Novelist, journalist, former missionary and now full immersion te reo Māori student, Shilo Kino has packed a whole lot into three decades. She speaks to Michelle Langstone.

Portraits by Edith Amituanai.

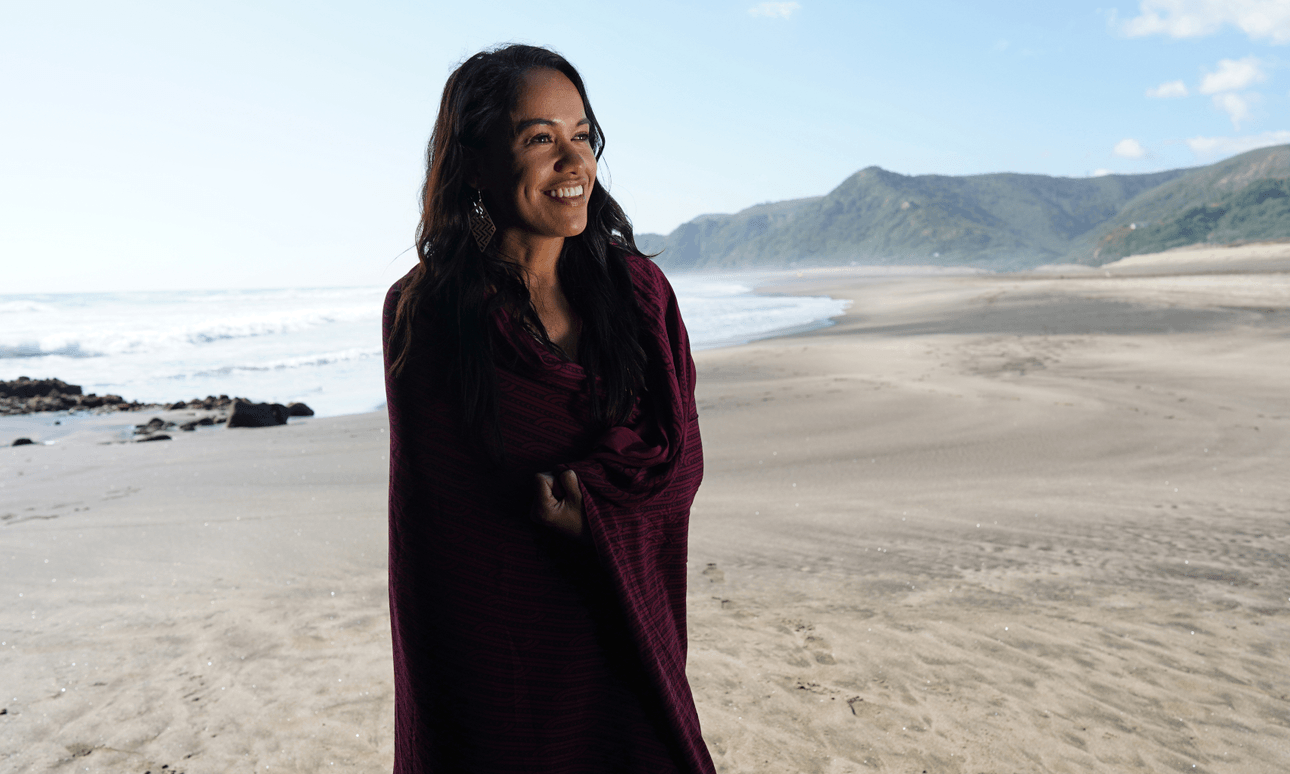

Shilo Kino sits on the black sand at Piha with her knees drawn up to her chest, hair falling across her shoulders, the smile wide on her face. She’s 31, but seems much younger. She’s packed a lot into her adult life – she’s been a missionary in Hong Kong, a journalist with the New Zealand Herald and then Marae TV, and her recent op-ed pieces for Newsroom and the Guardian about racism and Māori issues in Aotearoa have garnered a lot of attention. She’s also the author of the highly successful 2020 young adults’ novel The Pōrangi Boy. The book, about a teenage boy named Niko, who alongside his koro stands up against developers who want to build a prison in their town, went to reprint just eight weeks after it launched, and has appeared regularly on the Nielsen bestseller list for New Zealand titles. The novel is authentic, steeped in identity and activism, and speaking to Kino, it’s evident that writing it informed her own journey in reclaiming her Māori heritage, and finding her own voice. This year, with another book in development, she’s taking time away to further embrace her deepening connection to her Māoritanga; she’s enrolled in a full-time, full immersion te reo Māori course in Tāmaki Makaurau.

Kino’s CV reads like she has always been engaged with her culture, but she’s the first to admit she grew up disconnected from her Māori identity. Born in Whangārei, and Tainui on her dad’s side, Ngāpuhi on her mum’s, early life took her away from her immediate whānau: “My parents divorced when I was a baby. Mum left my dad and we moved to Waipu, where she met a pākehā man. I grew up in Waipu, which is the whitest town. We were pretty much the only Māori family. I look back now and it’s so funny, because I knew more about Scottish culture than my own culture, because Waipu celebrates Scottish heritage! I knew the names of the pioneers who came and settled in Waipu, and we celebrated them … but I knew nothing about my own culture.”

The Spinoff could not exist without the support of its members. Click here to keep The Spinoff ticking.

