Low income renters are facing a double whammy in the form of spiralling inflation and the looming threat of widespread job losses. Meanwhile, our biggest bank just chalked up record profits, writes Bernard Hickey.

This article was first published in Bernard Hickey’s newsletter The Kākā.

It was the best of times (again) for some. It was also the worst of times (again) for others. But the net result is the same. Covid’s winners are mostly winning again and Covid’s losers are being punished again for the sins of the winners.

Aotearoa’s ongoing and fastest monetary policy tightening in a generation is throwing up all sorts of questions about how monetary policy is operated in an economy that is now barely more than the world’s most expensive housing market with bits tacked on, and whether the Reserve Bank still has our societal agreement to do what it’s doing.

One thing we do know is that both the massive loosening in 2020 and early 2021 and now the fast tightening in 2022 has been the best of times for banks.

They are profiting now from all the extra mortgage lending they were encouraged to do by the Reserve Bank in 2020 and 2021, and from the higher interest rates it created in 2022, which have lifted their profit margins. They’re also profiting because the aggressive rescue in 2020 stopped bad debts from increasing.

That is crystal clear in the latest bank profit results.

Happy days for the big four, and especially the biggest one

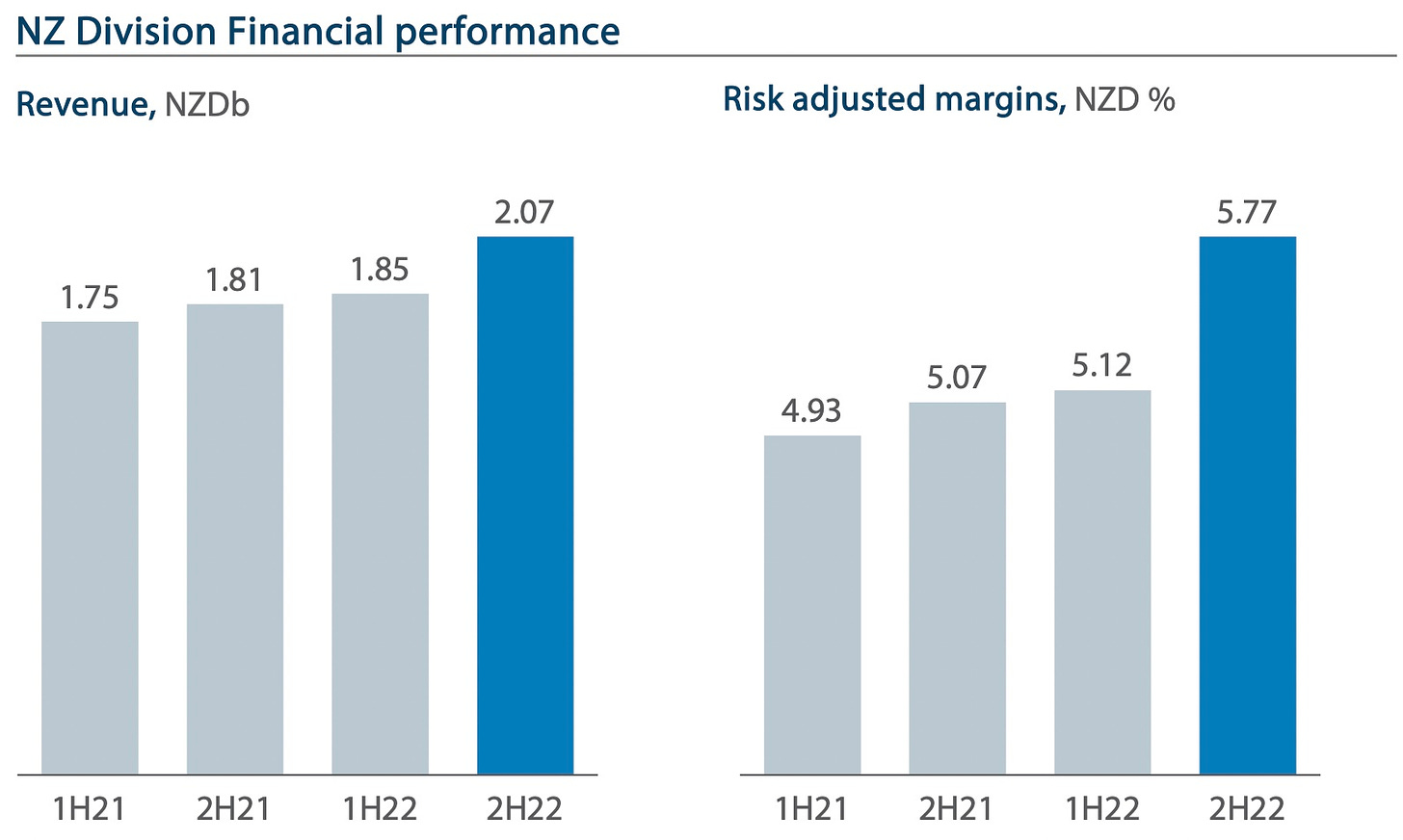

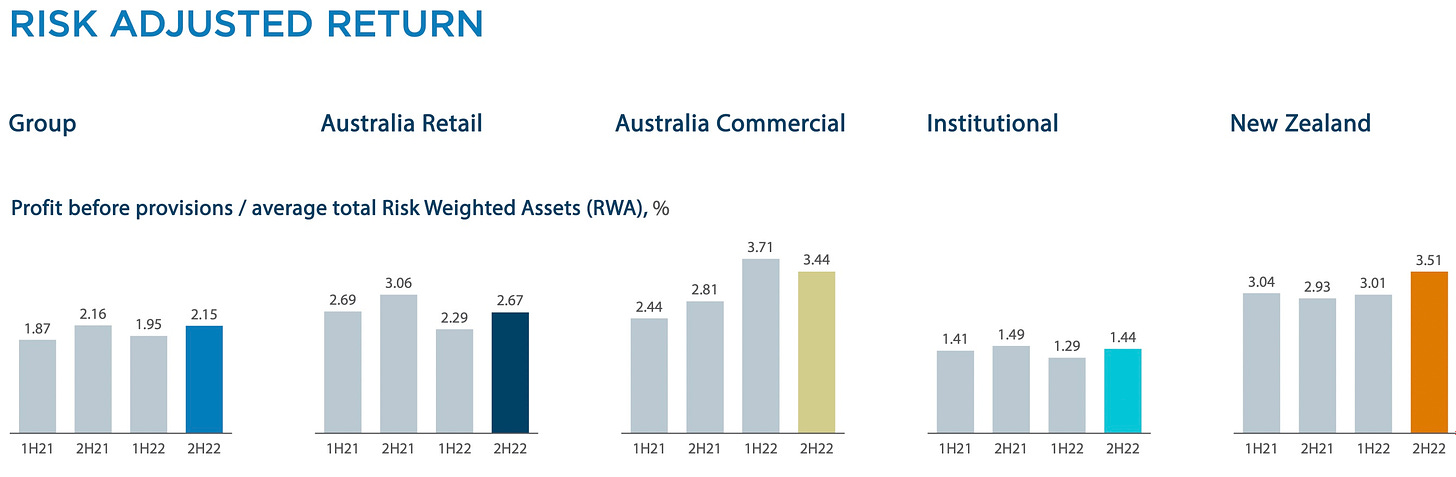

ANZ reported a record annual profit on Thursday of $2.3b, up 20% from a year ago. That figure is due to the higher interest rates the Reserve Bank is now cranking into the economy, and the extra $14b of home loans it made since Covid (over a time when ANZ lent less to businesses and farmers, and shed staff). Adjusted for the risk weightings of its loans and in outright terms, ANZ’s profit margins hit record highs and were higher than ANZ’s fellow divisions in Australia.

What the biggest bank does in a housing market with bits tacked on

ANZ’s strong performance as Aotearoa’s biggest bank is a reflection of how our economy is now completely dominated and driven by lending into the housing market, and how savers and bankers are incentivised to double down in the hunt for leveraged tax-free capital gains on land price appreciation – while avoiding investing in businesses, technology, training or infrastructure that doesn’t have access to that same leverage or those same tax advantages.

ANZ’s mortgage lending grew $8.8b in the last 18 months, while non-property business lending was flat and farm lending fell by $1.1b. The shift was even more pronounced in the last year, as shown in the chart below, with home lending rising by $6b to over $100b for the first time in the year to September 30, while business lending fell by $2b.

