We conclude our week-long series on the new memoir by former Green MP Holly Walker with a review by another ex-MP – Deborah Coddington.

Who would have thought Holly Walker, mother and Green MP from 2011 to 2014, was a victim of violent abuse while she was in Parliament? Her face was so badly bruised she lied to her colleagues that she’d had wisdom teeth extracted. Walker then told her family, who knew those teeth went years earlier, she’d accidentally hit herself manhandling the baby seat out of the car. These excuses fell apart when a colleague who’d swallowed the tooth story overheard her relating the car seat story. The unnamed colleague was suspicious, but never followed up what was obviously a woman in deep trouble, covering up private pain. Walker spills all this and more in her searingly honest memoir, The Whole Intimate Mess.

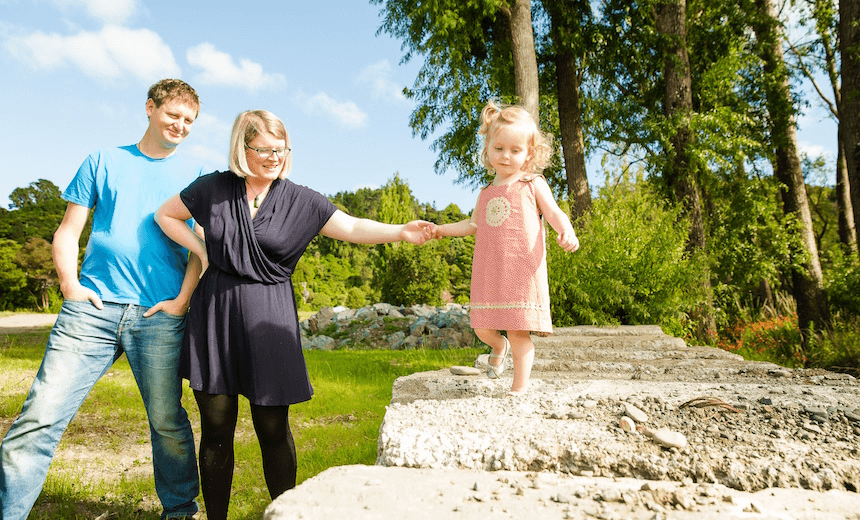

But Walker wasn’t abused by her husband Dave. Mired in anxiety and post-natal depression with first baby, Esther, and so overwhelmed with her chaotic Parliamentary duties, Walker’s marriage turned to crap. Behind the closed doors of their Hutt home, vicious arguments erupted over ridiculously petty issues, such as who should load printer software into her laptop, who should tend the new baby. To bring these fights to an end, Walker resorted to bashing herself on her head, over and over, until she was injured.

The Whole Intimate Mess is the short title, taken from a quote by New Zealand painter Jacqueline Fahey: “Oh, stuff it, I’m sick of this, let’s take all my clothes off, put it all out there in a whirlwind, the whole intimate mess, so there is nothing left…If I am honest about what’s going on in my life then it’s got to be relevant to other people’s lives.”

Motherhood, Politics and Women’s Writing is the long title, though a comma is needed between politics and women’s writing because they are not connected in Walker’s story. Women’s writing is relevant because she left Parliament so broken she chose to read books written only by women: “like choosing to buy free-range eggs” she writes.

This is a depressing, sad book. An intimate mess indeed. But that doesn’t make it not worthwhile. Walker deserves credit for stripping herself bare on these pages. I suspect the writing was cathartic; though as I read I kept wondering why nobody offered an elixir when this woman was clearly in need of professional help.

It gets off to an eye-rolling start which initially made me suspect yet another cliché: Walker breaks her silence on depression/suicide attempt/what-have-you. This meme is doing the rounds with sportspeople, minor celebs, and columnists. So why should her story be any different from the hundreds of other former parliamentarians? Just because she left to care for her family, does she think the constitution should change to make the House family friendly?

How, exactly?

As I wrote this review the Green Party confirmed its list for this year’s election with three new young women in the top 12 – Hayley Holt, Chlöe Swarbrick, and Golriz Ghahrahman. How happy they looked, eager to take their seats in the house, throw the first questions at the Government, stride into select committee. Just like Walker was in 2011; full of ideas to change the world and, in her words, become “infamous” as that Green MP in the little green car.

Like Walker, their lives will never again be the same: if they make it to parliament, politics will define them. Some may become stars, some may last one term.