Kino laughs a lot when she talks about her upbringing – how her mum came in to teach the kids in her class to count to 10 in te reo, but that was the only part of her heritage that was shared in school, how this little Māori kid participated in the Highland games to mark the Scottish heritage of the town – but you can see deep sadness in her eyes even as she jokes around. She was lost to her own culture for a long time. As a child all she wanted was to be white, and her expression is pained when she tells me, “When I watched the news I always felt whakamā about being Māori. I just didn’t want to be Māori. I tried everything I could to not be Māori. I just wanted to be really smart because I thought Māori weren’t smart. Everything that I saw from a child’s perspective was that white people were the smartest. And I was smart – I was in the highest class and stuff, you know. But you can’t take away skin colour, so I was still Māori.”

There’s a sense that Kino has been lost more than a few times in her life. Certainly her childhood feels dislocated, uncomfortable. When she speaks about her journey to where she is now as a successful author and journalist, it feels as if she’s only just arriving in her own life. Adrift in her early 20s, she initially turned to religion in her search for meaning. “I think I just woke up one morning and I was like, ‘What is the purpose of life?’” She rolls her eyes, making fun of herself “What a deep question! I think I was hungover too, when I woke up. And that was such a common thing too, in your 20s, right? Drinking and partying and doing all that. And I just woke up one morning and was like – what is my purpose? What am I doing?” Kino found God, and ended up in the Church of the Latter-day Saints, spending a year in Hong Kong as a missionary. “Coming home knowing Mandarin but not knowing Māori … that to me was an eye-opener. It taught me a lot about the power of language, and it connected me to the Chinese people in such a strong way.”

Kino still retains her faith, but she never stopped wondering about her purpose. “I still don’t really know clearly, but I do know that I have been given gifts, and one of the gifts is storytelling. I know one of my purposes is to help the liberation of Māori through storytelling, whatever that looks like.” You can feel that intention in The Pōrangi Boy. Kino based the story on the Ngawha prison community protest in Northland. Kino was just a kid when the small town fought the construction of the Ngawha Prison, but she the story stayed with her: “As an adult I wanted to learn more about what actually happened with the prison. It kept coming into my head and I thought – man I need to do something about this.”

