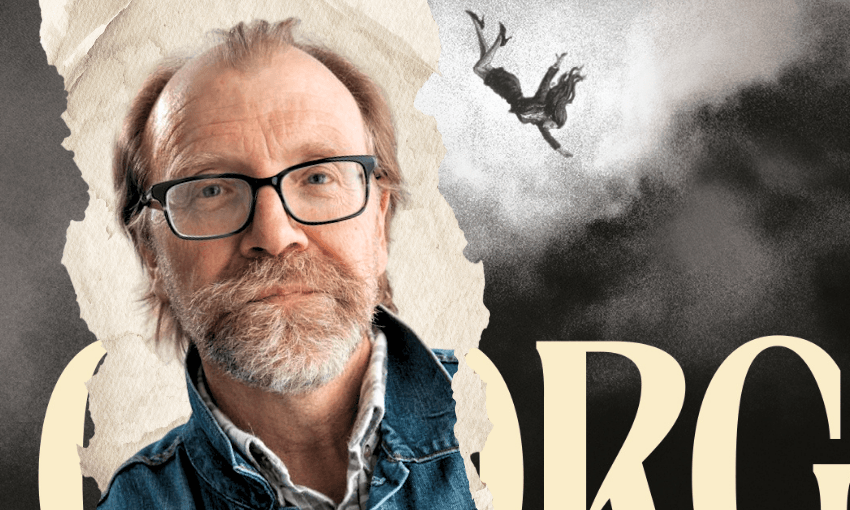

Poet and writer Ben Brown (Ngāti Mahuta, Ngāti Koroki, Ngāti Paoa) reviews the author’s new memoir, From the Centre.

“Sometimes when I am asked why I became a writer, I say that it was because of the availability of raw materials when we were children. I think there’s some truth in it.”

Paper is in plentiful supply when dad works at a stationery manufacturer. He’s handy with a knife as well and sharpens pencils carefully.

“At the other end of the pencil, he would slice away a shaving and write my name there.’”

An intimate memory. Cherished in the detail. The father who read to her from a single book of fairytales, covered her exercise books with the measured, cut and glued ends of wallpaper rolls, waiting to go to war with the Māori Battalion. The “raw materials” extending far beyond the basic tools of the trade to the keen observations of an astute young Māori mind sensitive to a growing awareness of “being different”.

“I found that being different meant that I could be blamed…”

Being different. Being brown. Being Māori.

My sense of Patricia Grace is one of quietly implacable resolve. She is that particular type of Māori woman who will – who will – follow through to the end whatever mahi she has set for herself, on her terms. It’s more than a mindset, this resolute spirit. It is her very being. It is the muka in the harakeke.

In her new memoir From the Centre, Grace weighs her words carefully, wasting nothing, expressing the gravity, joy or disappointment of a moment in time with a clarity of language and a deep understanding that life is full of complexity and contradiction.

“The affection I held for this grandfather when I was young lessened as I grew and came to realise his deep prejudices. This came to a head for me when I overheard him talking to his brother, making derogatory remarks about my father, who had always treated him with kindness and respect. I managed to do likewise, treat him with some respect…”

So it is that a young Māori girl growing up in post-war, post-colonial Aotearoa begins to understand.

Patricia Grace is kaiwhakahaere. She is one of our great navigators. When I say “our”, I mean all of us who choose to try and make our way beneath the long white cloud. The life she charts in her journey “from the centre” is Aotearoa New Zealand revealing itself before her and around her. Grace renders her kōrero from the purviews of deep observation and personal connection, producing an anchor stone of resolve to keep us pointed properly home, allowing discomfort sometimes in our travels – discomfort that tells us something about ourselves.

Memoir serves the historical record by offering a uniquely personal perspective, an individual account of the times. In this instance, a Māori woman of Ngāti Toa Rangatira descent, a teacher, a writer – so a tōhunga as well – reflects upon a remarkable career that saw her begin as a singular entity, a voice in her own wilderness determined to present her own record on the simple yet profoundly powerful idea in mid-20th century New Zealand: that a Māori woman has real and relevant stories to tell.

Grace was born in Newtown, Wellington, in 1937, the same year as my own Māori mother. She notes of her school years: “I was continuously having to prove myself. In some ways this was good for me. It made me strive, always needing to have high marks, excellent reports, neat books and handwriting.”

She would come to understand the source of her frustration was not an overbearing yet ultimately altruistic education system striving for universal excellence, but rather the consistently low expectations directed at Māori students generally. Fortunately for both herself and the New Zealand literature canon, as Grace understates, “These were matters I just learned to deal with.”

As the writer then, she begins in her living room by a window in the sun. She begins with Sargeson and the realisation that here is valid. She begins with Weet Bix and the Cremota Man and Knights Castile for a King in a Castle. She begins with mana kupu, matatuhituhi defining the pūriri, the tui, the kereru and the whenua, her beloved Hongoeka.

Ah yes, when a Māori writes about te whenua, look out! That way there be monsters, or taniwha perhaps. Or is it more just a carefully enunciated revelation of deep down, what we all know to be so? Patricia Grace is unafraid to place herself at te pūtahi, the centre, the convergence of this conversation.

Around her and within her stirs a post-colonial narrative before the term or the terrain was even envisaged or defined. A Māori woman coming of age in the New Zild of the ’50s and ’60s, of keen observation and literate predisposition, must have felt compelled to evoke and elaborate upon this nation evolving around her.

Can you even begin to imagine the implication of a young MāorI woman driven to inform us of our foibles and quirks and our darker selves little more than a century after her people first were exposed to and then embraced the written word? We are fortunate that, in her writing, deft and measured commentary met an adamant and mature resolve to show us to ourselves. Sometimes we need teachers with a less abrasive tone to tell us what we should already know.

Grace writes, matter of factly: “I grew up amid two worlds, having close and frequent contact with each. These were two different and contrasting spheres that I inhabited, both full of life and vitality: my mother’s Pākehā family and my father’s Māori whānau.”

Regarding her novel Potiki, a story about a Māori community on the coast being threatened by developers, Grace explains: “When I started writing, what I was thinking about was writing about the ordinary everyday lives of people that I knew, and it (Potiki) has been described as a very political novel, but I didn’t think of it that way, because issues to do with land and language are things that Māori people live with every day so to me I was just writing about everyday things…”

Think Raglan Golf Course, Bastion Point and of course, her own cherished papa kainga, Hongoeka Bay. Think of hundreds of unknown places that should, as a matter of course, be known – to all of us, Pākehā and Māori alike.

But really, te whenua is not the heart of it at all. The land was there before us, it will be there when we are gone. He tāngata, he tāngata; it’s always about the people. In the rendering of character we observe the mana of humility, where the bigot and the bully are almost forgiven, but not quite. Ignorance, in the end, must simply be dealt with, with a sure and implacable spirit. While the loved are laid bare with their secrets intact, yet somehow, we know. Or so we are led to believe.

“Perhaps the time was right for a stocktake, time to get in touch with beginnings, a reminder of a time when I’d had an unshakeable self-confidence,” writes Grace after an encounter with an unwanted cup of tea and a wonderfully eccentric oracle of the tea leaves. If this book is the reminder, Grace remains unshakeable.

From the Centre: a writer’s life, by Patricia Grace (Penguin, $38) is available from Unity Books Auckland and Wellington.