It will be tougher than they can possibly imagine, as everyone – from so-called friends, to the Opposition (behind them), to the media – does their best to lead them into pratfalls. As Tom Scott once paraphrased, “Those whom the gods wish to destroy, first they make famous.”

If these women only do one thing, they should read Walker’s book.

Because her self-indulgent first chapter has its purpose. She portrays herself superbly as a brattish clever clogs when she decided to stand for Parliament. Three times she crows she was an Oxford Rhodes Scholar; “we are insufferable”, she writes, and she realises what a pseud she must have seemed as a candidate trotting out the clichéd life story of going from rags to riches when she can remember privilege – a nice villa, warmth, comfort and a great education. But she admits she was “headstrong, opinionated, an over-achiever, success came easily” and “a feminist”.

Girls like her were told they could do anything, have everything. Furthermore, she didn’t accept what Marilyn Waring said about eliminating the first person. She wanted to improve the world, sure, but she wanted celebrity and approval. She was proud of being a “trendy lefty”. What could possibly go wrong?

By the end of chapter two, when Walker’s admitted she just wanted to be liked, I do like this author for the sheer guts it took to take a good hard look at herself. But I haven’t got to the best part yet.

She didn’t hit the ground running when she got to Parliament. It’s not mentioned if she got much help or advice from her Green Party colleagues, apart from when she was near to tears and Catherine Delahunty agreed to speak for her on a Bill. She doesn’t write ill of her fellow MPs, but neither does she praise them.

Walker was terrified when she went into the debating chamber. She went into politics to use her voice, she writes, but from her maiden speech, when she choked up at trying to talk about her nana, she found “for the first time…my voice failing me. It was to be the first of many. The first time I stood up to ask a Minister an oral question my heart was beating so fast I thought I would forget to breathe.”

It’s astounding that this became a big issue for Walker. Why was she not reassured, I wondered. This panic is normal for any new MP – you learn from your mistakes.

An aside: in 2002 I was a newbie upstart, thought-I-knew-everything backbencher MP in the Act Party. As I skipped gaily to my seat for the first time, wise old tuskers as experienced as Winston Peters and Richard Prebble warned about how intimidating, lonely and unforgiving the debating chamber could be. Pffft, what do they know? More fool me. It’s bloody terrifying. I was too scared to pick up my glass of water, my hands were shaking so much. It’s fear of being mocked, laughed at, saying the question incorrectly (there is a strict protocol), jeered – and then you have to concentrate on the answer and ask your supplementary. But after a few days of this, as Prebble told me, you just have to stare down everyone and think, well Eff You, and focus on the job in hand.

But Walker took this as failure, and so began her downhill spiral.

She lost her way to the Select Committee room and was late, then was teased, and became so nervous about the agenda and speaking order she was too afraid to talk at all.

To her surprise there was more to being an MP than simply “asking questions in the House and going on the radio”. She advocated a strong housing policy, “but what did I know about how plumbers, gasfitters and drainlayers should be regulated? I was Arts, Culture and Heritage spokesperson because I loved books and writing, but what did I know about the standard to which heritage buildings should be earthquake strengthened?”

On and cumulatively on her woes piled up, which raises two questions: as a former Rhodes Scholar who from 2009 worked in Parliament for the Greens, why didn’t Walker have the nous to figure this out prior to standing? But more important, against this background of not coping with everyday parliamentary work, why did she decide to add to her stress by deciding to have a baby?

Walker admits she saw it as a chance to show women could have it all. Isn’t it about time someone, somewhere, blazed across the sky: if you choose to do one thing you are, ipso facto, forgoing something else?

Walker crashed.

I left Parliament 12 years ago and things may have changed but I can’t imagine the horrors of handling Parliamentary work and a new baby. It was bad enough coping with the tantrums, toy tossing, dummy spitting, food throwing and wailing for a bottle in Question Time.

Former National MP Katherine Rich (ironically the only MP Walker unconditionally praises for her support) had two babies while she was an MP and she lived in Dunedin, not 30 minutes away in the Hutt like Walker. Rich never complained at the time but 15 years on she can’t bear to recall the stress. She breastfed her babies in the House (not at Question Time) and had a very supportive husband, Andrew, who moved to Wellington when the children were babies and gave up his work to look after the kids.

Walker’s domestic scene was anything but bliss. For example, the first time she returned to Parliament after three months maternity leave, she asked Dave to bring the baby in for a lunch-time breast feed. She writes he couldn’t promise anything: “he didn’t know how the day would pan out.” She reacted by smacking herself repeatedly on the top of the head before collapsing in a sobbing heap. This went on for months.

