created by Jill Soloway (Transparent) premieres in the US on May 12 – means Kraus is finally enjoying the wide acclaim she deserves. Her 2006 novel Torpor is about to be re-released and she has a new book coming out in August.

I want to talk about your New Zealand connection. Can you tell me how you came to move to New Zealand with your parents? It must have quite unusual at that time.

It was a total shock. I remember my first day of school, putting on a school uniform, which included white gloves at that time. They rubbed Marmite in my hair – that was my welcome to Wellington! But moving from a blue-collar suburb in Connecticut – this kind of drab and cultureless place where I always got beat up at school and there was no larger world – Wellington seemed like a cosmopolitan paradise.

Why did your parents move here?

Well, the New Zealand Government had just started the Assisted Passage scheme, and my parents were having a hard time with uncovered medical expenses for my sister. And they’d always dreamed of New Zealand as a kind of social-democratic paradise. So they applied, and they were accepted. They emigrated when they were already in their 40s, which was a very brave thing, because at that time there was no going back. Plane tickets were very expensive, the exchange rate was unfavorable – they moved halfway round the world, sight unseen, and were there for good. And New Zealand in the 1970s was so remote and insular! Magazines arrived by ship from overseas, so you read them two or three months after the fact. There was only one TV station, and it shut down at 10 after “God Save The Queen”. The pubs shut at six. In a way, even though there’s a two-decade age difference between Sylvere and me, it was as if we were the same generation, because New Zealand was about that far behind the rest of the world!

And yet I’ve heard you say in another interview that moving to New Zealand saved your life. How so?

Absolutely. For a start, I would never have gone to college if we’d stayed in the US. I’d already more or less stopped attending school – my goal was just to take drugs and live in the park. School in New Zealand was a lot more interesting. The books we read in the 6th form, people don’t read in the US until graduate school unless they’ve attended elite private schools.

What kinds of books?

Just entire books, rather than textbooks. James Joyce, Eric Hobsbawn, Eveleyn Waugh…

I really loved the descriptions of Wellington in the 70s in I Love Dick: the parties at the BLERTA house, the larger-than-life public figures on the street like Ruffo the schizophrenic artist. When I read them, I had that experience of a nostalgia for a time that I never lived through, which you described looking at art installations of New York in the 1950s. Is that false nostalgia meaningful?

Are you talking about that feeling everybody has of having missed the best thing?

Yes, I think so.

No matter where you look back from, it’s always as if you’ve missed the best thing. We have to be careful, because we’re living right now the best thing that other people are going to look back on! I read a wonderful book recently by the artist Molly Crabapple, called Drawing Blood. She writes about her friends in New York in the early aughts, and she makes it seem like that time was the best thing. It’s a question that really interests me, and I looked at it in my book Where Art Belongs, that feeling people have about the last avant-garde. I wrote a history of a defunct alternative gallery, Tiny Creatures, who from scratch, and with very few art world connections, created their own ‘best thing’. For a while, Tiny Creatures in LA’s Echo Park felt like the centre of the world. The Zurich dadaists did the same thing in the 1910s, hiding out in Zurich to evade the draft in World War One, with the Cabaret Voltaire. What’s really amazing is when any group of artists work together with that intensity and seriousness they can make that place, wherever they are, the centre of the world. Somehow that always ends up radiating out.

How did you come to be a journalist for the Sunday Times and the Evening Post so young? I think you were still a teenager when you started working there.

Well, at that time, the Wellington Publishing Company offered a scholarship to Victoria students, that came with a job for a year. So in my second year at university, I won the scholarship, and I got a little bit of money and a job for a year. I started right away as a feature writer on the Sunday Times, which was fantastic! I liked it so much that they let me work full time. And then I stayed. It was a dream job for a writer, and a job that doesn’t really exist anymore. To be a journalist now is like wanting to be an artist or writer – there’s hardly a viable way to support yourself from the proceeds. But journalism is tremendously exciting for anyone with a sense of adventure, who wants to investigate, poke into things they’re curious about, and explore.

And yet after a few years you decided to move back to the States.

Right. When I was 21 I had a good job as TV critic for the Evening Post, a nice apartment, nice clothes, a nice car, and I looked at my life and thought “oh, this is the life I’ll be living when I’m 41”! When really, I wanted to be an artist. I couldn’t quite give that all up and go live in a Wellington squat, so like everyone else, I went overseas. First to London, which didn’t work out. And then to New York, since I still had a US passport. And there I stayed.

