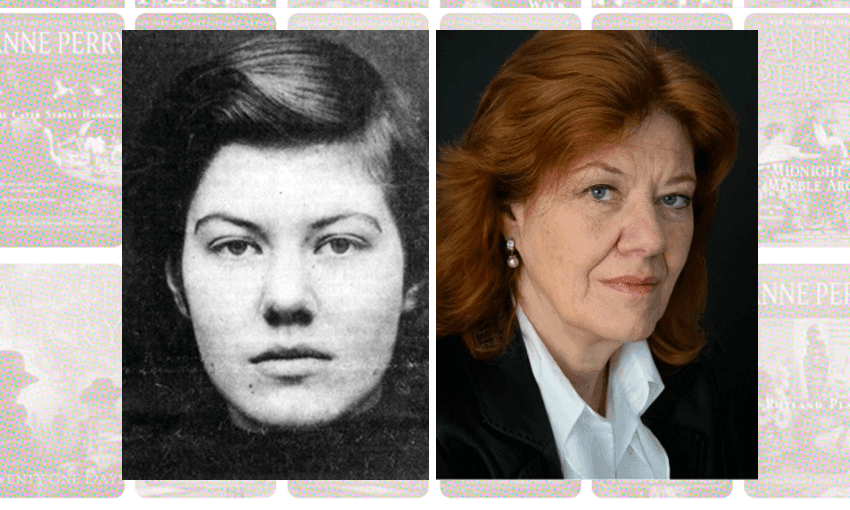

Crime novelist Anne Perry’s literary aspirations began in Christchurch in the 1950s. Back then she was Juliet Hulme and she and her best friend Pauline Parker dreamed of selling novels in America – before they were convicted of murder.

Earlier this week it was announced that Anne Perry had died aged 84. The personal biography section on Perry’s website outlines chronic illness as a child, her lack of schooling as a result, and her passion for writing, particularly crime novels: “I found that I was totally absorbed by what happens to people under pressure of investigation, how old relationships and trusts are eroded, and new ones formed.” There is no mention of the murder conviction that has dogged Perry’s literary persona since Peter Jackson released the film Heavenly Creatures in 1994, coinciding with the outing of Perry’s former identity: Juliet Hulme, teenage killer in Christchurch, New Zealand.

On 22 June 1954 Juliet Hulme co-murdered, with closest friend Pauline Parker, Honora Mary Parker, Pauline’s mother. In this (short, engrossing) interview with Ian Rankin, Perry says “my parents were separating, my father had lost his job, and we were about to leave the country. And I felt I had no time to find a better solution. She [Pauline] told me that if I left she would take her own life and I believed her.”

The matricide case was extraordinary for the time. It was the 1950s, Christchurch, and Hulme was from a well-off family. As minors, neither Hulme, who was 15, nor Parker, 16, could speak at the trial, though Pauline Parker’s diary was aired as evidence of premeditated murder. The diary included such choice paragraphs as: “We discussed our plans for moidering mother and made them a little clearer. Peculiarly enough I have no qualms of conscience (or is it peculiar we are so mad?)”. And (written the day before the murder): “Deborah [her nickname for Hulme] rang and we decided to use a brick in a stocking rather than a sandbag. We discussed the moider fully. I feel very keyed up as if I was planning a surprise party. So the next time I write in the diary mother will be dead. How odd, yet how pleasing.”

After being found guilty, Perry served five years at Mt Eden women’s prison, which she later (in this 2003 article) said was “the best thing that could have happened”. “It was there that I went down on my knees and repented.”

Upon release in 1959 Hulme changed her identity to Anne Perry, moved to Scotland, became a Mormon (Parker became a devout Catholic), and built a career as a crime novelist that resulted in more than 25 million books sold. When Peter Jackson released a fictionalised version of the case in the film Heavenly Creatures – described by Jean Sergent, in this review of the documentary Anne Perry: Interiors, as “frankly stunning […] a film which awakened the bisexuality of an entire generation of New Zealand women, or at least as far as me and all my bi goth mates are concerned” – Anne Perry’s quiet, devout, literary life imploded: “Everything I had worked to achieve as a decent member of society was threatened. And once again my life was being interpreted by someone else. It had happened in court when, as a minor, I wasn’t allowed to speak and I heard all these lies being told. And now there was a film, but nobody had bothered to talk to me. I knew nothing about it until the day before release. All I could think of was that my life would fall apart and that it might kill my mother.” (The Guardian, 2003).

The film, which starred Kate Winslet (Hulme) and Melanie Lynskey (Parker) caused a fervent resurgence of interest in the case, particularly in the relationship between Hulme and Parker which, in the film, is portrayed as a lesbian one. Perry always maintained that while it was an intense friendship, they weren’t lovers. It was in court that the lesbian narrative began, with the Crown arguing that they had become lovers in the time leading up to the murder.

It’s fascinating to read back over reports from the case which was tried by an all-male jury, a fact that might confound us today. Some of the language used by the Crown, the defence, and by the judge, was at times loaded and bordered on outright misogyny and homophobia. Crown prosecutor Alan Brown said the murder was a “callously planned and premeditated murder committed by two highly intelligent but dirty-minded girls”. The Star-Sun newspaper recounted Justice Adams’ address to the jury. He colourfully outlines the facts of the case as well as the circumstances leading to the murder: “At Dr Hulme’s place they wandered about together, keeping very much to themselves, scribbled in exercise books effusions which they called novels, spent a good deal of time in each other’s beds, and made plans for their future life together.”

And this from psychiatrist Reginald Medlicott who gave evidence for the defence: “There is evidence that they had baths together and had frequent talks on sexual matters. That is not a healthy relationship in itself, but more important, it prevents the development of adult sexual relationships. I don’t mean by that physical relationships, but attachment to people of the opposite sex. Homosexuality is frequently related to paranoia. When I first saw the two girls I knew that they were trying to prove themselves insane.”

In 2007, when fellow writer Ian Rankin asked Perry, “Do you find a certain irony in that you now make a living as a crime writer, having had your background?” Perry replied, “Really what I want to do is write a novel and a crime is a good peg to hang it on.”

Looking back at Juliet Hulme’s youthful literary aspirations (the “effusions”, as the judge called them), teamed with early, catastrophic experiences (the murder, but also her periods of hospitalisation for tuberculosis which included experimental mood-enhancing drug therapy; as well as her domestic upheaval), it is hard not to see Anne Perry’s literary success as triumphant, if not beguilingly complex.

In 2003 Perry told a Guardian reporter that, in her writing,”It is vital for me to go on exploring moral matters […] I wanted to explore what people will do when faced with experiences and inner conflicts that test them to the limit.”

Perry’s biographer, Joanne Drayton, said in 2012: “I look at Anne Perry and think, she had this devastating, terrible, utterly shocking start to life, and she’s pulled off something I would say pretty close to miraculous.”