In Kino’s novel, brought simply and beautifully alive with a blend of te reo and English, Niko and his koro fight the Pākehā developers, and a prison that will go on to have serious impacts on the town and its people. Kino was editing her first draft when she was working for the New Zealand Herald in Tauranga, a time in her career she found frustrating and disheartening. “The people [at the Herald] aren’t racist, but the way they were framing Māori stories was contributing to a lot of racism. I was uncomfortable with the stories they were publishing about Māori.” Kino was reporting on Māori stories and remembers wading through the public submissions when the council made a move to gift some land back to the local iwi. When she tells me about it she becomes agitated: “It was really racist things like ‘Māori are responsible for burglaries’ and all of that. And it was ongoing – there was a councillor who said that he wanted to burn the treaty. That was going on at the same time that I was editing The Pōrangi Boy. It was initially going to be about a taniwha, but that completely changed from that to a protest, and to activism and why that’s important.”

Kino eventually quit her job at the Herald: “I was just following my gut. I knew I wasn’t going to stay there long term, but I just couldn’t handle it any more. I think it’s a common thing for a lot of Māori journalists working in mainstream media, especially if they’re alone, because you need that community support of other Māori journalists.” The move to Marae TV evidently brought relief. “Being able to tell Māori stories without having restrictions, or having to explain why something is a story, and being able to tell it in my way … I think that was what confirmed that I was in the right place.”

The Pōrangi Boy is also about standing up to bullies in your community. Parts of the book where Niko is harassed and physically threatened are incredibly raw; the young protagonist’s pain and whakamā is evident. I press Kino for details of her own experiences at school growing up, because the book is heavy with the weight of a very specific reality. She draws the wrap around her shoulders closer to her body, as if she’s suddenly cold. “I’ve never talked about this, but a lot of what happened in the book is based on my own experience. I was definitely bullied growing up. I was bullied for being Māori and I was bullied for being weird. I always felt different, like I didn’t belong anywhere.”

For Kino, writing Niko’s story was an opportunity to experience a courage she never knew as a kid. Living vicariously through Niko’s journey has also allowed her to reflect that she has in fact overcome the bullies in her own life: “I feel like I’ve had my own victory. It’s not like I gloat in my own achievements or anything like that, but for those that bullied me, I can see now that I’ve done so well in who I am, in my career and my life. But I wish I was as confident as Niko became in the end, when he realised that he was the tohunga. He became the person that he was meant to be and I think that’s kind of a beautiful analogy for all of us.”

The similarities to Kino’s life don’t end there. Niko’s friend Wai has a dad in prison in the story, and she disappears after school because the whānau are expecting a call from him inside. Kino’s dad, a former gang member, was also in prison when she was a young child, and she remembers those phone calls, and writing him letters. She smiles broadly when she speaks of him. The relationship with her dad sounds like one of deep love and respect — the pair live together in Te Atatu, and through her dad’s stories, Kino has grown to understand the true impact of colonisation on Māori: “My dad grew up in a really loving family. My grandparents passed away before I was born, but what I know about them, they were so lovely. So I tried to make this connection – how did my dad end up in the Mongrel Mob? When he was 15 he moved away from a whānau setting, right? To an Auckland setting, and that must have been in the 1980s. When you take away the Māori whānau support, and you are an outsider and confronted with racism and all those things, what do you do? You try to find a community who look like you and accept you for who you are. And he found it in a gang. He didn’t know his language and his culture, because his grandparents were beaten for the culture, so we can always tie it back to colonisation.” Kino has based much of the proud, courageous spirit of Koro on her dad. Her eyes get very bright when she tells me that; you can see how proud she is of him, and the things he has overcome.

Kino talks about colonisation a lot. As a writer and a journalist she is actively pursuing narratives that redirect the colonial lens that has been placed on Māori, leaving them to tell their own stories. She plays deftly with the frame of reference on perceived “Māori issues” in her debut novel; while Wai’s dad is away, and Niko’s mum unwell and struggling, these problems don’t occupy the foreground of the story, and that’s the way Kino wants it: “I think that’s the difference between when we tell our own stories versus when a non-Māori tells our stories. Yeah – Niko’s mother is on drugs and Wai’s dad is in prison. There’s a lot of poverty that’s in there. But it’s not the focus. The focus is on Niko and Koro, and the beautiful culture. All those other things are kind of happening in the background, and I think that’s true for Māori, right? We do have these issues but it’s not who we are.”