And what was that like, that transition back from Wellington, which saw itself as this cosmopolitan place but really wasn’t, to a truly cosmopolitan city with a thriving art scene in New York?

It was really terrifying. In Wellington there used to be this great Friday night ritual of drinking and shopping – everyone walking around totally bombed. I knew right away in New York, “you can’t do this here!” It took a long time to figure out how the system works, and how friendships and art networks are all so tied into where you attended college. I hadn’t gone to college with any of these people. There’s a truism that says that if you’re coming from an outsider place, it’s always going to take you ten years longer to get established, and if you’re a woman, you add another ten years to that. I think I’m a really good example. When I went to New York I was an avid spectator of all kinds of art and culture, but very much from an outsider place. I spent a lot of time alone, going to art shows and readings and movies. Finally I met the poet Jeff Wright when we were both office temping, and he introduced me to the St. Mark’s Poetry Project, that became my first social network. Even though I wasn’t a poet.

So you became first an artist, and a filmmaker, before you were a writer.

It was a pretty jagged path! I remember when I was a student in Wellington at Victoria. I was very shy, like everybody is at that age, and I was in a writing class, and I asked the question “how do you know what to write about?” And the teacher said “if you have to ask that question, you’re not a writer at all”. That put me off for about 20 years. Although really, I think it’s the only question. First I tried being an actress, but it was suggested that maybe I was too analytical to be an actress. So I tried being a director, and then in the 80s, I started making experimental films. I made about eight of them, and finally the feature film that I made in New Zealand, Gravity & Grace, that was finished in 1996. Throughout that time, I was hardly writing. But when Gravity & Grace crashed and burned as a commercial proposition, I started writing the letters to Dick. And writing those letters opened a door. It all came back: the intense focus of the reporter’s room, where you have only two hours to write 600 or 800 words on a deadline. No time for the anguish of the blank page! You just sit down and do it. So that’s what I started to do.

As I was preparing for this interview I was thinking about something you wrote in I Love Dick. You said the sheer fact of women talking and being paradoxical and self-destructive in public was the most revolutionary thing in the world. Then you said “I could be 20 years too late but epiphanies don’t always synchronize with style.” Given the surge in popularity of I Love Dick recently, do you think you were actually 20 years too early?

I mean, I wouldn’t say 20 years too early because plenty of other people were saying the same thing at the time, and had said it decades or maybe even centuries before. It seems less necessary now, because there’s been such a cultural shift in since the book was published. Women have become so much more present in the culture, to the point where we almost have parity.

You think so?

Yes, almost. Relatively. The culture has changed in so many ways. Hedi El Kholti, the managing editor of Semiotext(e), made the decision to republish the book in 2006 in a classic edition. And when it came out then, it was as if it were being published for the first time. It was picked up by another generation of readers and writers, and it fell right into that moment when a lot of really brilliant younger writers were writing blogs. In a sense, blogs are the same as zines, but they can travel a lot further and have a much wider reach. So there was already this incredible, young, female zine movement in the mid aughts, and the book fell right into that. People like Emily Gould, Ariana Reines, Jackie Wang, and Kate Zambreno hadn’t yet published their first books, but their blogs were very well followed, and when they picked up on I Love Dick, its audience metastasised. The audience grew very quickly, in a much different way than it could have in 1997. Some of the sentiments expressed in the book, particularly pertaining to gender, spoke to things that these writers were dealing with in their own work. So the book entered a dialogue with another generation, and that gave it a new life.

Has it worked out the way you’d hoped for women artists and writers? You say that there’s almost parity now, but do you think that women who are being themselves in public, and using their interior lives to make art are being fully understood and recognised for that work now, better than those you describe in the book who were doing it in the 1970s?

Well, it’s a good question. When I wrote the book, I was aware that women doing that kind of work – the second wave feminists – hadn’t been sufficiently recognized. Thankfully, that’s changed – there have been dozens of museum shows correcting that misperception. When the Museum of Contemporary Art showed Carl Andre’s work in Los Angeles, dozens of women showed up to represent Ana Mendieta. I was curious, and angry, about the lack of recognition of that generation women as artists – if they weren’t ridiculed, they were lumped together as ‘feminist artists’ – and many of them had just disappeared. Shulamith Firestone got it when she renounced the opportunity to be a ‘professional feminist.’ These women lived their lives and did their work at great personal cost. And their vision of feminism went way beyond gender parity – it was a re-visioning of the world.