Walker’s husband suffers from a rare and mild form of muscular dystrophy which means he can’t lift, is in constant pain, and suffers from depression. Yet another handicap, which to be fair, Walker knew about when they married, but it curtailed his caring for the baby. They hired a nanny but she says it was too late. What seems strange is she doesn’t mention help from extended family, good friends, or colleagues.

Instead she considered herself a failure and decided to chuck in her political career.

The success or otherwise of a political career should not be judged on its duration. There are MPs still in Parliament who should have departed years ago. The mere fact she’s written this book shows some good came from Walker’s political term – it’s a stark warning not to embark on motherhood while you’re an MP unless you have a totally supportive, committed and loving partner plus plenty of extra arms into which baby can be passed.

Walker wants more women to be able to enter Parliament and care for their families without going through the anxiety and stress she suffered. There needs to be greater flexibility, she argues. She was granted 16 weeks paid parental leave (on full MP salary). When she returned she was allowed home at 6pm (unlike Katherine Rich who had to stay until 10pm) and her colleagues took over her portfolios. Walker was further – very generously – allocated other Green MPs’ evening leave when hers ran out. So it wasn’t as if she didn’t already have a lot of flexibility.

She doesn’t articulate where, exactly, she would like to see further changes made – a frustrating omission. She finds fault without suggesting how the House could be improved. A little more showing, and less telling, would have improved this book. For example she writes of “the constraints of the parliamentary environment” but to those who’ve never set foot in the place, this is meaningless.

But this is a courageous and truthful book. I quibble with the publisher’s tag that Walker is a “great New Zealand writer”, but thankfully she writes without literary pretensions, just telling her story clearly so nothing gets between the author and her readers. At one stage the narrative is a bit out of kilter – for instance we first meet Esther when she is eight months old and happily cooing, then she is being born, next she’s nine months old screaming in terror while her parents fight and Walker smashes herself in the head and crawls along the hallway. Then on the next page Esther is five months old.

There’s one incident Walker remembers incorrectly – when former Australian Prime Minister Julia Gillard came to Lower Hutt. Perhaps Walker’s memory was clouded by trauma. She felt uncomfortable, she writes, from the moment she walked into the auditorium – because MPs Trevor Mallard and Chris Hipkins were there, along with new MP Chris Bishop whom she knew from university days. After Gillard’s “talk”, Walker told Gillard in front of the 500-plus audience she’d stepped down from politics for family reasons and asked what needed to be done to accommodate more parents in Parliament. Then she felt so ashamed of herself for admitting failure “next to my former peers” she rushed home and “pulled the duvet over my head”.

I was hosting Gillard that night. It wasn’t a “talk”, she was “In Conversation” with me, and I chose who asked the questions, including picking Holly Walker’s upraised hand. She didn’t make a fool of herself; it was a valid question, particularly because many in the audience were senior pupils of Chilton St James School, possibly young women considering how they might combine a career with a family.

This is another example of how Walker is far too tough with herself, so perhaps she’s just too hard on everything, including Parliament. Undoubtedly changes could be made to the system in the behemoth, but raising a baby is one of the most important things a mum or dad can do. Should it be slotted between points of order, supplementary questions, constituency meetings, select committees? Certainly not when a woman ends up badly mentally and physically hurt, no matter who is inflicting the abuse.

Perhaps I’m just old-fashioned. I had my first child five days after I turned 22, 42 years ago, and I loved raising babies. But at the same time I watched with envy as my journalism colleagues soared up the career ladder while I felt abandoned in Wairarapa teaching a little one to talk, garden and cook playdough. But when my four children were at school I could claw my way back up to the top in journalism, full time, then look at those same colleagues, now in their late 30s, early 40s, struggle with IVF, difficult pregnancies and exhaustion as they juggled early childcare and jobs.

My point is you actually can have everything; but maybe not at the same time.

More about Holly Walker and women in Parliament this week on The Spinoff Review of Books:

Monday: An excerpt from Holly Walker’s memoir The Whole Intimate Mess

Tuesday: Green Party candidate Chlöe Swarbrick in conversation with Holly Walker

Wednesday: Tessa Duder on writing Alex, the YA novel Walker credits as a formative influence

The Whole Intimate Mess by Holly Walker (Bridget Williams Books, $14.99) is available at Unity Books.