ANZ’s mortgage book has risen from 61% of total loans just before Covid to 74.9% by the end of September. Our largest bank effectively became the biggest weapon in the Reserve Bank’s “wealth effect” arsenal. In the process of rescuing Aotearoa’s economy from Covid, our independent central bank helped make 1.1m home-owning households $550b richer and has almost doubled the profits of our biggest banks to almost $7b per year.

Why bank profits rise when interest rates rise

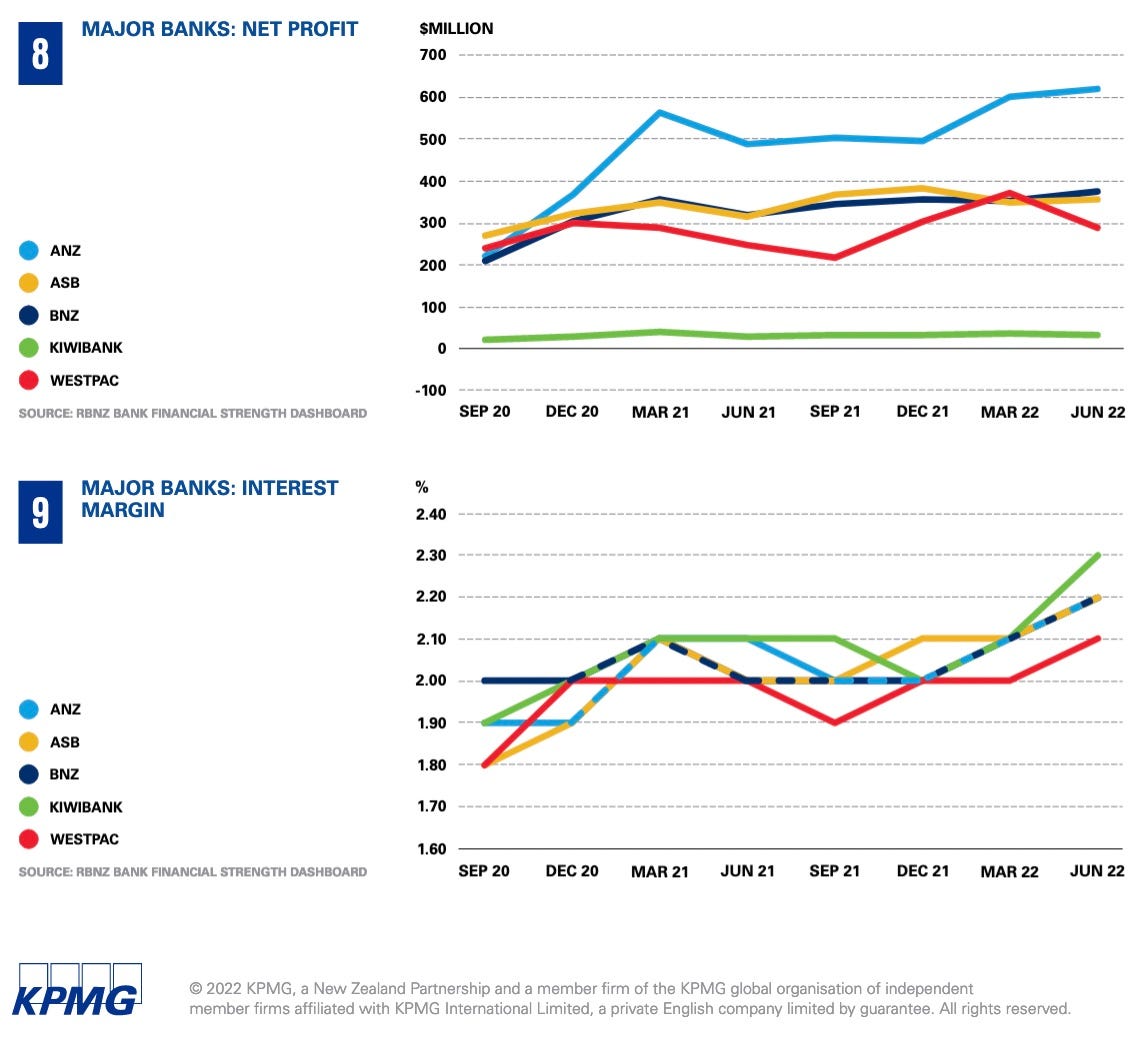

The key detail for any banker is that rising interest rates allow banks to increase their profit margins on lending. This is partly due to banks’ interest margins tending to rise when short-term interest rates are rising, as this June 2020 paper from the University of Waikato found.