We talk for a while about representation in Māori in literature. It’s almost non-existent in YA fiction, though more present in adult novels. Perhaps inevitably, Alan Duff’s Once Were Warriors comes up. The novel garnered international attention when it became a huge film, but the association of violence with Māori culture has arguably left its mark. Kino is careful when she speaks: “I think for Alan Duff and for Once Were Warriors, the problem wasn’t Once Were Warriors specifically, the problem is that there was nothing to counterbalance the negativity. That movie and that book – I remember that growing up, that was like the only Māori story, the only Māori movie, right? For me I was teased all the time: ‘Oh, is your dad Jake the Muss?’ That only perpetrated the negative stereotypes, and that’s a problem with Māori storytelling – there’s not enough stories to be able to counterbalance. If there were more stories that wouldn’t be the only story.”

Kino chose to write a YA novel to speak to kids like her when she was growing up, kids who felt disconnected or ashamed of their culture. There was no representation for her in the books she came across in her frequent lunchtime visits to the school library; her favourite books were The Babysitters Club series. Now she’s writing the stories she so needed back then. “That’s why I get so passionate about being a journalist and trying to tell positive Māori stories, or writing a book that’s going to make a Māori child read it and feel proud to be Māori. I wanted to focus on children because I think our children are the most vulnerable and the most impressionable.” She pauses for a moment, to consider her words, and then grins “But then when I finished writing it I was like – actually it’s the adults that need to read it! It’s the parents! Children already know a lot of what’s going on in the story and they wouldn’t be surprised, but I think adults would.”

Kino has been surprised by the success of the book – already in its first reprint after being released in October, and making its way into schools across Aotearoa. She never expected it to do so well. When she received her first copy she put it straight into her desk drawer, spooked. “I was scared about writing it, because I had such a negative view of activism because of the way I’d grown up with the media. I feel like the media have weaponized activism. I was like, ‘Ooh, I don’t think this story will do well, because the front cover is a Māori boy, with land on his hoodie, and pōrangi is a Māori word, and pōrangi means crazy. I never ever imagined it would do as well as it has, but I think it’s a reflection of people becoming more hungry for indigenous stories.” Feedback has come from some surprising places: “The messages from grandmas have touched me the most. ‘I read this with my grandson, I’m not Māori but I love this so much, thank you. I was in tears I was so moved by the story.’”

Not content with resting on her success, Kino has a new YA novel in the works, loosely based around the Black Lives Matter protests in Aotearoa. She’s excited to be writing again, and like The Pōrangi Boy, her new book will focus on identity too. It’s the centre of everything in her life, and now she’s on a journey to get to the heart of her own. Full immersion in te reo is part of her personal reclamation, she tells me, hugging her knees in tight to her chest: “I think I’ve always felt that there’s something missing in my life, and I haven’t been able to explain logically what it is. Coming back into my culture I know is a big part, but it’s still not enough.” Kino says she’s done everything she can to try and learn the language over the years, but she got stuck somehow, the words never flowed, or met her unconsciously. Sensing the language might be the key, she’s finally ended up at school. “I feel like doing this course has been out of desperation, like I have no choice, almost. I feel like I’ve been pushed by my ancestors to do it.” Alongside her study, Kino is making a podcast called Back To Kura, tracing the journey to fluency with fellow student Astley Nathan. Kino doesn’t know what she’s looking for, but she’ll know it when she finds it. The result of this journey may mean the end of a job in journalism, or some other kind of new beginning. She has no idea where she’ll end up, but there is lightness in her when she tells me that her ancestors have a purpose for her. She laughs and tucks her hair behind her ears. “I just don’t know what it is yet! Or what will come out of the language …”

Shilo Kino is appearing in the 2021 Auckland Writers Festival’s Schools Programme