How many hours you can and should work each week depends on the mode of thinking your job requires, writes Simon Hertnon.

Our national discussion about a four-day week has jumped out of first gear, thanks to last week’s Facebook live video by prime minister Jacinda Ardern.

In the video, which quickly garnered global media attention and more than half a million views, Ardern tells us, “I hear lots of people suggesting we should have a four-day workweek.”

Ardern had spent the day in Rotorua exploring ideas for boosting domestic tourism, and a four-day week would translate to a game-changing 50% increase in leisure days. No wonder she chose to “really encourage” us to think about shifting to a four-day week.

So, let’s think about it.

If a worker can produce the same or better value in four days than five, as the well-publicised four-day week trial by Perpetual Guardian proved, then persisting with a five-day week doesn’t make sense. More engaged and productive staff, less rush-hour congestion, more work-life flexibility, and, right now, more domestic tourism. What’s not to like?

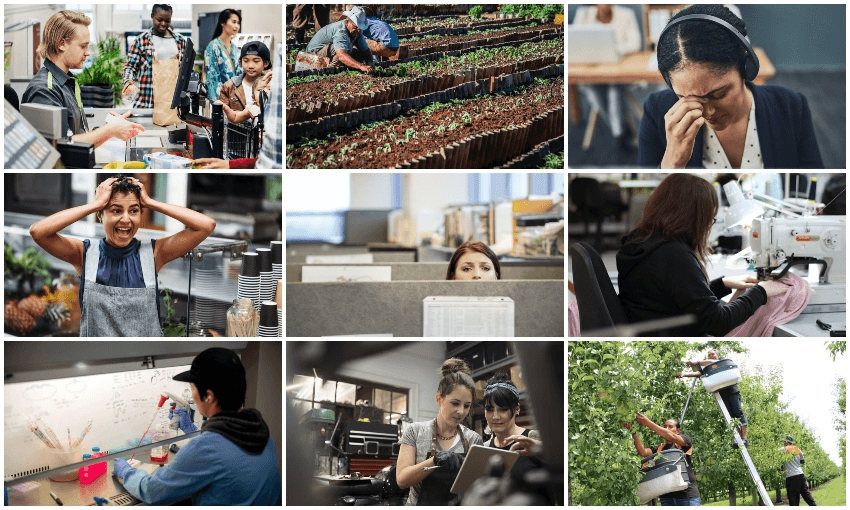

But isn’t this just hocus pocus? If it really is possible to achieve five days’ work in four, then why does anyone still work – or employ others to work – for five days? And if this workplace revolution doesn’t apply to a barista who simply can’t make five days of coffees in four days, then who else misses out?

Despite these sticky questions, I think a four-day week would be a tremendous step in the right direction – for some types of work. I think the missing piece of the puzzle is factoring in the amount of energy required to perform different types of work. Low-energy tasks can surely be sustained for five or six days, while four days might still be too much for tasks that exhaust workers in three or fewer days. I’ll come back to this idea.

I also think we need more discussion about the suitability of an eight-hour work day – a standard we formally adopted in 1938 – now that we live more complicated lives and use new technologies to perform new types of work.

But first let’s acknowledge the productivity question answered by Perpetual Guardian’s trial.

In February 2018, Perpetual Guardian’s then head of people and capability, Christine Brotherton, said, “If employees are engaged with their job and employer, they are more productive.” The company backed this up with multiple research papers, and I think we all innately understand this correlation. We all know the feeling of being able to achieve more when we enjoy our work and know others value our efforts.

Hungarian-American psychologist Mihály Csíkszentmihályi famously labelled this energy-giving state “flow”. I have also heard the Tauranga-based positive psychology practitioner, Melanie Weir, explain the phenomenon in terms of energy-sapping “away” responses – activities we want to avoid – and energy-giving “toward” responses – activities we embrace. Each response sparks activity in a different part of the brain. The effect is physiological, not just psychological.

It turns out that the same goes for what hasn’t been explained in the context of optimal work hours. I’m talking about the different energy costs of our two modes of thinking, which Nobel Prize winner Daniel Kahneman terms our “automatic system” (thinking fast) and our “effortful system” (thinking slow). Kahneman published his seminal book on the topic, Thinking, fast and slow, in 2011.

In a nutshell, the automatic system (which I think of as auto-pilot) is always on, leverages patterns, and uses very little energy. The effortful system (which I think of as deep thinking) fires up only when the automatic system encounters a situation it can’t deal with, such as problem solving, filling out a tax form, or even maintaining a faster-than-normal walking speed.

Put simply, thinking can be effortless or exhausting, just as walking can be effortless or exhausting. We can stroll for hours on end, but increase the pace and we soon become flushed, our heart rate increases, and we burn through energy in a way we cannot sustain.

It follows, then, that if your work regularly requires use of your effortful system, you won’t be able to work productively for as many hours as someone efficiently chugging along on auto-pilot. A manager juggling, say, reactive troubleshooting with proactive process improvement design should not, by my calculations, be working the same hours as a barista. Energy-sapping non-routine problem solving is chalk to the cheese of confidently repeating a set of mastered skills. And yet our norm remains to conform to a universal 40-hour (or 37.5-hour) workweek. It’s kind of crazy.

Aside from the pluses and minuses caused by varying levels of engagement, health and nourishment, human energy is a limited resource. So, yes, let’s discuss how we can best spend that precious energy.

As a knowledge worker who routinely solves energy-sapping non-routine problems, I don’t ask my clients to pay me for 40 hours each week when I know my energy will be spent in 20-30 hours. But likewise, I wouldn’t want anyone who hasn’t used up their energy in four days to reduce their workweek, or their wages.

Can employers not develop a sliding scale of optimal work hours? Surely that would make more sense.