KPMG’s industry-wide analysis from the June quarter, which included all the bank results, shows this too. The profit results are quarterly.

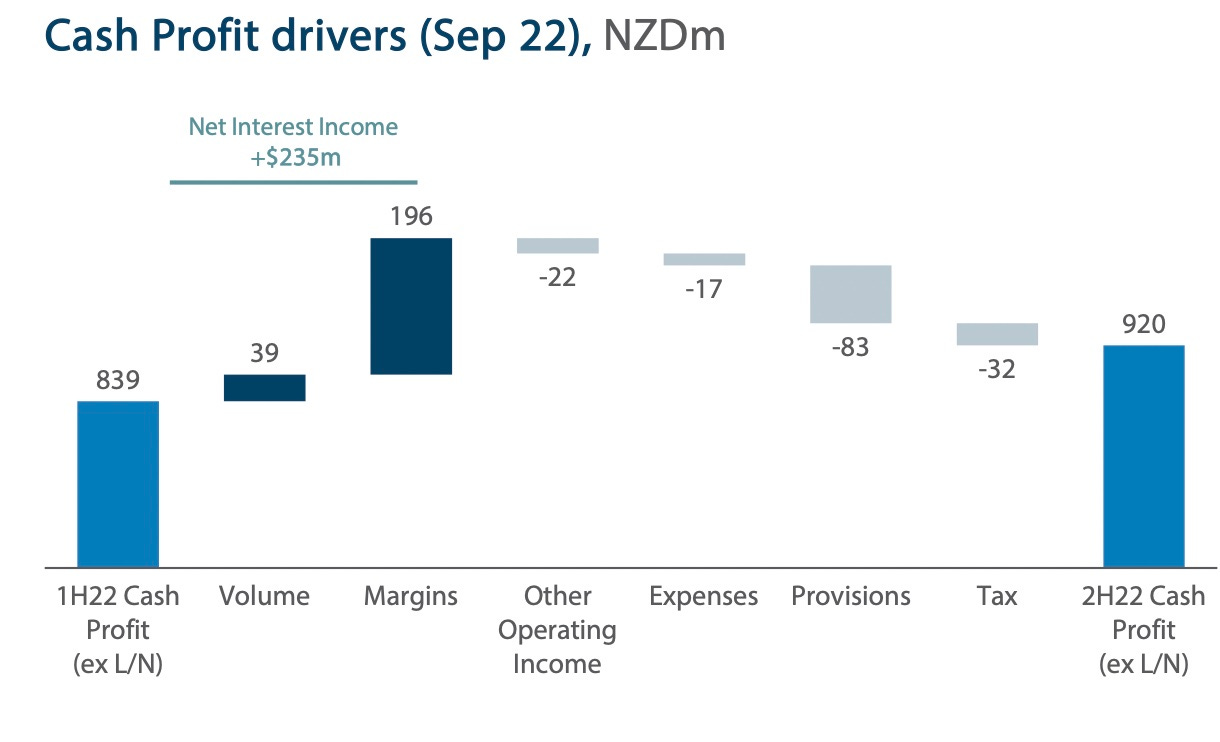

ANZ made the rising net interest margin clear in its explanation of its higher cash profits in the second half from the first half.

