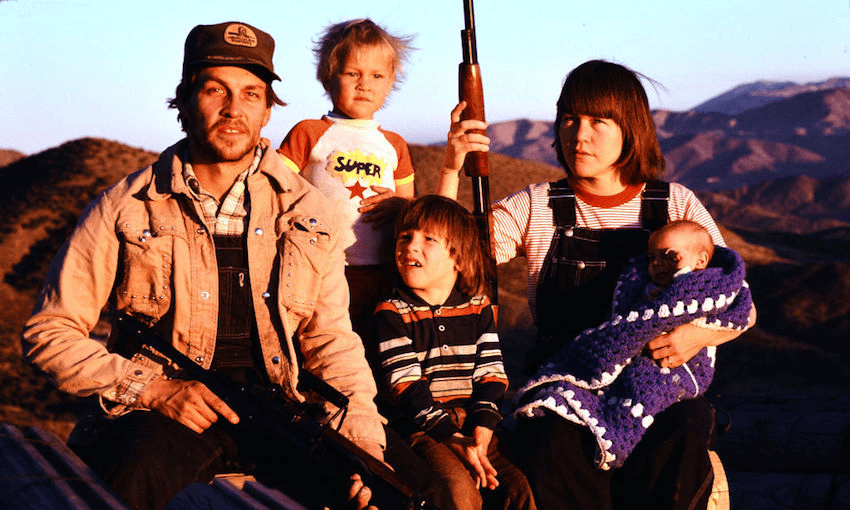

Broadcaster Kim Hill reviews the year’s most sensational memoir of family dysfunction, violence, apocalyptic visions, and survival.

Memoirs are by their nature spoilers. We know already that the author survived trials and hardship because here’s the book. And so many now: since the modern “misery-memoir” genre (happiness writes white, after all) was boosted in part by Frank McCourt’s blockbuster, Angela’s Ashes, the past couple of decades have been full of them, good, bad, or embellished to the point of fiction. Tara Westover’s Educated is a good one.

Her story is a kind of gasoline gothic, punctuated with tour de force descriptions of horrific accidents that should have culled her survivalist family, and all of them involved cars. On the way back to their Idaho home from Arizona, where the sun has jolted her father out of his depression, the car leaves the road and Tara’s mother suffers a serious brain injury. Another crash leaves Tara paralysed and in pain for weeks.

And then there’s the junkyard, where the family strips vehicles and salvages the petrol to see them through the coming Days of Abomination. Tara is trapped in a bin with an iron spike through her leg. Brother Luke’s legs are burnt when his petrol-soaked jeans are ignited by a cutting torch. Brother Shawn falls and sustains a serious head injury, but shortly thereafter is back in the junkyard working on the Shear, which chomps through iron and delivers repeated blows to his head with hunks of metal, an unavoidable occupational hazard. Another road accident leaves Shawn with his brain exposed through a hole in his head.

Finally, the father whose mania is responsible for all of this gets his comeuppance. Badly burned in a fuel tank explosion, the lower half of his face is liquefied, his mouth a lipless hole, his ears “so burned they’d fused to the syrupy tissue behind them… the first thing I saw was Mother grasping a butter knife which she was using to pry my father’s ears from his skull.” His recovery proves God’s power.

Almost all of these disasters get DIY health care, because Father has decreed that doctors and hospitals are an abomination to God, the work of the Illuminati.

Tara has to get away from that junkyard.

She manages to recreate the details of life in an Idaho valley cult without arousing the reader’s suspicion (how could she really remember all that? And good lord, can it be true?) because along with great descriptive powers, she includes an endearing series of notes about the sources of some of her accounts, allowing for others’ differing memories. Here she makes a crucial point: ”We are all of us more complicated than the roles we are assigned in the stories other people tell. This is especially true in families.”

Doubly endearing: as well as a gracious acceptance that her view is not the only view, it also leaves open the possibility that her father was a better man than some stories might suggest.

Nice of her. Cuts no ice. The best that can be said about her father is that he was mentally ill. She suspects bipolar disorder, as does her mother. His paranoia and hatred of The Establishment would have prevented diagnosis and treatment anyway. The cult, a break-away from the increasingly reasonable-seeming Mormons, is her family: seven children, her father the leader, her mother either a victim or a collaborator.

None of the children go to school or see a doctor. They grow up preparing for the day when the sun will darken and the moon drip as if with blood, and meanwhile, a lot of peaches need to be bottled and stored, the military-surplus rifles buried, and the bullet-making machine cranked up. The Feds are coming and will kill them as they have killed Randy Weaver.

Her father insists that her mother train as a midwife so that she can deliver the grandchildren when they come along. It’s unclear whom his sons and daughters will breed with…Meanwhile, they toil in the junkyard. But it’s possible to escape: Tara’s brother Tyler manages to go to college, her sister gets a job flipping burgers, and at the age of eleven, Tara packs cashews, babysits and parlays that into musical theatre.

So far, so weird. But then brother Shawn becomes a violent and abusive bully, possibly exacerbated by those head injuries. When Tara defies her father and takes Shawn to hospital after one of the accidents, it’s a break-away act.

It’s not that they’re physical prisoners. They’ve been brainwashed and bullied, but not into complete submission, and Father has a few lucid moments.

Miraculously, Tara’s secret studies get her into Brigham Young University, even though her knowledge is so limited that when she sees Tyler reading Les Miserables and buys a copy for herself, Napoleon was no more real to her than Valjean. She’d heard of neither of them. Or the Holocaust. She’s from another planet where Diet Coke is the work of the Devil. She struggles. In many ways this is the most moving part of the book. What she learns at university makes it impossible to tolerate Shawn’s vile behaviour or her father’s madness… but who is she if not part of them?

The real tension in the book is Tara’s attempts to make sense of her mad family: maybe it was the head injuries that turned Shawn into a psychopath, maybe painkillers really were evil, maybe her father was right all along? Her refusal to become a hateful victim, her emotional intelligence, makes this a particularly riveting read.

Tara turns out to be a brilliant scholar, wins a scholarship to Cambridge, and when some members of the family validate her concerns about Shawn and about her father, she stops being ashamed… Not so tidy, of course. People recant, regress, make stuff up. Tara keeps trying to fix things, breaks down, and is finally saved, but not by her father’s God. She’s saved by education, which she latches onto like a drowning person to a raft. What didn’t kill her made her stronger, but it could easily have gone the other way. Which, given that the book hasn’t been published posthumously, is a foolish idea, but testament to how engrossing it is.

Educated: A Memoir by Tara Westover (Hutchinson, $38) is available at Unity Books.