All there is to know about the new Covid-19 variant detected in South Africa.

Editor’s note, 27 November: The headline on this article has been updated to reflect the variant’s newly-announced name.

At 8am local time on Thursday, November 25, researchers in South Africa met with government ministers to discuss a new Covid-19 variant they’d detected less than two days before. By 1pm that afternoon the minister of health Dr Joe Phaahia and the director of the Centre for Epidemic Response & Innovation (CERI) professor Tulio de Oliveira were fronting an emergency media briefing to tell the world about B.1.1.529. The World Health Organization’s technical experts will be meeting shortly to decide whether to give B.1.1.529 its own Greek letter. If they follow the current convention, by the time we wake tomorrow, it’s likely “nu” will be the new variant on the block. (Update, 27 November: WHO today announced the variant is to be named Omicron, after the 15th letter in the Greek alphabet. They’ve also added it straight to their Variant of Concern (VOC) list rather than just designated it a Variant of Interest (VOI). It took months for delta to be named a VOC.)

Where’s this new variant come from?

South Africa has recently emerged from its third deadly wave of Covid infections. The most recent wave was caused by the delta variant which had become the dominant strain there just like it has in many other countries. Over the last week or so, cases have begun growing exponentially again in one region in particular. In Gauteng Province, they’ve gone from having a test positivity rate – that’s the number of tests processed that are positive – from under 1% to over 30%. National daily cases have increased from 273 on November 16 to over 1,200 yesterday. Over 80% of those have been in Gauteng Provence and of the cases in Gauteng Province almost all of them now are this new variant.

At first, they thought the spike in cases was being driven by outbreaks at universities and from large gatherings. But with the effective R number jumping from less than 1 to about 2 in a matter of days, both the researchers and the government worried this could be the start of South Africa’s fourth wave.

How did they detect it?

South Africa has the Network for Genomic Surveillance – South Africa, where labs all around the country are sequencing Covid-19 virus samples to look out for any changes in the virus. On Tuesday, November 23, one of the labs in the network identified a new variant that gives a different PCR test result. This was how alpha, the first variant of concern, was identified in the UK.

Like alpha, a deletion in the variant’s genetic material causes a negative S gene PCR result when it should be positive. Because the PCR test looks for more than one gene from the virus, it’s a pattern that allows diagnostic labs to quickly identify the new variant rather than having to rely on whole genome sequencing. If a sample is negative for the S gene but positive for the other genes, then it’s this variant and not delta. It turns out there has been a big increase in recent days in the number of samples testing negative for the S gene. Worryingly, they aren’t just limited to samples coming from people in Gauteng Provence, suggesting the new variant is circulating more widely.

What’s so worrying about the new variant?

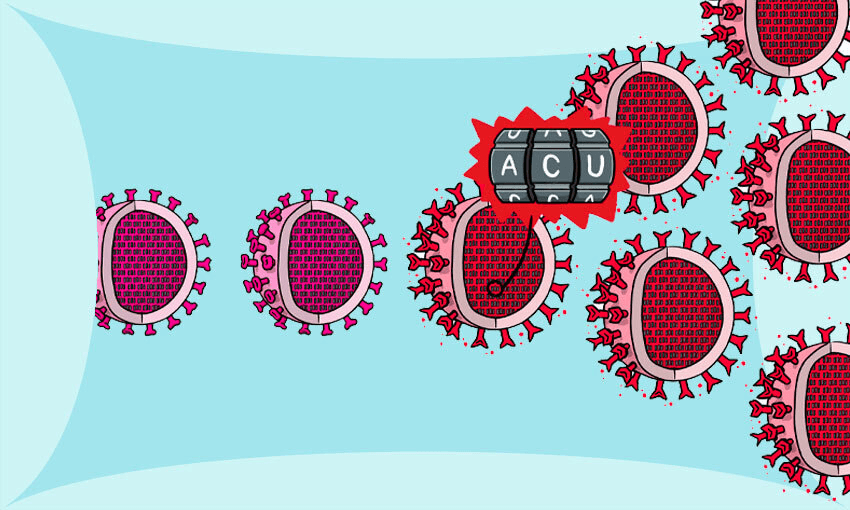

The reason they’ve gone public so quickly is to call global attention to what could be the variant to displace delta. Genome sequencing shows this variant contains an unusual constellation of over 50 genome mutations. Check out Toby Morris’s explainer below if you need a reminder of how these mutations arise.

While this variant’s sudden rise could just be due to what’s called the “founder effect” – which is when a mutant takes off not because it is more infectious, but because it is the one that people who are infectious happen to have – the genome sequencing is painting a more worrying picture.

Of its 50 or so mutations, some are already quite well-characterised as being involved in increasing the virus’s transmissibility and ability to evade the immune system. But many of the mutations have not been seen before. This begs the question, how will this combination of mutations impact on each other? Will they make this variant more transmissible than delta? Will the vaccines be less effective against it? Might it reinfect people who’ve already had Covid-19? Will it cause milder or more severe disease?

Researchers in South Africa have already started their experiments to find out, but on the basis of the mutations we do know about, there is real cause for concern. The delta variant has two mutations in its receptor binding domain that help make it more transmissible. This variant has 10. It also has more than 30 mutations in its spike protein. This is the protein all our current vaccines target, so that’s a real worry.

Professor de Oliveira ended the media briefing by saying he hoped he was wrong about this new variant, and it would turn out to not be worse than delta. I hope so too. But if we’ve learned anything this pandemic it’s that rapid action is crucial when it comes to Covid-19. South Africa will need resources to help it control and extinguish this new variant. The world needs to step up or we will all face the consequences.

The fact that this variant has emerged once again highlights how badly the world is handling the pandemic. While here in Aotearoa we are approaching nearly 70% of our total population fully vaccinated, in South Africa that number is less than 25%. They’ve had to start their own mRNA vaccine research and development programme because Pfizer and Moderna won’t increase production to meet the global need or share their technology so others can meet it instead.

Yet again we are reminded that none of us are safe until we are all safe. If you can spare a few dollars, consider making a donation to Unicef who are doing all they can to deliver Covid vaccines to those in need around the world.