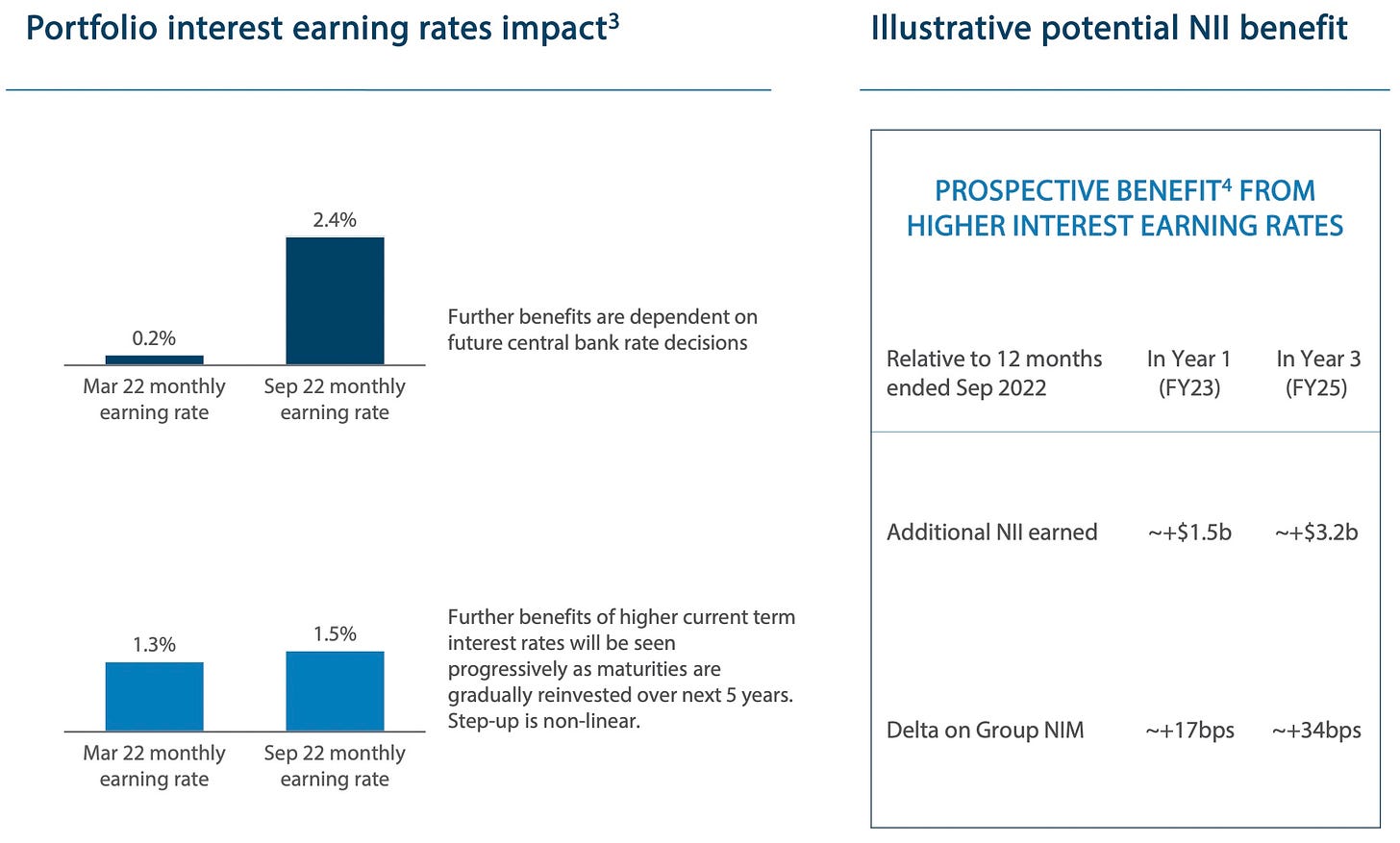

ANZ even included a slide in its group result showing how higher interest rates from monetary policy boost profits from net interest income (NII).

Now it’s time to fix the mistake. But who should pay?

It’s been a great year for the banks, but it’s been a bad year for the Reserve Bank itself, and for those low-income renters who saw prices of the things they spend all their disposable income on rise faster than their wages, including rents.

Asset owners, meanwhile, have seen their nominal asset values and the real value of their savings fall this year, but the hits to their spare disposable income and financial positions was relatively much less painful. They have buffers and savings to fall back on and they’re still sitting on net worth of $2.35t as at the end of June, up by $550b since Covid. Those who may have lost work and income during Covid and did not get the wage subsidy cash kept by their employers are on their own fighting consumer price inflation, without the buffers of savings or other assets.