Still, it’s not exactly as if I was on a feminist crusade when I wrote the book. When I began writing the book, my only goal was to sleep with Dick! And within the course of the book, that hope was realised, but like a lot of hopes, it wasn’t necessarily what it was cracked up to be! I wanted to understand why I wanted to sleep with Dick, and at the same time, I was trying to understand things about rural poverty, schizophrenia, the Guatemalan Civil wars, cultural isolation. You could say that that the gender question has played out quite well. Have all these things been resolved since 1997? Not so much.

What’s it been like, having your earlier novels reissued and revisiting the content like this in interviews and festival appearances and so on, when you finished working on them and thinking about the ideas such a long time ago?

Well, I can’t complain! You write a book because you want people to read it, and if people are reading it 20 years later, what more could you ask? I’m very happy that they’re reading it, and I don’t mind re-engaging with the questions raised in the book, but at the same time, I don’t want to get stuck there. I’ve moved on to other things – I just finished a biography of Kathy Acker that will be published in August. But this June, Torpor, the third novel in the I Love Dick trilogy, will be published by Profile Books in the UK, and I’m thrilled about that. Torpor is like the prequel to I Love Dick. When I started writing I Love Dick, I knew that it would be a trilogy. There were just too many questions to cover in one book. And the big, floating question behind I Love Dick is, what could possibly make a married couple collaborate on love letters to a third person? What is it with this couple? And in Torpor, the Chris and Sylvere characters become Sylvie and Jerome and it goes deep into the backstory of both of those characters.

I’ve just been reading Torpor, and really enjoying it.

Oh, that’s good! It’s more personal than I Love Dick, even though paradoxically, it’s written in the third person. People always talk about I Love Dick being so revealing and confessional, but it never seemed that personal to me. I mean, it’s so incredibly cliché! It’s so stereotypical that it could be anyone. Torpor is much more particular to the people. It examines historical trauma, both in Jerome’s past as a child survivor of the holocaust, and in the eastern Europe of the early 1990s that they’re traveling through – the devastation of the IMF’s ‘shock therapy’ in countries like Romania, where they are ridiculously, futilely, trying to adopt an orphan. The book is also a comedy, but a much darker kind. And in order to write that kind of dark comedy, I had to reveal a lot more about the two characters.

Yes. And actually I want to ask you about the decision to write about a real relationship, albeit fictionalised. What are the moral considerations in deciding what to share about somebody else’s story?

Well, there were two different cases. In I Love Dick, Dick’s surname is never revealed and all the identifying details about him were changed. Only later, when Dick Hebdige outed himself as the model in order to denounce the book, did his name appear. Still, I was careful never to write anything about the Dick character that Dick Hebdige hadn’t already publicly revealed about himself, in his interviews and writings.

Many women have been written about by male writers, probably without permission.

Yeah, you’re right. And writing always originates from real life, no matter how much it’s transposed.

The question ‘who gets to speak, and why?’ – do you still see that as the only question?

It’s more urgent than ever. The culture gap is wider than ever, and who gets to speak are the people who’ve been to all the right schools, who have grown up in culturally-informed families, who have social connections, etcetera, etcetera.

Finally I want to ask about Katherine Mansfield, because I loved the passages in I Love Dick about her and the connection you found to her work. A fantastic graphic novel was published last year by a New Zealander called Sarah Laing, called Mansfield and Me, where she set her own writing experience alongside Katherine Mansfield’s. It sort of seems like Mansfield has become the patron saint of New Zealand women writers, so many look to her to situate their work and look for connections between themselves and her.

Well yes, and surely Janet Frame as well. Absolutely. I think all writers do that. There are certain writers who make you become a writer. There’s a kinship with that other writer. It’s a really important connection. You read this person’s work and it changes your life in some fundamental way, and it opens something up, it opens a door, and you become a writer yourself.

Chris Kraus will appear at the Auckland Writers Festival in a solo session chaired by Australian hack Kevin Rabalais on Saturday, May 20, at 3pm; with Bill Manhire and other writers, each giving a 10-minute reading, on Sunday, May 21, at 10.30am; and she delivers a lecture on art practice later that day at 1.3opm. She will also be talking in Wellington, at the City Gallery, on Monday May 22, 6pm.

Her celebrated novel I Love Dick is available at Unity Books.