The Reserve Bank has yet to acknowledge it publicly, but it over-stimulated the housing market and the economy in 2020 and 2021 by printing $55b to buy government bonds to lower longer-term mortgage rates and removed high LVR borrowing restrictions. That powered a 45% rise in house prices in 18 months and wiped out another generation’s hopes of home ownership. That monetary policy response, along with $20b worth of cash handouts to business owners that they banked, helped fire up inflation in 2021 and 2022 to over 7%.

To be fair, the Reserve Bank realised it had over-cooked the economy earlier than other central banks, stopping its money printing in mid-2021 and starting rate hikes in October 2021. It also reimposed and then toughened the LVR rules late last year, which finally put out the fire.

However, until now, it has defended its decisions and issued research, along with Treasury, that fudged on whether there was any inter-generational or inequality effect of its actions in 2020 and 2021.

Adrian Orr says unemployment will have to rise

The need to rectify the mistake was clear in a speech Reserve Bank governor Adrian Orr gave on Thursday, in which he detailed how more unemployment was needed.

He described how the central bank was actively looking to slow domestic spending to constrain inflation, noting that “New Zealand is relatively well positioned but inflation is still too high in an absolute sense”.

Orr pointed in particular to the need for higher unemployment and the risk of a financial markets accident further complicating the outlook. Here’s his summary (bolding mine)

“The list of near-term pressures goes something like: Returning to low inflation will, in the near-term, constrain employment growth and lead to a rise in unemployment. The actual extent of this trade-off remains unclear however, given the significant labour shortages globally and the very different means of employment being adopted post-Covid.

“Importantly, it is highly unlikely that we are at maximum sustainable employment if inflation is still high and variable.”

Orr has argued since the onset of Covid that the best thing the Reserve Bank could do was to take a “least regrets” approach to stimulating the economy that prioritised employment, given that preserving employment would do the most to reduce the harm to low-income earners.

However, inflation has hurt those in low-paid and precarious work the most, particularly those who are renters with little spare disposable income.

Follow Bernard Hickey’s When the Facts Change on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or your favourite podcast provider.

Inflation hits spare disposable income the hardest

It has been a very bad year for low-income workers and beneficiaries who rent. They were stung with much higher living costs relative to their incomes this year, having already missed out on the “wealth effect” created by the Reserve Bank to stimulate the economy in 2020 and 2021.

So how could the government and Reserve Bank rectify their economic mistakes in a different way, so that the beneficiaries are those hit hardest during Covid rather than those who did best?

The government has various tools at its disposable that would reduce inflation immediately and take pressure off both low-income renters and the Reserve Bank itself, which is stuck with the blunt instruments of the Official Cash Rate and reversing the “wealth effect” via the housing market. In my view, they could include a windfall profits tax on banks, as has been done in Australia, which would help pay for:

- Immediate cash benefit increases and Working For Families increases for both those working and out of work;

- Temporarily reducing the overall rate of GST or reducing GST on food;

- Removing or rebating GST on council rates, and the introduction of rates on Crown land (which the government currently does not pay), in exchange for rates decreases. Also rebating GST on building materials and building services to councils; and,

- Cutting public transport and other government fees that hit the poorest and youngest hardest, including drivers’ licence testing, student fees and doctors fees.

In summary

The Reserve Bank over-stimulated our economy in 2020 and 2021 by encouraging banks to pump extra debt into our economy (in particular our housing market with bits tacked on). Now it is having to increase interest rates to control the inflation it encouraged, which is in turn is inflating bank profits at a time when the Reserve Bank says more people will have to lose their jobs to solve the inflation problem. Meanwhile, the low-income renters who are bearing the most inflation pain, and got none of its asset-inflation gain, are set to bear the most pain again as the Reserve Bank tries to create more unemployment.

The Reserve Bank said more people would have to lose their jobs because it had no choice but to reduce the inflation it created and which made homeowners and banks hundreds of billions of dollars. It said this on the same day the single biggest beneficiary of the inflationary spike reported it’s making $6m in profit per day.

So why isn’t there a bank profits windfall tax to soften the blow to come of rising unemployment and higher living costs for those who don’t own homes or bank shares? And why isn’t the government using its own tools to reduce inflation from fees, taxes and charges, along with reducing living costs for the poorest?